Miley Cyrus

By Kobby Dagan // Shutterstock

Imagine if, in the year of our Lord 2021, a white woman claimed to invent twerking.

She would be so swiftly canceled that there wouldn’t be a discussion. You’d log into twitter in an attempt to get in on the action and your timeline would be a mess of memes, carnage, and the occasional #woke thread straight out of Race Theory: 101.

In 2021, some people might defend whichever celebrity was trending in an #overparty hashtag, but the majority of the internet would guilt said white woman into making a teary apology on Instagram live.

However, this was not the case in 2013 when Miley Cyrus woke up and chose violence.

Gone was Hannah Montana. Gone were the long brunette locks of the Disney Channel Miley we knew and loved. In their place was a short haired blonde woman with grills, hoop earrings, and Jordan sneakers.

In an attempt to move away from her tween-star image, Miley chose the route of many former Disney Channel golden girls: embracing a completely new, emphatically wild image. For Miley, that image was a caricature of Blackness.

In the first single on her transitional album, Bangerz, “We Can’t Stop,” Cyrus brazenly talked about sex and drugs and alcohol, all to the refrain of, “We can’t stop / we won’t stop.”

It was bold. It was shocking. It was the song of the summer and, admittedly, a banger. Miley didn’t stop at provocative lyrics, however. As part of her new persona, everything had to change.

In the video, Miley’s face first appears in a grimace … as she slides gold grills onto her front teeth. Already, yikes, but it isn’t until the second verse that the song and the video take a turn for the worst.

Miley pulls a spoon out of a bowl of spaghetti-o’s to reveal letters that spell “TWERK.” As the audio sounds the lyrics, “My homegirls here with the big butts / shaking it like we at a strip club,” the video moves to show Miley in the center of the room, dressed in all white, surrounded by Black women as they all … twerk.

Miley Cyrus – We Can’t Stop (Official Video)youtu.be

This was the beginning of the end.

The twerking scene became the focus of the video. The dance was shiny and new to mainstream culture, and quickly Miley Cyrus became the face of it. While she never claimed to have created the dance move, she eagerly accepted her new reputation and basked in the press that cemented her new and wild, reckless persona.

Everyone was watching to see what she would do next.

With her next song, Miley ramped up her new image from grills and a Black backup dancers to a full rap song featuring Wiz Khalifa and produced by Mike WiLL Made-It.

The lyrics to “23 (J’s on my feet)” are seared into the deepest part of my brain, and I can’t think of them without hearing Cyrus’s squeaky lilting attempt to rap, or something approaching rapping, with the lyrics: “I’m in the club high on purp with some shades on / Tatted up, mini skirt with my J’s on.”

In this video, Miley is surrounded by a Black entourage, doing her best caricature of Black, hip-hop culture from her outfits to her mannerisms to those damn grills.

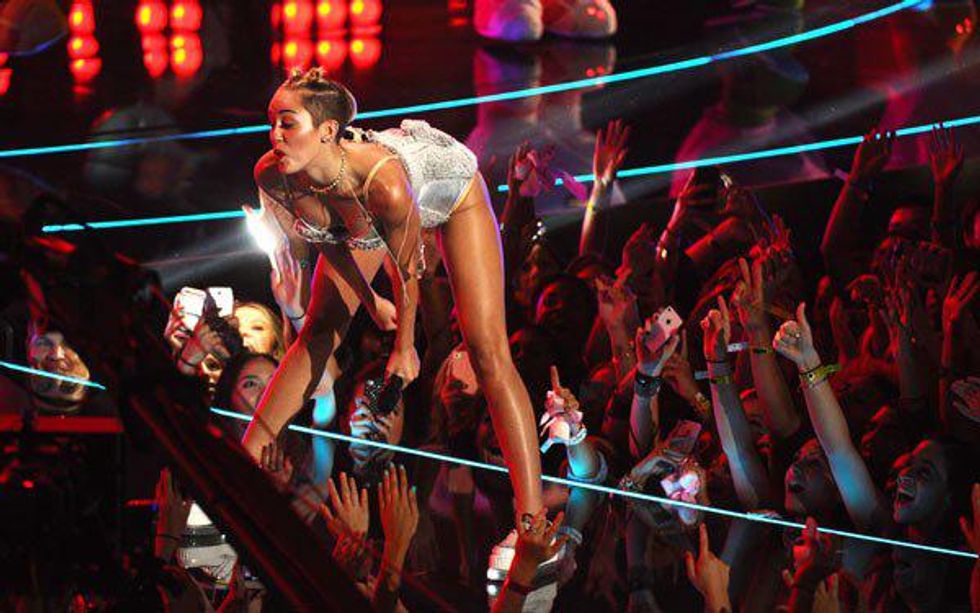

She followed all this up with a grand performance at the VMA awards, at which she wore “space buns,” a hairstyle appropriated from Black women’s natural protective style called bantu knots, and, once again, twerked surrounded by an entourage of Black women.

And while people were happy to gape and gasp at Miley’s transformation and audacity, Black women were pointing out the levels of cultural appropriation but were met with silence or even gaslighting.

In the mainstream, the conversation ended with personal responsibility — that Miley was just out of control and being wild and vulgar, traits that, to them, were only confirmed by her proximity to Black culture. Cultural appropriation was not in the common lexicon yet. But it was coming.

2013 was the midst of a renaissance in which Hip-Hop, rap, and, by proxy, Black culture were moving from the fringes to the mainstream, and so was Black activism.

That was Hip-Hop’s “golden year,” but it was also the year Macklemore was nominated for the Best Rap Album Grammy he later won over Kendrick Lamar’s masterpiece, good kid, m.A.A.d city. Yes, that was the year of Miley’s twerking, but the next year Beyonce would cleanse all our palettes by performing “Flawless” at the same award show with the word “feminist” behind her, which was still controversial at the time.

While there had always been mainstream, famous rappers and white fans of rap music, the tides were turning to usher in our current era, in which rap music and pop music played interchangeably on Top 40 radio, and Hip-Hop aesthetics were following suit.

The Guardian saw it for what it was, saying: “It became impossible, this year, to talk about popular culture without also talking about Hip-Hop: if Miley Cyrus’s twerking at the VMAs became one of the most discussed moments of the year, one of the reasons it did so was precisely because it was taking from hip-hop and stirring up a debate about cultural appropriation.”

While Miley insisted she was just having fun and being young, that recklessness was afforded to her by her whiteness. While she was all about throwing off her Disney image, her Disney image was the only reason anyone entertained her farce of an attempt at Hip-Hop.

I didn’t know whether to be relieved when, years later, Miley released the song and video, “Malibu,” which saw her washed up on a beach in a white dress, showing that she was back to her pop-country roots — no more of that rap stuff. Amidst this transformation, she swore off Hip-Hop, calling it “superficial and vulgar.”

While she also apologized for being “racially insensitive,” Cyrus had already accomplished what she had come to do without taking any responsibility.

She used the aesthetics of Hip-Hop culture to promote an image of herself that was proximal to the stereotype of a Black person — grills in, drinking “purp,” dancing “lewdly.” Once she was bored with those aesthetics and the judgment that came along with them, she abandoned them.

And her Black entourage? Nowhere to be found. After tokenizing and using Black women as props, Miley left that part of her career unscathed and pretty much forgotten by most of us.

Yet, it ushered in a new era. In 2014, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian would be on the cover of the September issue of Vogue — a moment I insist was the cultural reset. It was time for someone else to win the gold for cultural appropriation, and, with the help of Kanye and Kim’s status as a power fashion and Hip-Hop couple, cement the foothold Hip-Hop still has on popular culture today.

But before all that, there was Miley. Fastening her grills. Tying her space buns. Twerking in a desperate attempt to prove to us all that she was grown.