CULTURE

On Taylor Swift’s “Eating Disorder”: What the Media Got Wrong About “Miss Americana”

27 Jan, 20

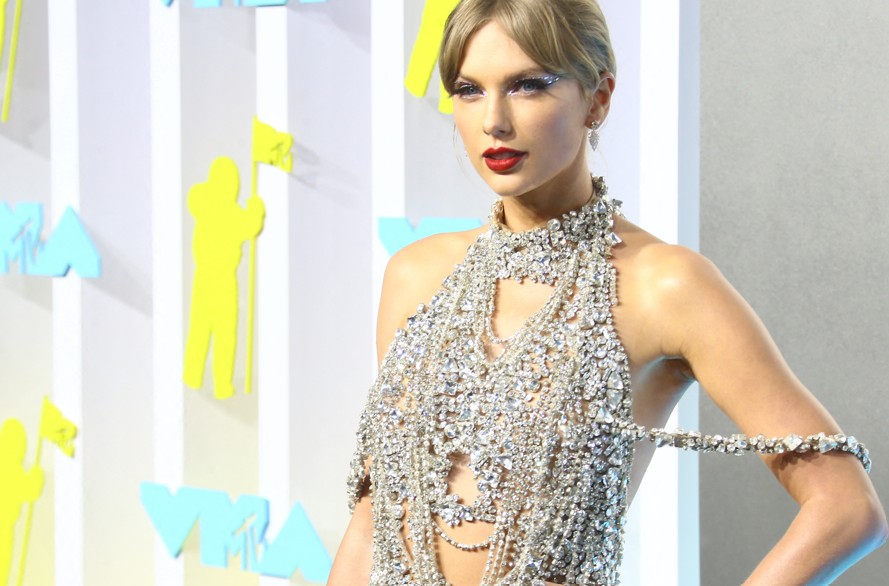

Taylor Swift at the Toronto International Film Festival

Photo by Evan Agostini (Shutterstock)

Somewhere between debuting as a 16-year-old, wholesome, big-haired country singer and becoming the world’s top-earning artist and the Artist of the Decade at age 30, Taylor Swift grew up–in the process of doing so, she sort of divided America.

In a string of self-reinventions, her bouncing blond curls and dreamy love songs transformed into blood red lipstick and vengeful heartbreak, before most recently turning into glitter hearts and pastel rainbows. To her admirers (85.5 million of which follow her on Twitter, with 125 million more on Instagram), these seemingly contradictory stages of her career embody the flirty, furious experience of coming of age in America. Strident critics, however, attack her whole brand as poison bubble gum, calling her initial refusal to comment on politics an attempt to profit from her former (unwitting) status as an alt-right icon and deriding her as a shallow white feminist who defines herself by playing the victim. They don’t like her singing, either.

Now we’ve met a new iteration of Taylor Swift, with her Netflix documentary, Miss Americana, billed as an uncharacteristically revealing look behind her highly cultivated image. Helmed by Emmy Award-winning director Lana Wilson, the documentary includes Swift’s introspective voiceovers, including an intimate segment in which she opens up about her unhealthy relationships with food, weight, and beauty standards in a society that expected her to be a “polite young lady.”

Praise and Punishment: The American Dream

After Miss Americana premiered at Sundance on Thursday, it seems every news outlet jumped at the chance to commend the singer for “Overcoming Struggle with Eating Disorder.” Among Swift’s revealing commentary, she shares “how unhealthy that’s been for me—my relationship with food and all that over the years.” Swift says in the documentary that she’d “go into a real shame/hate spiral” when it came to her body image and eating patterns. She says, “It’s not good for me to see pictures of myself every day… [I]t’s only happened a few times, and I’m not in any way proud of it, [but] whether it’s a picture of me where I feel like I looked like my tummy was too big or someone said that I looked pregnant… That’ll trigger me to just starve a little bit—just stop eating.”

She elaborated in an exclusive interview with Variety, who ran the aforementioned headline: “I remember how, when I was 18, that was the first time I was on the cover of a magazine. And the headline was like ‘Pregnant at 18?’ And it was because I had worn something that made my lower stomach look not flat. So I just registered that as a punishment.” And yet, in dressing rooms for photo shoots, Swift would be praised for her slenderness. “[S]omebody who worked at a magazine would say, ‘Oh, wow, this is so amazing that you can fit into the sample sizes. Usually we have to make alterations to the dresses, but we can take them right off the runway and put them on you!’ And I looked at that as a pat on the head. You register that enough times, and you just start to accommodate everything towards praise and punishment, including your own body.”

Swift goes on to describe some of the distorted thinking patterns and preoccupations with food and weight that are, indeed, common warning signs of an eating disorder. During her 1989 album tour in 2015, her behaviors affected her stamina to perform. “I thought that I was supposed to feel like I was going to pass out at the end of a show, or in the middle of it,” she says in Miss Americana. She’d keep lists of everything she ate, exercise excessively, and, perhaps most insidiously, she found herself locked in rigid, dichotomous thought patterns whereby everything was labeled as either “good” or “bad”–including her. Swift says, “My relationship with food was exactly the same psychology that I applied to everything else in my life: If I was given a pat on the head, I registered that as good. If I was given a punishment, I registered that as bad.”

Diet Culture, the DSM-5, and Disordered Eating

Wilson, a director known for her work on fraught social issues like abortion or suicide, seemed moved by Swift’s candor, saying, “That’s one of my favorite sequences of the film. I was surprised, of course. But I love how she’s kind of thinking out loud about it. And every woman will see themselves in that sequence. I just have no doubt.” Wilson’s remarks ring all too true, considering that at least 30 million Americans have an eating disorder, at least one person dies as a direct result of eating disorder complications every 62 minutes, and eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD).

However, there’s a difference between an “eating disorder” and a general pattern of disordered eating. Based on all reports of her commentary, Swift’s experiences are best described as the latter, despite widespread press coverage lauding her honesty about her “eating disorder” (the only exception found, as of this writing, was Vice, who exclusively used “history of disordered eating” to describe Swift’s struggles).

The painful experience of a clinical “eating disorder” lies at the end of a broad spectrum of unhealthy eating patterns; disordered eating can take many forms. As Cleveland Clinic points out, “Disordered eating covers a broad range of conditions, including anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder. But there’s a much larger percentage of people (5 to 20%) who struggle with symptoms that do not meet the full criteria of a problematic eating pattern.” In other words, all individuals with “eating disorders” have disordered eating, but not all individuals with disordered eating have (or will develop) an “eating disorder.” The distinction, according to mental health professionals, hinges on the “level of obsession around eating disorder thoughts and behaviors” and the degree to which disordered eating impairs one’s ability to function in their daily lives. Or, as Dr. Carrie Gottlieb, a clinical psychologist who specializes in the treatment of eating disorders, says, “It is all about degree. An individual with disordered eating is often engaged in some of the same behavior as those with eating disorders but at a lesser frequency or lower level of severity.”

While Taylor Swift’s struggles may not have escalated into a lifelong, full-blown eating disorder (“It’s only happened a few times, and I’m not in any way proud of it”), they are no less valid. Cleveland Clinic asserts, “Like full-blown eating disorders, these below-threshold conditions can lead to significant distress, impacting a person’s overall health and quality of life.” All forms of disordered eating can have life-changing physical and emotional effects, ranging from heart damage and GI complications to depression, self-image distortions, and social isolation, among many others.

The Media Says It’s Feminine to Starve

But in order to provide appropriate support, compassion, and resources–precise language matters. Dismissing the difference between an “eating disorder” and disordered eating is lazy, and it has consequences for individuals exhibiting those behaviors, as well as our cultural understanding of their causes. Dr. Holmes, a professor at the University of East Anglia and critic of pop culture media, calls attention to the “long-standing concern about the adequacy of media reporting, and the implications this has for public understandings of EDs [eating disorders].” She critiques, “A number of scholars have noted how such portrayals [of food restriction] are deeply contradictory in their bid to both pathologise and glamourise self-starvation.”

In other words, freely labeling every pattern of unhealthy eating as an “eating disorder” not only trivializes the mental illness; it pathologizes those unhealthy behaviors that are not cemented by the same “biological, psychological, and social factors” that underlie eating disorders. Ultimately, this just makes it more difficult to understand and articulate the underlying causes, not to mention ask for help.

From extreme dieting to rejecting food as a way to reject one’s own body or society’s oppressive control over one’s body, there are numerous, deep-seated reasons why people restrict food. Dr. Holmes notes, “Disordered eating may not necessarily be motivated by the drive for pursuit of thinness or any ‘distortion’ of body image, but rather by wider experiences’ of gender expectations and pressures.” Aside from the fact that disordered eating is still widely represented as only affecting women (despite the fact that men account for at least 25% of disordered eating cases, and untold greater numbers identify outside the gender binary), disordered eating is often gendered as a feminine activity. Dr. Holmes writes, “Thinness and starvation are seen as rendering femininity small, weak and fragile, whilst the emaciated body has been read as a form of corporeal resistance – the rejection of feminine subjectivity through an escape into a childlike, boyish or ‘degendered’ form.”

Media has an ugly habit of warping restrictive eating to seem delicate rather than violent, like cracked porcelain rather than rubble–and that makes for good headlines. In a twisted way, disordered eating has been depicted as a sexy fall from grace that manages to condemn all the ills of objectified femininity while still profiting from it. So it’s understandable why the press would jump to write about Taylor Swift, once America’s ingenue, having suffered from an eating disorder.

But when Swift says in the opening of Miss Americana that she always wanted to “be thought of as good,” she speaks to the fact that disordered eating is never about food; it’s a symptom of being unsettled in one’s body, or disoriented about one’s place in the world. For Swift, it was a coping mechanism for the high pressures of the entertainment industry as a reward system and measurement of her own value, as both a woman and an entertainer. Generally speaking, equating one’s self-worth with one’s body’s size is always an attempt to cope with overwhelming circumstances, a way to channel mental distress into a seemingly productive action, a way to assert stable control over the self in a chaotic world.

That’s not to say social pressure and media’s propagation of a thin body type as the ideal form isn’t a contributing factor. Swift told Variety, “[W]omen are held to such a ridiculous standard of beauty. We’re seeing so much on social media that makes us feel like we are less than, or we’re not what we should be, that you kind of need a mantra to repeat in your head when you start to have harmful or unhealthy thoughts.”

At least the media coverage of Swift’s struggles with food created a triumphant story of self-acceptance. She told Variety that she no longer cares about “the fact that I’m a size [X] instead of a size [X].” She’s built a healthier relationship with food, partially thanks to other prominent women who speak out against toxic diet culture and spread messages of self-acceptance, like Jameela Jamil and Brené Brown. She says, “The way [Jamil] speaks is like lyrics, and it gets stuck in my head and it calms me down,” while Brown helped her realize, “‘It’s ridiculous to say “I don’t care what anyone thinks about me,” because that’s not possible. But you can decide whose opinions matter more and whose opinions you put more weight on.'” Finally, she concludes, “I don’t expect anyone with a pop career to learn how to do that within the first 10 years. But I am actually really happy. Because I pick and choose now, for the most part, what I care deeply about. And I think that’s made a huge difference.”

Regardless of how one feels about Swift, her remarks highlight media’s continued misrepresentation of eating disorders and our cultural misunderstanding of them. But if it were framed differently, Taylor Swift’s “history of disordered eating” could have a greater impact on more individuals than Lana Wilson or Variety or perhaps even Swift herself realizes. Remember that while an estimated 30 million people (9% of the U.S.) have an eating disorder, up to 65 million (20%) struggle with disordered eating. Many of those people live in a state of tension between sensing that their behaviors are unhealthy and feeling validated by diet culture’s positive reinforcement–from feeling rewarded that their behaviors are “good.” In that sense, who better to speak to those millions than a pop icon who’s always embodied contradictions? If nothing else, Taylor Swift embodies the contradictory messages of growing up (especially as a woman) in America: Be independent but ask for approval, be outspoken but only when asked, be good even if it hurts.

- Miss Americana | Netflix Official Site ›

- Taylor Swift speaks out on overcoming eating disorder in ‘Miss … ›

- Taylor Swift reveals eating disorder in new Netflix documentary | Fox … ›

- Taylor Swift Opens Up About Struggle With Eating Disorder … ›

- Taylor Swift details past eating disorder in ‘Miss Americana’ – Los … ›

- Taylor Swift discloses fight with eating disorder in new documentary … ›

- Taylor Swift shares she struggled with an eating disorder – CNN ›