bl.UK

When Mary Went Missing: What’s True Crime?

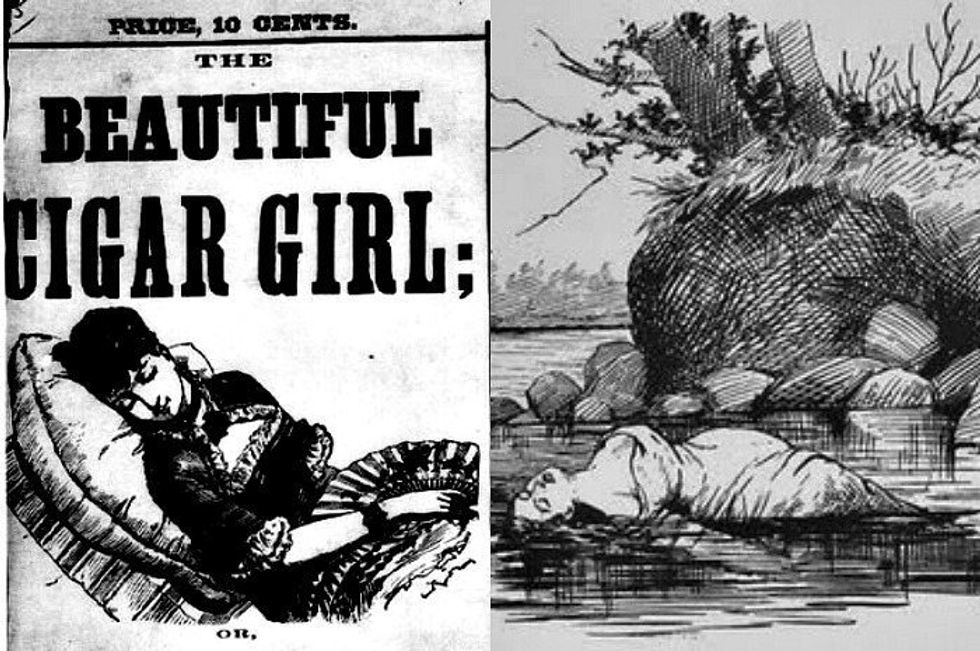

Mary Rogers was a 19-year-old working at a cigar store in downtown Manhattan, not far from her mother’s boarding house, when she didn’t come home one Sunday evening. No one realized that Mary was missing until Monday night. The teenager’s body was discovered in the Hudson River three days later. She’d been floating near Hoboken with clear signs of sexual assault, ligatures, and strangulation. The perpetrator was never found.

If you’re interested in finding out more about the case, you have nearly 180 years of investigation at your disposal. Mary Rogers’ murder took place in July 1841. The press coverage that followed set a precedent for high-profile crime stories. In particular, Edgar Allan Poe was living in obscurity in Philadelphia when the country was gripped by the story of an undetected predator having brutalized the young girl. When Poe published his fictionalized account of the murder, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” he cemented his own literary reputation and defined the American detective story.

Today, we see in the Mary Rogers story the familiar characteristics of true crime media: a victim (usually female) unanimously described as young, attractive, and innocent; the widespread threat of an unknown malefactor hiding among us; and an investigation rife with internal corruption and scandal, perpetuating a cycle of public speculation in the press.

Penny press coverage of Mary RogersAtlas Obscura

Penny press coverage of Mary RogersAtlas Obscura

In the last 5 to 10 years, the genre of true crime has surged in popularity, but what about the genre keeps audiences captive? From podcasts and Netflix documentaries to true crime books and television series, the last decade has fostered a cultural fascination with our most anarchic and nihilistic impulses toward criminality.

The transformative effects of new media have allowed true crime to catch the eye of Millennials, in particular. Streaming services have bolstered the genre with a deluge of content. When “podcast” was barely a 10-year-old word, This American Life producers released the first true crime podcast Serial in 2014. The series unpacks the multifaceted details of one true crime story per season; to date, it is the second most popular podcast in the U.S., out of more than 525,000 available streams.

Around the same time, Netflix started creating original content and reached binge-worthy status with crime docuseries like Making a Murderer in 2015, followed by hits like The Keepers (2017) and The Staircase (2018). On television, the Discovery channel rebranded its Investigation Discovery (ID) network in 2008 to almost exclusively feature shows recounting stories of kidnapping, stalking, and unsolved disappearances.

True crime podcastsMyAJC

True crime podcastsMyAJC

Our media choices are shaped by our environments, but we have agency as consumers to reciprocally shape not just media culture but collective social interests. Sociologically, media consumption is a form of social engagement through which we create and respond to public narratives. With Millennials coming of age with social media, their culture is heavily influenced by the power of public stories. Harvard historian Tim McCarthy argues that a moment’s zeitgeist is always shaped by the power of public narrative. Reflecting on the upheavals of the 20th century, he says, “All of these movement moments that changed hearts and minds and moved a nation in the direction of justice have been rooted in storytelling.”

In the last decade, the media has continued to demonstrate its ability to mobilize and empower individuals with sharper social awareness. The 2010s flooded screens with hashtag movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo, wherein media consumers rejected racial prejudice, spotlit institutional flaws, and demanded agency to change the status quo. If consuming media is a form of social participation, then increased consumer power is increased social empowerment.

Read the Omens: Crime-solving Media

As a genre, true crime queries the social factors that foster and punish humanity’s malefactors. Hosts and narrators examine the upbringing of victims and criminals for damaging social influences, question the quality of the investigation for prejudiced or sexist mishandling, and afterward opine on the integrity of our justice system. True crime audiences are situated in an ongoing conversation about what justice means in modern society, with their media choices acting as their response.

True crime author Harold Schecter expounds that “crime is inseparable from civilization—not an aberration but an integral and even necessary component of our lives.” As such, true crime isn’t intended to fetishize the perpetrator or the victim. Rather, the genre frames crime as an analysis of the contexts and sources of social violence. True crime audiences pin culpability not only on the criminal but on the society that created him.

Investigative historian Peter Vronsky interprets our preoccupation with killers as our instinctive concern over monsters—by their truest definition. Vronksy notes that the Latin root monstrum denotes “an omen or warning of the will of the gods.”

Vronsky’s own work builds from not one but three instances in which he crossed paths with various serial killers on otherwise unremarkable days, including bumping into Richard Cottingham, “The Times Square Torso Ripper,” in a midtown hotel lobby while the textbook “sexually sadistic serial murderer” still held the duffle bag containing two heads of his most recent victims.

“I experienced a monstrum,” Vronsky reflects, “one not so much bearing omens of the will of the gods, but of us, of ourselves, of our society. I came to see [serial killers] as monstrous, misshapen reflections in a distorted mirror to human civilization.”

Moreover, the participatory nature of true crime can occasionally result in a feedback loop between media, public interest, and ongoing investigations that can benefit the outcomes of cases. For example, Michelle McNamara, true crime fan-turned-author, helped stymied investigators finally pinpoint the killer of 13 women, Joseph James DeAngelo. McNamara’s independent sleuthing in her book I’ll Be Gone in the Dark shed light on DeAngelo as the California spree killer and rapist whom she re-named “The Golden State Killer.” Similarly, the producers of HBO’s documentary The Jinx may have solved the murders of at least two women after they recorded suspect Robert Durst confessing that he “killed them all, of course” after an interview.

As true crime media proliferates across digital streaming services, the genre serves as more than escapist entertainment, but a participatory study of society, our psyches, our fallibility, and our strength. We’re compelled to examine the worst of human impulses – like ” fairytales for grown-ups,” Schecter notes. “There’s something in our psyche where we have this need to tell stories about being pursued by monsters.”

Enter the Forest: Exposure and Empowerment

By consuming true crime, we subject our most fearsome monsters to close study and deconstruction. Criminology professor Scott Bonn finds that people exhibit “multifaceted and complex” fascination with true crime “because it triggers the most basic and powerful emotion in all of us—fear. As a source of popular culture entertainment, it allows us to experience fear and horror in a controlled environment where the threat is exciting but not real.”

Yet adrenaline from simulated danger can still activate our stress responses and give way to cathartic relief. Bonn distills the formula of true crime catharsis: “They initially take you into the forest and scare the hell out of you, but then by the end of it they bring you back out of the forest and you’re safe.” Utilizing true crime as a limited form of exposure therapy, consumers can exorcise their fears and even confront past traumas through their active and participatory engagement with the genre.

To wit, yes, consumers of true crime are drawn to lurid stories of murder, corruption, and betrayal— but also survival. Studies suggest that fear of falling victim to a crime can actually fuel a healthy desire to examine social violence. In an oft-cited 2010 study in Social Psychology and Personality Science, most true crime fans are women. Amanda Vicary, one of the psychologists who conducted the study, surmised, “One of the reasons women may enjoy crime books and television shows more than men is because women fear being crime victims a lot more than men do.”

On average, women are actually less likely to be victims of violent crimes than men (who are four times more likely to fall victim to homicide). Yet women are more vulnerable to specific types of violence. For instance, most male homicide victims are the result of drug or gang conflicts, while 70% of victims killed by a romantic partner are women.

The study found that women are particularly drawn to stories of victims escaping their attackers or surviving despite extraordinary odds. For example, Mary Vincent received much fan support in the true crime community after appearing in Lifetime network’s I Survived and being featured in Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark’s My Favorite Murder podcast. Vincent recounted surviving a depraved attack by serial killer Lawrence Singleton when she was hitchhiking in 1978. Singleton sexually assaulted 15 year-old Vincent and severed both of her arms before abandoning her in the wild. Since her remarkable survival, the thriving wife, mother, and artist advocates for teenage assault victims through the Mary Vincent Foundation.

Vicary adds that women extract “potential life-saving knowledge” from true crime stories like Vincent’s. In fact, engaging with true crime can transmute anxieties over potential victimhood into sharpened awareness for risk assessment and survival strategies. Vicary notes, “By learning about murders—who is more likely to be a murderer, how do these crimes happen, who are the victims, etc.—people are also learning about ways to prevent becoming a victim themselves.”

True Crime Cases, March 1962Pinterest

True Crime Cases, March 1962Pinterest

To that end, true crime audiences respond to social violence by educating themselves about personal safety, coping strategies, and the justice system. Additionally, practicing empathy for the victims—and sometimes even the perpetrators—reframes would-be gratuitous crime stories as tales of survival and empowerment. Author Megan Abbott praises the uplifting effect of crime consumption in her LA Times article, “Why Do We—Women in Particular—Love True Crime Books?” She writes, “It begins as a tale of female victimhood, but in the end, it becomes a testament to female intuition and survivor instincts. The script is flipped, and women are weaponized.”

Modernity’s Monsters: True Crime for Change

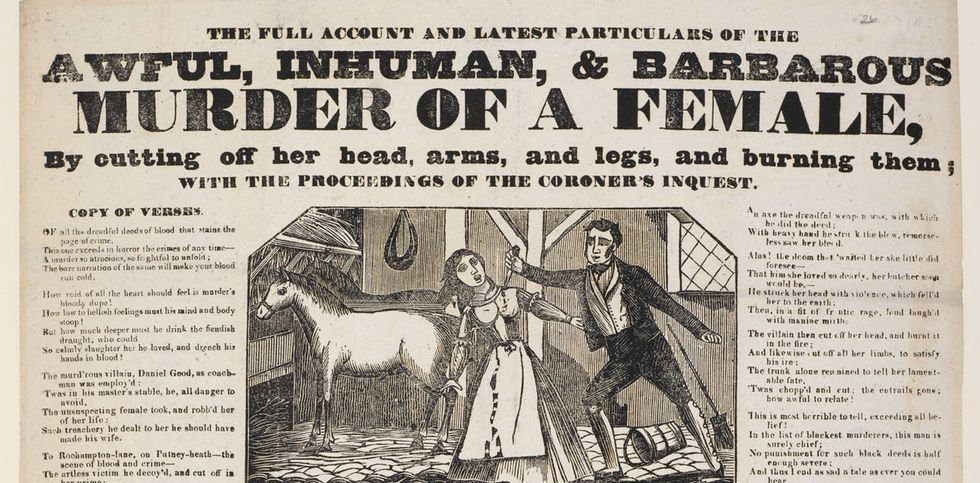

Of course, public fascination with death is far from a modern phenomenon. The thrill-seeking impulse to experience secondhand violence has existed from ancient Romans’ bloodlust for gladiatorial sport to Victorians flocking to crime scenes to witness the blood smears, steal souvenirs from victims’ homes, or purchase broadside pamphlets abridging all but the most dramatic and gruesome details. (Such publications were widely available outside crime scenes in 1850s England prior to the rise of newspapers).

April 3, 1852, broadside pamphlet on the crimes of Daniel GoodDocumentary Tube

April 3, 1852, broadside pamphlet on the crimes of Daniel GoodDocumentary Tube

Crime stories have always captured reality like negative photographs exposing shadow and delineating light. Schecter proposes, “Criminals can only fulfill their social function if the rest of the world knows exactly what outrages they have committed and how they have been punished—which is to say that what the public really needs and wants is to hear the whole shocking story.” If so, then criminality serves the “social function” of reflecting our values, our vulnerabilities, and our capacities to adapt—to forgive, even.

Now, more than ever, we understand monsters as omens—not just warnings but calls for social change.

POP⚡DUST | Read More…

Tracy Chapman Sues Nicki Minaj

Selena Gomez’s Sweat is Worth More Than You’ll Ever Be

Selma Blair Spotlights MS Disease’s Difficult Diagnosis

- The New True Crime ›

- Why women are fueling the popularity of true crime podcasts – CBS … ›

- How True Crime Helps Us Process Our Fear – Trust Issues – Medium ›

- Being A Woman Is Terrifying, So Why Does True Crime Make Me … ›

- True Crime Confidential – Multichannel ›

- Snapchat Debuts ‘True Crime/Uncovered’ From Condé Nast … ›

- Why Are Women Obsessed With True Crime? – The Hairpin ›

- Why young women are the biggest true crime buffs – Business Insider ›

- Podcast Audiences: Why Are Women Such Big Fans of True Crime … ›