Music

“Norman F**king Rockwell” Album Review: Lana Del Rey Is the Angelic Voice of the Apocalypse

31 Aug, 19

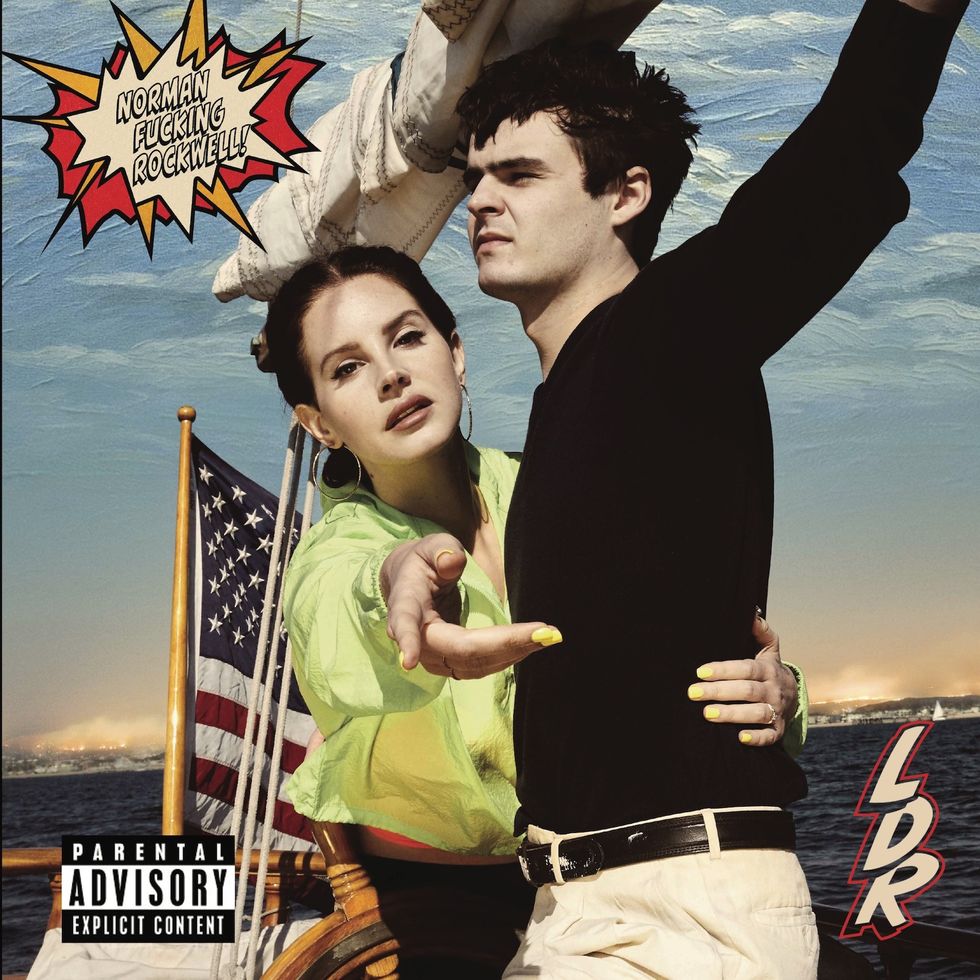

Press Photo

Lana Del Rey’s music is whatever you want it to be.

For some, it’s a collection of repetitive, glossy pop songs told from a subservient female perspective. For others, it’s gospel for the modern era, an encapsulation of all the dread and wonder that comes from living in a world on the brink of the apocalypse. For others, it’s transcendent and empowering, some of the best music of the modern era.

Lana Del Rey’s Norman F**king Rockwell is all of the above, depending on your state of mind. It’s both shallow and profound, high on delusions and yet piercingly self-aware. It is repetitive in parts, with some of the songs sounding rather similar, and it’s also clearly reminiscent of Del Rey’s previous works. The luxurious trip-hop beats and sharply whispered lyrics pull from Born to Die, with tracks like “Cinnamon Girl” (arguably one of the strongest on the album) recalling the chorus of “This Is What Makes Us Girls.” The man she’s singing about could be the same violet-pill-popping junkie who inspired Ultraviolence, though more likely it’s an amalgamation of her many different men, most of whom seem to be both self-absorbed and deeply depressed. There’s the stoned, beachy haze of Honeymoon and the political edge of Lust For Life.

Like all of Del Rey’s music (and also like ogres), Norman F**king Rockwell has innumerable layers. Each song could be about a romantic lover, sure. But behind all the brokenhearted melancholia there’s a clear sense of independence and power. This is on full display in “The Best American Record,” which finds Del Rey recalling her early ambitions, and in “Love song,” where she sings, “In your car / I’m a star / and I’m burning through you.” And of course, “Mariners Apartment Complex” (one of the album’s strongest) directly addresses criticism, ending with Del Rey repeating, “I’m your man” as synthesizers smolder.

Overall, this may be Del Rey’s most mature and opulent album yet. Some of these songs possess the expansive ambition and theatricality of Fleetwood Mac and David Bowie and the trippy grain of Jefferson Airplane, but they also defy direct comparisons to any body of work but her own. Her voice sounds stronger than ever, soaring effortlessly above producer Jack Antonoff’s excellent production.

Antonoff’s work is also a standout in itself; he layers dozens of sounds and perfectly mixes them so that each bell, violin, horn, and guitar peal shines through in their own way, resisting even a hint of muddiness. Each track feels fully developed, meticulously orchestrated, and high-drama. Slipping into them can feel like stepping into a hot tub or, maybe more accurately, feeling the edible kick in as you fall into a hot spring on the edge of a cliff in Big Sur. To fully appreciate Del Rey’s music, you have to surrender to it, let it take hold like a drug.

This is partly why Del Rey has such a devoted legion of fans who cling to her every move, tracing her influences and visuals with the reverence of disciples or cult members. If you let yourself fall into the Lana Del Rey universe, there are endless labyrinths to be followed—her innumerable artistic influences range from esoteric scientists and religious thinkers to, on this album, the Beach Boys and Bon Iver. There are also her countless unreleased tracks, most of which can be found on YouTube, which reveal the artist’s obsessive devotion to her craft. In some ways, Norman F**king Rockwell feels like the culmination of this long, tumultuous career.

Del Rey and Antonoff have mixed almost all of Del Rey’s older work together to create a psychedelic dreamworld built on pop chords, flickering echoes, and radiant strings that come together to take the desperation that has always characterized Del Rey’s music to new heights. This is noticeable on “California,” where Del Rey begs a struggling lover or friend to come back to America. “I’ll throw a party,” she says. “We’ll dance till dawn.” These lyrics are sung out with overwhelming angst, over a cluster of grinding synthesizers, giving sonic life to the complex feeling of wanting nothing more than to save someone you love, while knowing that you can’t do much other than distract them and love them to the best of your flawed abilities.

The same idea could be applied to the way that Del Rey talks about her own emotional state. Her music has always painted sadness in a seductive light to some extent, which may not always be the best blueprint to follow—and yet on this album, even more than ever, Del Rey practices a kind of radical acceptance of her own emotions and desires. All feelings, kinks, and mistakes have always been safe in her universe, and nothing goes too far. “You don’t have to be cooler than you really are,” she whispers.

Lana Del Rey’s music has always felt like a release. Her world is one where sadness can coexist with love and pride, where hope can coexist with resignation. There’s an emptiness at its core, but she surrounds it with so much theatricality and mythology, with images of neon lights and beaches, endless parties and passionate fantasies, that the sadness edges on euphoria at times. That’s partly why Del Rey’s fans love and relate to her so much, and why she’s poised to become the definitive scorer of the apocalypse. This is the perfect music to listen to as you lament your latest heartbreak or scroll through meaningless Instagram feeds for hours, or watch a hurricane speed toward Florida in real-time.

As with everything that Del Rey has created, despair never sounded more beautiful. Here, it sometimes even sounds like freedom.

Norman F*cking Rockwell!

- Norman Fucking Rockwell! (album) | Lana Del Rey Wiki | FANDOM … ›

- Lana Del Rey – Norman Fucking Rockwell! Lyrics and Tracklist … ›

- Lana Del Rey Says ‘Norman F*cking Rockwell’ Will Be Out Next Month ›

- Lana Del Rey on Trump, Kanye and the Right Time for a Protest Song ›

- Lana Del Rey: Norman Fucking Rockwell! review – an artist you can … ›

- Lana Del Rey Details New Album Norman Fucking Rockwell … ›

- Lana Del Rey’s new album ‘Norman Fucking Rockwell!’ – everything … ›

- Lana Del Rey’s “Norman F— Rockwell” dazzles: review – Los … ›

- Norman Fucking Rockwell’ Review: Lana Del Rey’s Best Album | Time ›