CULTURE

The Strange Intersections of K-Pop, Korean Culture, and American Fascism

27 Jun, 20

American Fascist

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra (Unsplash)

In 2016, young and extremely online white men began simping hard for Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy on sites like 4chan, Reddit, and (for the particularly hateful/socially maladjusted) 8chan.

Calling themselves “centipedes” because of their and their hero’s supposed ability to navigate through the worlds of politics and Internet culture (while grossing everyone out), these young men were among Donald Trump’s most vocal supporters. Encouraged by the anonymity and one-upmanship of their online forums, they were also among the most overtly xenophobic.

Along with cartoon memes featuring heavily-muscled versions of Donald Trump promoting police brutality and Pepe the Frog as a Nazi, they shared their opinions on gender roles, racial differences, and the descent of liberal manhood into “cuckdom”—as evidenced by the fact that they tended to be less hateful and racist than Alt-Righters (“cuck” being a reference to the “cuckold” genre of adult videos which often feature white men watching and being sexually humiliated while their spouses engage in sexual acts with Black men).

A hallmark of the movement was its ability to appropriate innocuous artifacts of Internet culture and turn them into symbols of hate. Pepe the Frog, for instance, was a beloved Internet icon for years before anyone pretended to like Donald Trump. His emotive cartoon face was used to express sadness and sardonic wit and recontextualized into a wide variety of “rare pepes.”

Cribbed from the work of comic artist Matt Furie, Pepe was never a symbol of hate until these communities of “pedes” started putting him in Klan robes and SS uniforms. But once that happened, it was too late. In 2017, Furie killed off his beloved character in an effort to disown what he had become.

A similar, but more complex trajectory has taken place with some of the other culture that “centipedes” appropriated for the movement. Closely aligned with self-proclaimed “hardcore” gamers—many of whom found their way into far-right politics through the anti-feminist “gamergate” movement—Trump’s young fans adopted some of the slang of the online gaming world.

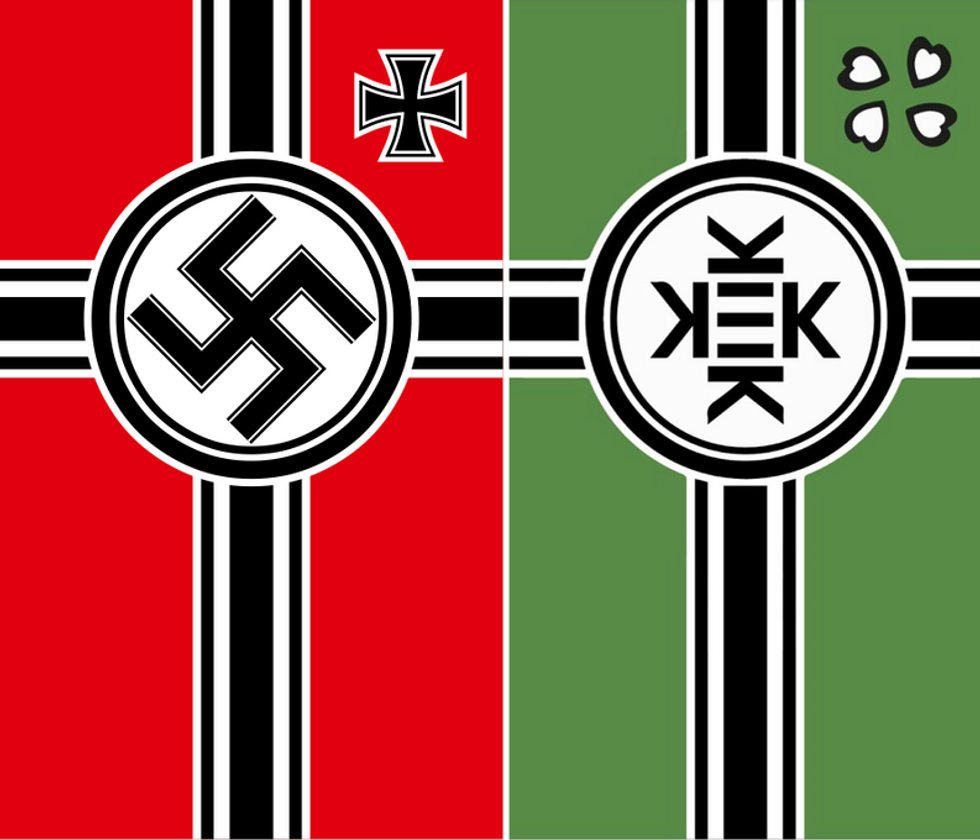

Specifically, they stole the way Korean gamers expressed laughter in text—”kekeke”—and started referring to pro-Trump memes they enjoyed as “topkek.” They even started referring to themselves and Pepe the Frog as residents of “Kekistan,” an imaginary country represented by a flag based closely on the Nazi Wehrmacht flag… All for the lulz.

White men of this ilk—even the openly white supremacist and white nationalist among them—often have soft spots for Asian culture, but they tend to have deeply confused ideas about what those cultures are. They tend to view Asian people as “model minorities,” frequently fetishize Asian women as submissive and quiet, and generally believe Asian societies to be closer to their ideal version of America: homogeneous and traditional with clearly enforced hierarchies.

To the extent that these people cared whose culture they were using in christening their homeland “Kekistan,” they might have expected Koreans to be on their side. As much as they were annoyed at Korean director Bong Joon-Ho’s brilliant anti-capitalist parable Parasite sweeping their formerly oh-so-white Oscars in February, they could hardly have guessed how big a role Korean culture would end up playing in pushing back against their fascist, pro-police, anti-Black, all-lives-matter nonsense.

But reality is far more complex than they tend to think, and it has been thrilling—though not necessarily surprising—to see Koreans and K-pop fans from around the world join the Black Lives Matter movement and systematically drown out fascist voices online by appropriating their anti-BLM hashtags on Twitter.

In Seoul, demonstrators marched in solidarity with the American Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Floyd’s horrific killing, and on Twitter K-pop superstars BTS released an official statement of support.

Since then their fans (the so-called “BTS ARMY”) and much of K-pop Twitter have made it their mission to disrupt hashtags like #WhiteLivesMatter, #WhiteOutWednesday, and #QAnon—referring to the bizarre pro-Trump conspiracy theory. They even registered by the thousands for Trump’s Tulsa Rally on the 20th, setting up the laughably disappointing turnout.

K-pop fans are making it impossible for racist messages to flourish effectively on the platform, flooding each new trend with unrelated K-pop videos and images that bury the hate.

And as new as this trend is, none of it is really that surprising. The roots of K-pop are in young people rejecting traditional music and style and making something new—heavily influenced by Black American culture and often with political messages critical of government power. And recent Korean history has been defined by mass protest movements in the face of brutal governmental efforts to suppress them—including student protests in the 80s that toppled a US-backed military dictatorship.

While many Americans are still in denial about how real the problems in our current system are, the rest of the world sees, and supports the protestors standing up for what’s right.

So now, three years after the Alt-Right took their “Kekistan” flags and Pepe signs to march in Charlottesville in favor of more oppression and more brutality, K-pop fans are appropriating their language online to drown out hate and fight for liberation and justice. Kekeke.