Music

Phoebe Bridgers’ “Kyoto” and the Spectacle of Japan in the White Imagination

21 May, 21

Phoebe Bridgers Kyoto

Slouching in front of a lo-fi green screen image of a temple in Japan, a platinum-blonde white woman in a skeleton suit sings the opening lines to her song: “Day off in Kyoto / Got bored at the temple / Looked around at the 7-11.”

A dear friend of mine once described “Kyoto” by Phoebe Bridgers as a “millennial indie song remake” of Sofia Coppola’s 2003 film entitled Lost in Translation. A “hallmark of American indie cinema” that portrays Japan through the white gaze and imagination, Lost in Translation is essentially about two white people (played by Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson) who fortuitously cross paths and navigate their feelings together in Tokyo. Despite the film’s non-American setting and backdrop, the entire film is centered around the pair’s (white, American) feelings and interiority.

Perhaps one day, Scarlett Johansson will be cast as Phoebe Bridgers in a post-pandemic reboot of the film entitled Dreaming Through Tokyo Skies. In a 5-star review of Lost in Translation, a Letterboxd user writes, “God I love this film so much i can’t put it into words. 100/100. Can they pls make a Phoebe Bridgers Kyoto mashup – ‘day out in Kyoto, got lost in the temple’ imagine this overlayed with Scar Jo wandering around!”

Like Lost in Translation, both the song and music video for “Kyoto” serve as manifestations of white ignorance and an extreme lack of cultural awareness. Unfortunately, white ignorance and cultural insensitivity have been historically ingrained into the collective consciousness of white America’s indie and alternative music scene.

For some strange reason, white indie musicians have always been keen to incorporate elements of Japanese culture into their work. Perhaps the worst example of this would be a body of work as heinous as Weezer’s 1996 album Pinkerton, featuring songs that blatantly fetishize and objectify Asian women such as “Across the Sea” and “Butterfly.”

The album references the white male character Pinkerton in Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, which first premiered in Milan in 1904. The songs in Pinkerton consist of lyrics such as, “You are 18-year-old girl who live in small city of Japan” and, “Maybe I need fantasy / Life of chasing butterfly.”

Another example of (less outwardly racist, but still questionable) Japan-obsessed indie music that comes to mind is the 2012 song by Chairlift entitled “I Belong in Your Arms.” The song was not only written from the perspective of a “crush-obsessed” Japanese schoolgirl but also released together with a “Japanese version” single and music video in order to “reduce [the song] to pure music and fantasy.” Although the song itself has nothing to do with Japan or Japanese culture, the karaoke-style music video features a white singer performing the song entirely in Japanese, alongside Japanese subtitles.

Similarly, upon taking a closer look at the lyrics and music video for “Kyoto,” it becomes overwhelmingly clear that Japan and elements of Japanese culture are nothing more than ornamental backdrops for Bridgers and her personal strife. Since its release in April 2020, “Kyoto” has garnered over 38 million streams on Spotify alone. The song has been Grammy-nominated for “Best Rock Song” and “Best Rock Performance,” and Bridgers herself has been nominated for “Best New Artist” and “Best Alternative Music Album” for her 2020 sophomore album, Punisher.

Despite the song’s growing public attention and critical acclaim since its release in April 2020, there have been very minimal critiques of its blatant use of Japan as a mere backdrop for the white experience. Here, we will unpack the overwhelmingly whitewashed role that Japan plays in the song lyrics and music video for “Kyoto.”

The “Kyoto” Music Video: A White Woman in Pseudo-Japan

In an essay entitled “Why White Queers Love Japan,” astrologer Alice Sparkly Kat deconstructs the psychology behind the pseudo-Japan that exists in the white queer imagination. Sparkly Kat suggests that “the Japan that white queers love so much is really a Japan of images and objects without any Japanese people.”

Similarly, the pseudo-Japan in “Kyoto” has very little to do with a real place that exists outside of Bridgers’s imagination. As is typical of art by white creators that features white people exploring nonwhite cultures, the Japan in “Kyoto” is only rendered meaningful due to its proximity to white thoughts, white feelings, and white introspection.

Throughout the “Kyoto” music video, which was tellingly directed by a white woman, we see Bridgers in a skeleton suit as she poses in front of various green screen stock images of Japan. While singing the first line of the song and standing in front of two Japanese temples, she manages to mispronounce and incorrectly articulate the word “Kyoto,” saying it in three syllables instead of two.

Then, as she sings about how her band “took the speed train,” we see her standing in front of a walkway featuring the bright orange torii gates at the Fushimi Inari Taisha shrine in Kyoto. The shrine itself was built in 1499 to honor Inari, the Shinto god of rice and prosperity. In Bridgers’s music video, however, the ancient and sacred shrine is reduced to an ornamental backdrop for the adventures and musings of white people as they travel and enjoy themselves in foreign lands.

Visions of Japan From the White American Imagination

The problematic nature of Bridgers’ depiction of Japan in “Kyoto” is perfectly encapsulated by what Sparkly Kat describes in their essay as “a pseudo-Japan that reflects American elements back to itself.” Sparkly Kat also cites the words of anime theorist Hiroki Azuma, who argues that the Japan that exists in the white imagination is in fact “a pseudo-Japan manufactured from U.S.-produced material.”

In an almost direct mirroring of the white pseudo-Japan that Azuma describes, Bridgers’s depiction of Japan in the first verse of “Kyoto” only contains elements of Japan that are familiar and prominent within American culture and history, such as the 7-11 corporation of convenience stores, the speed train, the arcade, and the payphone.

In the first verse of “Kyoto,” Bridgers sings, “You called me from a payphone / They still got payphones / It costs a dollar a minute.” Unfortunately, Bridgers herself admits that she did not fact-check these lyrics to accurately depict the Japan that exists outside of her white imagination. In a Rolling Stone interview, when asked about the payphone line, Bridgers proudly confesses that she “totally made that up” and has “never even Googled it.”

Bridgers’s lyrics about payphones in “Kyoto” subtly suggest that Japan is a backward country that “still” uses a costly and outdated technology. The only time Bridgers references a non-American element of Japanese culture is to say that she “got bored at the temple,” which in turn implies that ancient Japanese places of worship are incapable of fulfilling her need for entertainment as a white American tourist.

Japan makes its final appearance in the second chorus of “Kyoto” when Bridgers sings, “Dreaming through Tokyo skies.” Here, the word “Tokyo” is once more mispronounced and incorrectly articulated in three syllables.

The remainder of the song is centered around Bridgers’ brother and father, and the lyrics are filled with purely American imagery and references: Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, the suburbs, and the Goodwill chain of thrift stores. Despite the entire song taking its name from a Japanese city that Bridgers seems to have visited only once as a white American tourist, the second half of the lyrics take place in an all-American landscape, which conveniently acts as an alternate non-ethnic backdrop for Bridgers and her white experiences.

White People at the Foreground of Japanese Imagery

The anime-filled image that appears on the screen from 0:17 to 0:18 as Bridgers sings the phrase “went to the arcade” is undoubtedly one of the most questionable images in the entire music video.

As soon as Bridgers utters the word “arcade,” we see her standing in front of a row of three pastel pink arcade machines, each decorated with images of anime girls. Bridgers stands directly in front of an arcade machine decorated with an image of a white blonde anime girl, which further reinforces the dissociative presence of whiteness within the pseudo-Japan that Bridgers inhabits in her music video.

In “Why White Queers Love Japan,” Sparkly Kat writes, “The cultural disassociativeness of anime implies that gender can exist separately from ethnicity, nationalism, and socio-economics. Because white people find comfort in seeing themselves in a neutral and blank state rather than a racialized state, they can enjoy the culturally dissociative space offered by anime.”

Cultural dissociation is indeed heavily present throughout the “Kyoto” song lyrics and music video, given that white people are the most prominent and hyper-visible human figures in the foreground of unmistakably Japanese backdrops and settings.

In the “Kyoto” music video, a total of three other white people (apparently Bridgers’s friends and bandmates) are at the foreground of images containing Japanese iconography. During an instrumental solo that takes place towards the middle of the song, we see a white man in pink sunglasses standing in front of a green-screen image of Mount Fuji. Then, the video cuts to more images of Bridgers standing in front of Japanese temples while singing about a distinctly American landscape.

As soon as Bridgers utters the word “chemtrails,” we briefly see another white woman standing in front of indoor shoji screens. Later on, this same woman appears again in front of a path of sacred torii gates.

The culturally dissociative relationship between the song lyrics and the images on screen persists throughout the rest of the music video. While Bridgers sings about her white American experiences, viewers are immersed and situated within Japanese settings that are dominated by unmistakably white bodies.

The Problem With White Americans Referencing Godzilla

Regardless of whether or not Bridgers intended to appropriate Japanese culture and imagery in her song and music video, one can’t help but wonder: What might serve as the subconscious motivation for a white woman and her all-white creative team to juxtapose Japanese images against white bodies, white feelings, and white experiences? Why do white people constantly utilize Japanese imagery as a backdrop to their own unrelated stories?

As Sparkly Kat writes, “Part of it is the power relation. Because of the colonial relation between the United States and Japan, white queers are able to see themselves as creators and authors who use and remix Japanese imagery in a way that they cannot with western pop material.”

As if the presence of multiple white people in Bridgers’s pseudo-Japan was not already enough, there is an almost caricatural section of the music video in which Bridgers saves her white friends and bandmates from Godzilla.

Bridgers and her all-white creative team may very well be unaware that the monster in their music video is, in fact, heavily symbolic of the extreme historical violence that surrounds the colonial and military relations between the U.S. and Japan.

The problematic Godzilla section of the “Kyoto” music video starts at around 1:41. Godzilla suddenly appears while Bridgers sings about her father sending her younger brother a late birthday greeting, which further reinforces the dissociative relationship between the lyrics sung and the images presented on screen.

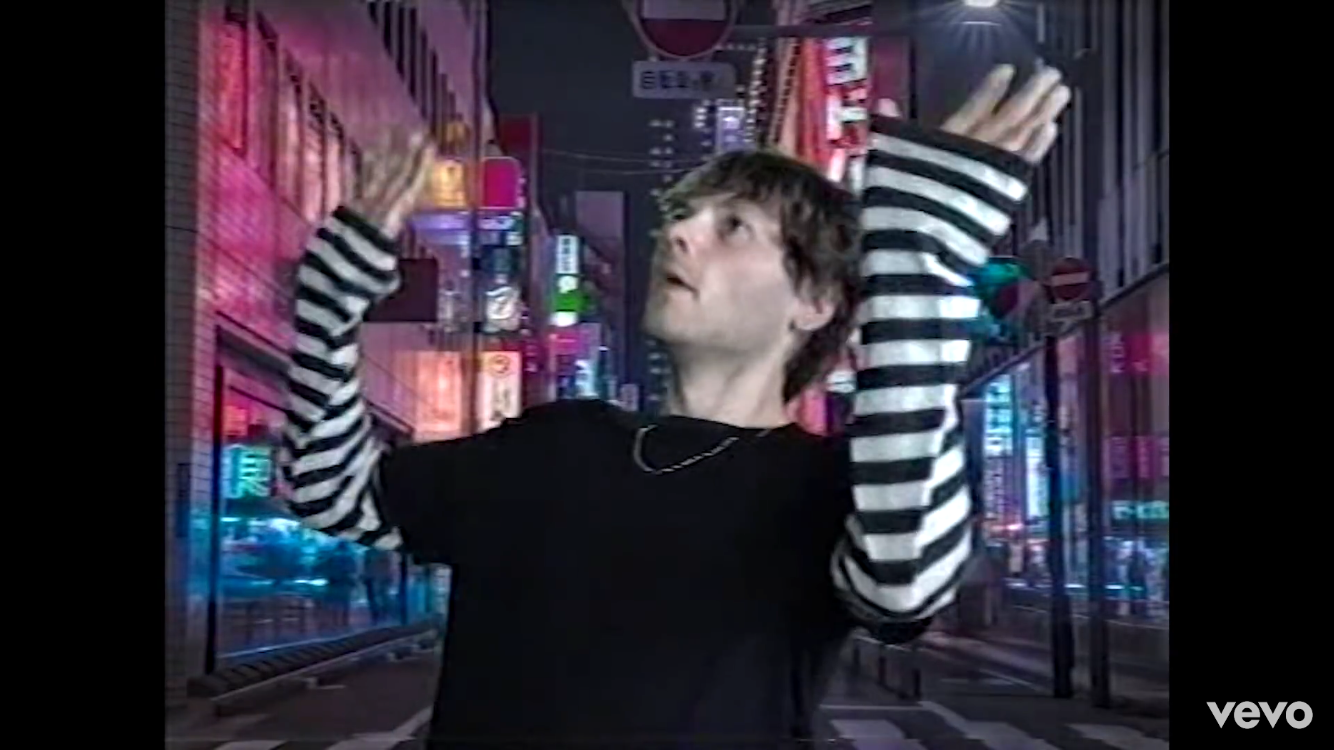

In this section of the music video, Bridgers and her white peers are positioned in front of a green screen backdrop of a Japanese neon cityscape. All four white people pretend to scream at the prospect of getting killed, eaten, and burnt alive while Godzilla attacks the pseudo-Japanese city.

While Bridgers is still singing about her father and brother, green screen images of fire start to appear, as well as images of a looming disembodied hand playing with a Godzilla toy. (While Bridgers sings the line, “Guess I lied” towards the very end of the music video, the same toy makes its final appearance at the foreground of a stock image of cherry blossoms).

Bridgers’s eyes suddenly turn red, and laser beams erupt from her eyeballs as she defeats a frightened-looking Godzilla. Then, the video cuts to an image of all four white people sticking their thumbs up in approval while situated against the same backdrop of a neon Japanese cityscape.

Here, Bridgers ignorantly presents herself as a white superhero who saves other white people from the terror of U.S. imperialism. As a monster whose origins stem from Japanese cinema, Godzilla has historically embodied the collective trauma that Japanese people have experienced due to U.S. military violence.

In an article about the symbolism of Godzilla, Sandy Schaefer writes, “A gigantic, prehistoric, dinosaur-like amphibious creature powered by nuclear radiation, Godzilla began as a metaphor warning against the dangers of nuclear proliferation in the wake of World War II and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Thus, the green screen images of fire in the “Kyoto” music video directly reference the violent flames that erupted from a series of powerful bombs detonated by the United States of America in Japan in 1945.

Perhaps without any sort of awareness of the implications of their creative decisions, the members of the all-white creative team behind the “Kyoto” music video were so ignorant as to place four white people at the center of the burning hellscape of a Japanese city being violently wrecked by the monster-embodiment of U.S. military bombs.

Might this particular section of the music video be a subconscious reference to Bridgers’s song “Savior Complex,” which appears on the same album? Will all four white people be swept away from pseudo-Japan by a “Chinese Satellite” in a sudden plot twist?

Is Bridgers herself aware of the violent and traumatic history that Godzilla represents, beyond the monster’s surface-level American existence as a mythical creature borne of the Japanese imagination?

With the same deceptive innocence and naivete of white children playing with plastic Godzilla toys, Bridgers and her all-white creative team reference the Japanese monster in the “Kyoto” music video as if the monster itself has absolutely nothing to do with the violent history of U.S. militarism in Japan.

By deliberately choosing to present herself as a white savior who triumphs against Godzilla, who in turn is the fantastical manifestation of extreme U.S. military violence against Asian people, one can’t help but wonder — who or what is Bridgers really saving, aside from the unfortunate mass appeal of white people singing about their personal problems in front of pseudo-Asian ornamental backdrops?

“Kyoto” as a Prime Example of White Ignorance and White Privilege

Surely, “Kyoto” has earned Bridgers a winning spot on the long and exhausting list of white artists who are obsessed with pseudo-Japan and aren’t afraid to show it.

Regardless of their individual levels of awareness surrounding the nature of their behavior and its subsequent impact on their surrounding social and cultural landscapes, white artists enact harm by utilizing marginalized cultures as mere content and backdrops for their creative work. When songs like “Kyoto” generate an abundance of wealth, public attention, and critical acclaim, this ultimately only benefits and privileges the white artists in question and their all-white creative teams.

In Bridgers’s case, the mass appeal of her song about her strained relationship with her father grossly overshadows the deliberate act of positioning herself as a skeleton-clad white woman in the foreground of a Japan that exists solely to serve her white imagination.

In “Kyoto,” Japan is no longer a real place. Rather, it is a mere fragment of Bridgers’s creative consciousness, swinging like a pendulum of images that white people have artfully manufactured for the global consumption of popular art and media.

If anything, the “Kyoto” song lyrics and music video have made it abundantly clear that Bridgers’s pseudo-Japan only exists to serve her career and to play an overwhelmingly minor role within the larger narrative of her song, which ultimately centers the white experience and renders it hyper-visible within the American (and therefore global) music industry.

- Paul Mescal, Phoebe Bridgers, and Phoebe Waller-Bridge Made a … ›

- Phoebe Bridgers Shares New Song, Details New Album – Popdust ›

- Phoebe Bridgers Became A Star In 2020 – Popdust ›

- Phoebe Bridgers and Maggie Rogers Cover the Goo Goo Dolls’ “Iris … ›

- 9 Up-And-Coming Folk Artists For Phoebe Bridgers Fans – Popdust ›