Music

Half In Love With Easeful Death – Marianne Faithful Dies At 78

…I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

– “Ode to a Nightingale,” John Keats

Marianne Faithfull – who died in her London home on January 30 at the age 78 – was deeply enamored of the Romantic poets, those mainstays of English Literature departments such as Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Blake. A bout with COVID in 2020 nearly killed her; lung problems stemming from the illness made singing impossible, and her last record (She Walks In Beauty, 2021) features recitations of some of those poets’ work set to various soundscapes.

Her health had long been problematic. COVID was added to a suicide attempt, drug addiction, breast cancer, a broken hip, Hepatitis C and emphysema. Given all that, the mere fact that she made it to 78 is remarkable. After all, Keats was dead at 25, Shelley at 29. Poets and popstars aren’t supposed to last long.

Faithfull’s story was always remarkable – as much for its transformations as its longevity and notoriety. 1964’s angelic blonde-haired soprano vanished from sight after an ill-starred romance with Mick Jagger and heroin, only to reemerge in 1979 as a ravaged, whiskey-voiced chanteuse on Broken English, a punk Lotte Lenya.

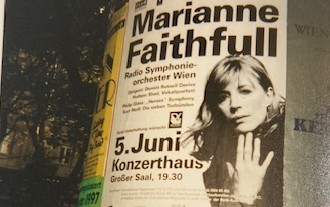

Comparisons with Lenya – arguably the definitive interpreter of the songs her husband Kurt Weill wrote with Bertolt Brecht in post-World War I Germany – are inevitable. Later in her career Faithfull recorded a number of Brecht/Weill tunes and appeared in The Three Penny Opera in Dublin’s Gate Theatre (1993) and The Seven Deadly Sins in Vienna (1997). Like Lenya, her sandpaper tones and powerful presence served the material well.

This Lenya-influenced version of Marianne morphed into her dowager years, a down-at-heels aristocrat of the rock world who made records with alt rockstars, Polly Jean Harvey and Damon Albarn.

On an extended stay in Alt Wien to work on a screenplay with writer/director Michael Hacker, I was in the Konzerthaus that evening in early June. I’d seen Marianne once before, at First Avenue in Minneapolis in April 1990. It was something to remember: a modestly-dressed, well-spoken Englishwoman, backed only by Barry Reynolds on guitar, transfixed a crowd of rowdy youngsters and had them hanging on every syllable.

Not long after that, I found myself working at Book Soup Bookstore in Los Angeles. Marianne came in several times during my stint there. One afternoon I was chatting with a colleague who ran the newsstand outside the store when Marianne wandered up to us. She needed a light for her cigarette. Could one of us oblige? I did, and the three of us chatted for a moment as traffic rolled up and down Sunset Boulevard. The bookshop was closing out the day shift, so my friend was handling fistfuls of cash in the register. One of us suggested, “We could take this money and head to Las Vegas.” Marianne beamed at us, blissfully contemplating the notion of robbery and flight, and then said: “Let’s.”

We didn’t run off with her. Sometimes I wish we had. She knew firsthand what Oscar Wilde meant when he wrote: “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.” She had a knack for turning bad behavior into something else. Many times she turned it into art.