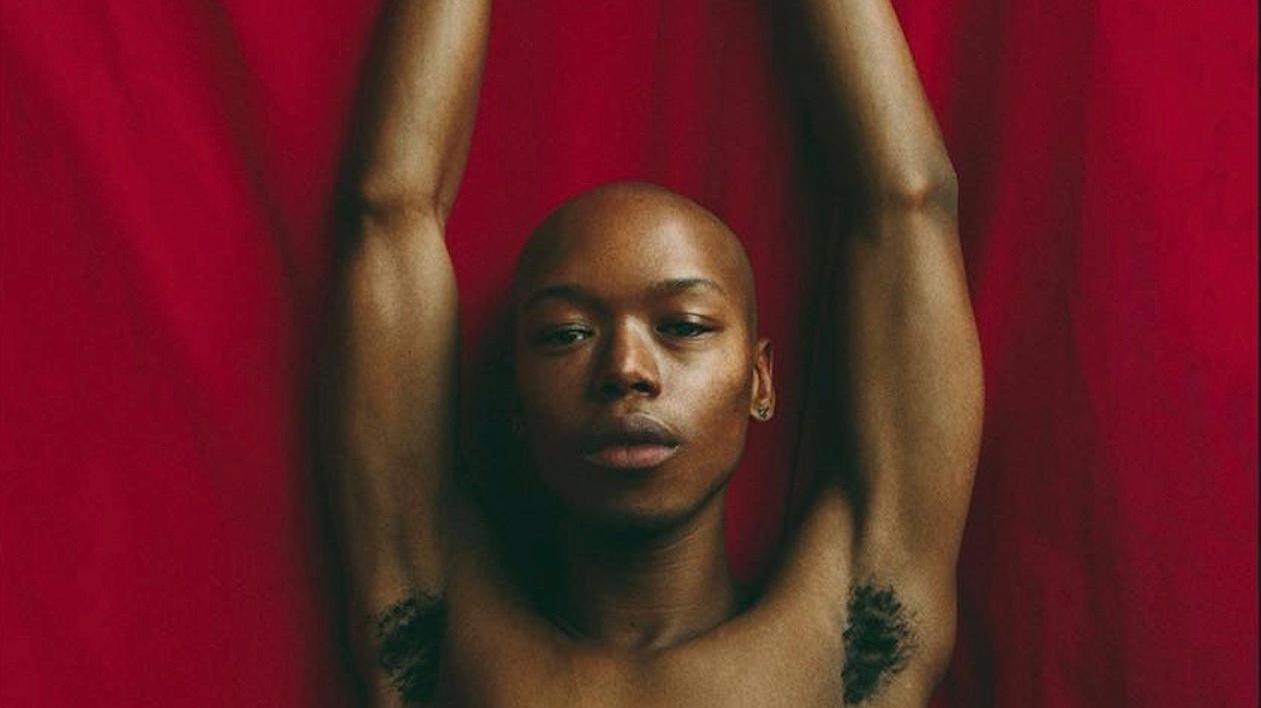

Nakhane

“Convenience and ease are your enemies, in my opinion. It’s not Instagram, it’s a work of art that’s gonna outlast your little life.”

Nakhane speaks with an easy poise, excitable with a dazzling energy. He’s been compared to queer luminaries like James Baldwin and David Bowie, and the comparison becomes clear when talking with him—the casual, almost-devilish way he articulates his brilliance.

Not to imply there’s any pretension or artifice to the South African artist or his work. In fact, his music cradles an unshaken honesty in the way he forces his past and his future into dramatic conversation. His latest single, “New Brighton,” a collaboration with English singer Anohni, unfolds in a characteristically dreamlike reverie: a warmly dancing drum anchors the track’s symphonic electronica wave, as Nakhane’s angelic voice soars above: “Never live in fear again / No, never again.” Nakane is as serious about his craft as he is loving, and the effect is nothing less than mesmerizing.

Popdust was able to speak to Nakhane before his June 29th performance in Sao Paolo’s Dogma Festival, in a conversation about his influences, his artistry, and (unexpectedly) the fashion sense of the Catholic Church. (“Look at the Pope! He looks great. All the colors? So camp! He’s basically in drag!”)

How long are you going to be in Brazil for?

Oh, God. So we arrived today, and then we play tomorrow, and then we leave the next day. So, about two and a half days?

God, so you’re going to be frazzled for a while.

Yeah, but I’m really used to it now. I think I know how to best take care of myself. Because I’m a singer, I know that I can’t go out and do things. I’m in the country by name only, by passport alone. [Laughs] My mind could be anywhere, my body’s here. I get to the country, I drink lots of water, I don’t drink alcohol, I try to eat as healthily as possible, I exercise, I play the show, and I get out.

Has the idea of taking care of yourself been something you’ve had to work on?

I suppose. You know, my first album was only released in South Africa. I didn’t understand how much of a toll not taking care of yourself would take on your body. Maybe not on your body, but on your voice. […] When I released my first album, everyone was talking about “the voice, the voice, the voice,” and then after we released You Will Not Die, everyone was talking about “the voice, the voice, the voice.” It’s really moving that people like my voice, but it also puts such a responsibility, such pressure, on me to take care of it. Because some people, at least this year or last year, are seeing me for the first time playing live. So they’ll come to a show, and maybe I’ve had a rough night, and [I’m] hoarse, not hitting notes, flat, sharp. And they’ll think the whole thing was made up, and that it was all the studio! We can’t have that.

So you have to take care of the equipment, basically.

Exactly. And I’m so jealous of my band and the crew. They can do things. They’re out now, gallivanting and sightseeing, having glasses of wine. If you drop a guitar, we can get you a new one, or if you fuck up your drums, we can get another set. If I fuck up my body, if I fuck up my voice, that’s it. You don’t get a second chance.

Your most recent single, “New Brighton,” was made with Anohni. What did Anohni bring to your vision for the song? And how do you think about collaboration in your own work?

This song took so long to get right. It was the first song I wrote for the album, [from] I think New Year’s Eve of 2013? And then we recorded You Will Not Die, and it was released everywhere except for the United States and some other countries, and [“New Brighton”] still wasn’t in that version. And then I performed it on some TV station in South Africa, and the label saw it, and they were like, “What song is this? This song is amazing!” And I said, “Well, it was part of the demos that you didn’t care for.”

So we re-recorded it, and re-recorded it, I think we recorded like three times. And still something wasn’t quite gelling. [And then] I had the idea of asking Anohni to sing on it. It was the perfect thing to get it right. […] She grounded it, you know? Even though her vocals are really massive. I wanted her to sound like an ancestor, to make me feel like I can take up space in the world. And she really brought the sense of urgency, but also comfort, love, validation, et cetera et cetera.

Nakhane

Nakhane

So, she helped put you in conversation with an ancestor over the course of the song?

Oh, my God, yeah. Completely. It’s almost like a call-and-response. She comes into the chorus, and we’re singing together, but she’s mixed higher. We tried different ways of mixing it, but our voices have similar timbres, so her vocals would just get lost. So I said to the engineer, “Fuck it, just blast her.” I used the example of the Iggy Pop and Cat Power song, “Nothin But Time,” where [Iggy] comes in and he just sounds like a Greek God.

And the fact that she understood that in your collaboration, and the song came out like that…

Well, she’s a genius. She’s one of the kindest musicians I’ve ever corresponded with in my life.

You’ve written a novel, you’re working on a second one, you’ve released a meticulous and cinematic album with You Will Not Die, and you’ve starred in a gorgeous and critically-acclaimed film (The Wound, 2017). What’s the significance, to you, of the variation of roles you take on as an artist?

Nothing’s different and everything’s different, right? What I like about being an actor is relinquishing control, and just being bossed around by a director. I like that it’s not about me. Nakhane doesn’t even exist, I’m not even Nakhane onscreen, I’m someone else. Whereas with my music, with my writing, with my literature, it’s so represented by my body, by my politics, by who I am, or I guess who people think I am. With acting, I get to put that away, and be of use to someone else’s ideas, to have no ego. I like that.

Music for me has always been there. It’s in my body. I was singing myself to sleep since I was four years old. I used to sing and walk to the bus station. I still do that, even though I live in London and people give me looks. [Laughs] And words gave me a sense of belonging, you know. I realized, “Oh, okay, I can read something, and it can make me feel something.” Written by somebody who’s next to me, like a love letter, or written by somebody who died 200 years ago, from a different country, generation, gender, sex, whatever. But somehow it travels through time and still touches you.

Would you say it’s about a degree of agency? Someone else’s work versus yours, in different artistic registers?

It is completely about agency, but it’s also about representation. Toni Morrison said if you have a story that hasn’t been told yet, you have the responsibility to write that story. With my novel, at least, what I was trying to make, I hadn’t seen, I hadn’t read. I could be wrong, because I haven’t read every book in the world, right? So there’s a little bit of an ego thing, like, “Oh, I’ve never seen this before. Let me write it, finally.” But I hadn’t seen the people that I was writing about in the way I wanted them to be. So I took it upon myself to do that.

Are there any contemporary artists, in South Africa or the world at large, that you feel are working in the same kind of space that you are, either in concept or in sound?

Oh, yeah, completely. I’m not in any way isolated, or special. There’s so many incredible musicians. There’s a performance duo called Faka from South Africa, they were performing in Sao Paolo as well yesterday, but I think they’ve left now. Two friends of mine, actually. They are incredible. They make me feel brave, you know? One of them, actually, I used to date, like ten years ago, and he taught me so much. To see them doing so well now in their work, it makes me feel…You know when you’re growing up and you’re twenty years old, and you all have these dreams, and then they do come true, but they come true for all of you? [Laughs] It’s really rare, but it’s really beautiful. And the work they’re doing is so different, that there’s no competition, that’s what I like about it. And yet driven by the same principles: freedom, visibility—but so completely different.

There’s another musician, called Thandiswa Mazwai. She’s a legend, she’s been around for a while, you know? But she shows you how incredible it can be for an artist to evolve through time, and still be relevant like 25 years later. And still be dangerous!

So that idea of evolution is important to you?

Yeah, what are you doing being stuck in—[Laughs] Okay, this might be a little bit problematic, but I’m going to say it anyway. When we were in Athens—there’s this idea when you go to European countries that have kept their things that they did in antiquity, because they destroyed other people’s stuff. They kept their shit, but destroyed everyone else’s, so it seems like they’re the only ones who are doing stuff. But I was in Athens, and a friend of mine—who is from Athens—said, “You don’t seem very impressed.” And I said, “I’m not. This was created 3,500 years ago. That’s great. Amazing. But I care about the now. What are you doing now, man?” And this friend had said, “Us Greeks, you know, [we] created culture 3,500 years ago.” And I said “Well, you mean like everyone else in the world?” What the fuck? This whole idea that certain civilizations were more elevated than others, which is complete bullshit. But in terms of evolution, and being interested in the now, that’s what I’m trying to be. I’m trying to live now. The past may help us in reminding us of what not to do, but it can also be dangerous in that we get stuck there.

I think one must always grow. I’m lucky…I’m 31 years old, and this stuff is only starting to happen for me now. For a long long time, in my twenties, I was really depressed. Like, “Oh my God! All my friends are getting married, and having babies, and their careers, buying houses. And I’m working in a bookstore.” Not that there’s anything wrong with a bookstore, but I have dreams, you know? Around 27, things started to really unify and collect. So, now, I’m a little bit older. I don’t need to party when I’m performing. After this, I’m gonna go home to England, I’m gonna be free for a week. I can party as much as I goddamn want to. [Laughs] But I have a project now, and so I have to be focused on that now. I take my work very seriously. I don’t take myself seriously, I think I’m an idiot, but I take the work very seriously. It’s a vocational thing.

There’s a sense of being called to it.

Completely. I really believe in that. I think it’s shamanistic.

Oh my God, oh my God. Chimimanda [Nqozi Adichie, author of We Should All Be Feminists] wrote about the danger of the single story, [and how] people who grew up in that world, or were cultured in that world, start to believe that’s the only story that they can tell, and that’s the only story that has value. And that the faces they see making those stories, or realizing those stories…[You believe] “I’m not worthy, I have no value.” People like me, queer people, queer stories, are not seen as having value. And that’s not true.

What I find so exciting about these times, right now, as ugly as they are—I mean, they’re also very beautiful. A series like Pose could not have existed in any other time but now! And it’s not just some kooky, weird avant-garde thing on the left you watch with your friends, it’s mass media. So yeah, there’s Trump, and yes, there’s Brexit. But there’s billions and billions of other people, and there’s billions and billions of other stories!

And there’s room being made for them.

Exactly.

Pose is so good, man.

I love it so much.

Your first album, Brave Confusion (2013) was much more folk-leaning in its sound, but since then you’ve transitioned into a more electronic, orchestral sound that showed up on You Will Not Die. What did you find in electronic music that you couldn’t find in other genres?

Well, it wasn’t necessarily much of a genre thing as much it was a tool thing. When I made Brave Confusion, all I could afford was my shitty acoustic guitar, and that’s all I wrote on. So when I recorded those songs, I was so naive that I thought that was the only way I could realize those songs. And it’s not that I dishonor those songs, because without those songs and without that album, I wouldn’t be where I am now. But cut to me recording You Will Not Die, and now I can imagine much more widely, and wildly. I can go, “Ooh, I want a sea of synthesizers.” And I can ask Ben Christophers [producer of You Will Not Die] to do that for me.

Whereas before I was a little bit more nervous to say that I didn’t like something, to command what I wanted in my work. And I really wanted to make a grand album, I wanted it to be operatic. Because I was writing about my childhood, my family….and I couldn’t write about my family in a timid way. The kind of music we were making was not timid, it was big and loud and over-the-top. It’s not about me saying “I want to sound like Brian Eno,” it’s more me going, “Oh, I can do whatever I want! We can get the synthesizers, we can manipulate the sound—we can live in a sound world now.”

You’re very open about walking away from Christianity, but it’s interesting to see how religious imagery and references to prayer crop up in your work. How does the faith you grew up in affect your storytelling, and why is its presence important to you?

I call Christianity my mother tongue, you know? Before you learn other languages, you speak the language your people speak in. And you can leave the country that you were born in, but the language will always be with you. I may live in England, but Christianity is still in me, I’ll never lose it ever. Whether I think it’s beautiful or not, it’ll always be there. Those were the first stories that I heard. They opened up my imagination. There’s some incredible storytelling in the Bible. So I use it now, instead of it using me. I have power over it, instead of it having power of me. That’s the difference. Because for so long, I was its tool. Or at least, people used it as a tool to manage me. To manage entire populations! What I’m interested in now is ,can you step away from it and still use this mother tongue, without it being so heavy and hateful and bitter?

The most interesting thing you do on You Will Not Die is how the lyricism about love and queerness—I mean, correct me if I’m misunderstanding, but it’s not really about juxtaposition with religious imagery, it’s like they’re inextricable.

Exactly. Exactly. I’m not interested in being clever about it. That’s nice, you can pat yourself on the back, but it doesn’t touch anybody, no one’s moved. If it doesn’t connect with me emotionally, because I make it, then it’s not gonna connect to anyone else. And since this is the language I’m using, then there’s no time for me to try and outdo it in this cleverness. You can’t outrun it…I’m interested in the romance between those languages, between life and the language of the Bible, and saying, “Okay, we’re divorcing, but I understand why you matter to so many people.” My mother is still a very conservative Christian, and I may not agree with her on certain things, but I understand why she’s still there. […] There’s always this idealized form of living, and then there’s the real one beneath it, which is what I’m interested in.

I really appreciate how You Will Not Die explores love, as something lacking, something sought, or something found, in yourself or in other people. What’s been the biggest part for you of bringing that sense of exploration to life?

That love is boundless, love is bigger than the constructs that we were born into, that we construct for ourselves. Since it came out in Europe in 2018, that’s been an exploration of mine—What is love to you? What can you do to make sure it’s something that you can pass on, with your work and in your life? It’s easy to sing about it and just live a different life, but I’d feel like a complete hypocrite. Lots of artists have been fine with that. Where they write the most beautiful, loving things and then they’re monsters in real life. So I’ve been trying not to do that.

Of course I fuck up, because I’m a human being. But again, the bigness of love, the malleability of it. It can withstand anything. And that can be really problematic, but it’s also really beautiful. This is so bad, and my poetry teachers would kill me, but it really is like water, in that it fits into any shape. Until it freezes over, and it’s done. But before that…before that, it’s life itself. How it allows itself to be used, but also how it uses you. How you may think it has no power over you, but it does. I’ve stopped trying to understand it.

At the end of the summer, you’re playing SummerStage in New York City. In your live performances, you have this really commanding stage presence, but you’re also creating this very safe environment, just in how you as a performer take up that space. What do you care most about communicating to a live audience?

That they feel like they can be the version of themselves that they want to be. I think Kim Gordon [of Sonic Youth] wrote an essay about how people go to a show so that they can believe in themselves, because they believe in that artist. So that safe space is really important to me, that a person can lose themselves, forget all their bullshit outside the door for that hour. Sometimes there’s such a distance between the audience and the performer. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in us feeding each other.