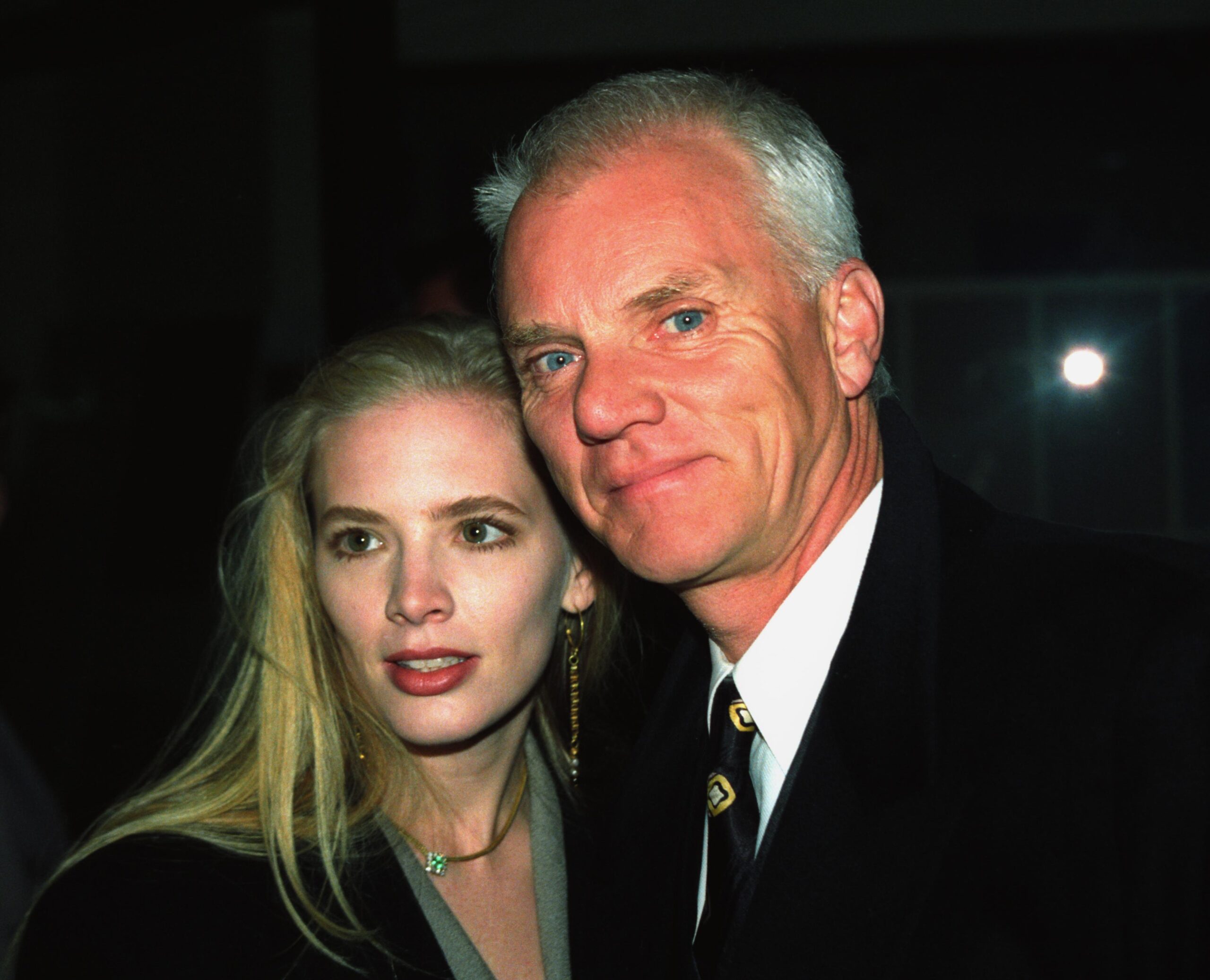

By Bart Sherkow - Shutterstock

Over the past year, I’ve used my increased time indoors to my advantage by catching up on a plethora of films that have been widely considered “classics.”

I still have a lot of movies left to watch, but I’ve seen enough to know what I do and don’t enjoy. I like sharp, heartfelt comedies. I like dramas that will make me cry. I like realistic love stories. I love coming-of-age movies with an edge. I enjoy surrealism, horror, and psychological thrillers — especially in a dystopian setting where critiques of the government or humanity as a whole are involved.

I didn’t know much about A Clockwork Orange before I recently decided to watch it for the first time, but from the small details I’d heard about it, I’d figured Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 “masterpiece” would be right up my alley.

Adapted from Anthony Burgess’ novel of the same name, A Clockwork Orange follows a young man named Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell), who lives in a near-future dystopian London. Alongside a small pack of like-minded companions he calls his “droogs,” Alex delights in overt violence, rape, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

(Warning: spoilers ahead, as well as descriptions of sexual assault.)

For the majority of my first watch of A Clockwork Orange, without knowing the ending, I was sold. I don’t need to explain why Kubrick’s direction is legendary across the board; there’s a reason why the “Kubrick Stare” never gets old.

He’s infamous for his perfectionism, and at the risk of exhausting (or even injuring) his actors, it pays off in the end. The set design is immaculate, especially considering the film was made on a fairly low budget.

A Clockwork Orange | Masterpiece Trailer | Warner Bros. Entertainmentwww.youtube.com

And speaking of budget, a good portion of it went to acquiring the rights to “Singin’ in the Rain,” which Malcolm McDowell improvised under Kubrick’s direction to make the first rape scene even more terrifying. From the synth score to the unnerving usages of well-known classical compositions, everything about A Clockwork Orange‘s artistry succeeds at lulling you into its unimaginably twisted universe.

In the decades since the release of A Clockwork Orange, its core meaning has been hotly debated. (I should disclose that I haven’t read the novel, although the movie stays pretty true to the original story.)

Is it a film about prison reform? About whether or not evilness can be cured? About the dangers of aversion therapy? About the sinister implications of drinking plain dairy milk?

Some of my favorite directors are those whose films can be interpreted a myriad of ways, such as David Lynch or Robert Altman. I typically welcome the challenge of a film ending that leaves me with more questions than answers. But the only question that A Clockwork Orange left me with was: “That’s it?”

After Alex undergoes the infamous Ludovico technique and is released from aversion therapy, not only is he repulsed by violence and sex, but he discovers that all his belongings have been sold and his parents have rented his childhood bedroom to another young man. He can’t even stand his favorite song, Beethoven’s Ninth, and he ends up nearly beaten to death by his former “droogs.”

Finally, Alex isn’t just watching some brutal videotapes with his eyes pried open for hours at a time; he has a first-hand experience at some of the terror he previously enacted on others, and the things that once brought him joy now drive him to contemplating suicide. The viewer is led to believe that Alex might actually be properly punished for his past nauseating lifestyle.

But any hope for a proper, ethical character arc for Alex is eradicated in the film’s final minutes. After his suicide attempt, he wakes up in the hospital, realizing that his aversion to violence and sex has waned. The Interior Minister who originally wanted to perform the Ludovico technique on Alex comes into his hospital room, apologizes, and offers him a job in return for support during the next election. Then, Alex narrates the film’s immortalized final line as he imagines himself having sex in front of an applauding crowd: “I was cured, all right!”

The general consensus among viewers seems to be that “cured,” in Alex’s case, refers to the relief he feels upon realizing that he’s returned to his original “ultra-violent” self; the pain he endured in futile attempts to change his ways were in vain. Either his wickedness is so deeply ingrained that it could never possibly leave him, or a change in lifestyle must be enacted by his own free will — not the product of a corrupted government rehabilitation system.

In the book’s final chapter — which Kubrick decided to omit from the movie — Alex, years later, decides to lead a fairly “normal” life and start a family. The story that Kubrick chooses to tell is that of inherent evil, in which one of the most immoral characters imaginable doesn’t receive adequate punishment for the harm he caused. Because, let’s be real, even a corneal injury is a slap on the wrist compared to brutal rape.

Some people are of the belief that rape should be left out of films, but I’m not one of those people. I believe art is a reflection of real life, and as long as rape happens in real life, it’s fair game to use as a plot device. But as a woman myself with her fair share of poor encounters with men, I find the way women are depicted in A Clockwork Orange to be unnecessarily gross. Aside from the minor roles of Alex’s mom and the doctor at Mr. Alexander’s house, women are treated as props throughout the film. And, of course, all the women Alex interacts with are white with “desirable” bodies.

We see violence against women frequently in film, particularly in horror and thriller movies. When depicted with adequate nuance and context, it can evoke the right emotions: For example, in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks prequel film, Fire Walk with Me, we see firsthand the emotional, psychological, and physical effects that years of sexual abuse has imposed on the protagonist, Laura Palmer. We see how this abuse has troubled her relationships with her family, her boyfriend, and her best friends, and how it eventually led her to dangerous habits as a coping mechanism.

A Clockwork Orange never grants its female characters the same empathy. Sure, we hear them scream, but the screenplay doesn’t allow us to understand the trauma that Alex inevitably inflicts on them. It can be argued that Kubrick does this so that we see the film from Alex’s strictly sociopathic point of view.

But, when everyone from David Bowie to Lady Gaga to real,actual children have replicated Alex DeLarge’s quintessential aesthetic, I have to worry that those who’ve identified with him in some way or another have missed the point of Anthony Burgess’ story entirely — whatever point that might be.

Of course, I say all this with the understanding that film is subjective, and what clicks for one person might not click for the next. Nothing I say is going to rob A Clockwork Orange from its status as a cinematic classic, and I don’t mean any ill will among those who enjoy the film.

But, in an era when we’re reevaluating much of cultural history, I write this with a final proposition: If we’ve gotten to a point where we can shun real-life Hollywood abusers, maybe it’s time to start rethinking the value we place on abusive fictional characters, too.