CULTURE

White Supremacy and Erasing American History: John Wayne’s Son Pushes Back Against Airport Name Change

30 Jun, 20

John Wayne Airport

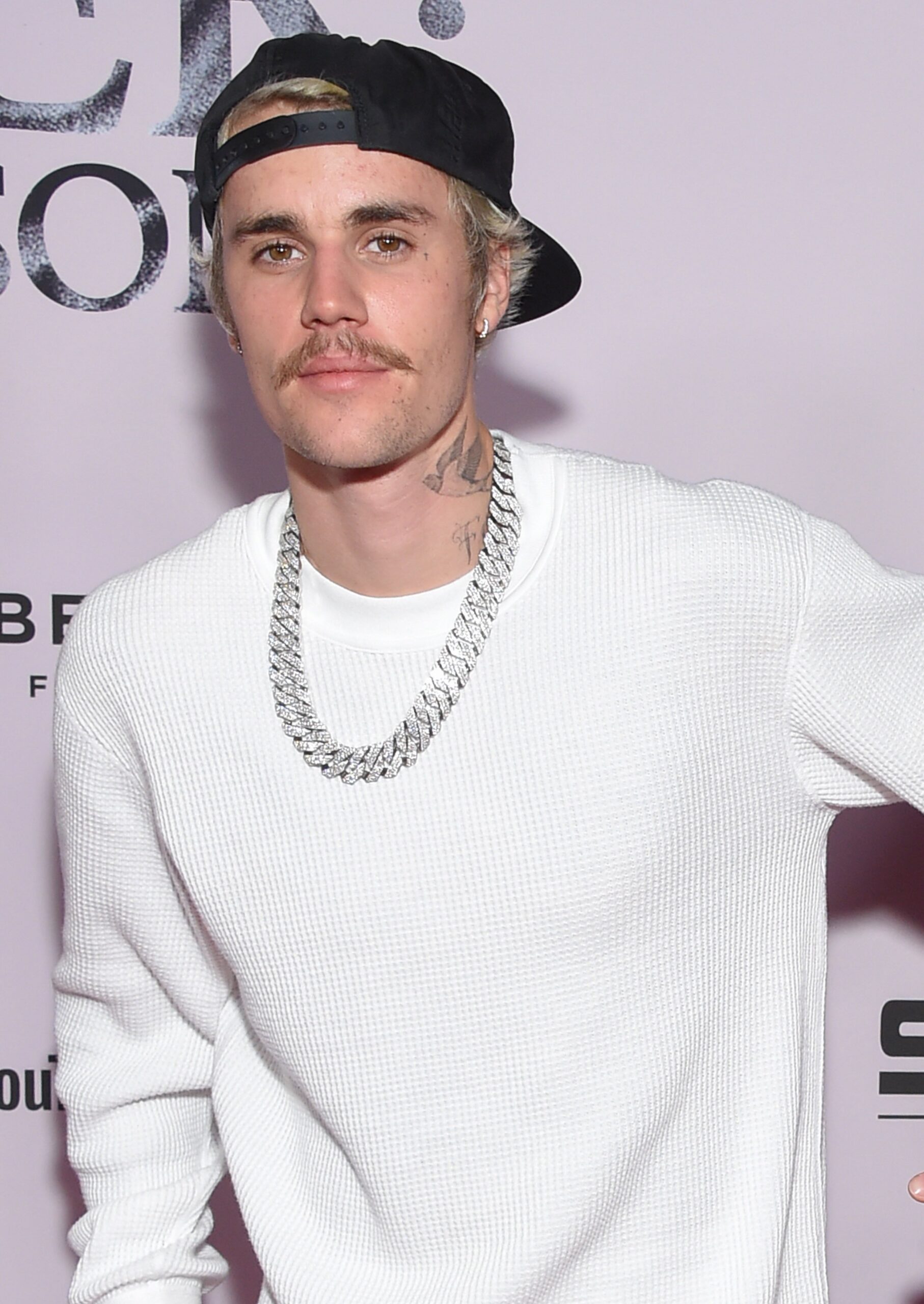

Photo by Carter Saunders (Unsplash)

In Orange County this week, a group of Democratic politicians has been pushing to remove John Wayne’s name as well as a 9-foot statue of the actor from John Wayne Airport, but John Wayne’s son is pushing back.

America has always struggled to reckon with the crimes of its past. While Germany has made a national project out of remembering the evils of the Nazi regime, America prefers to either deny that our nation’s crimes were as bad as they sound or to shrug them off as too long ago to be worthy of attention.

Yet somehow, in that hazy distant past, beyond the realm of clear facts or moral concern, we manage to idolize and identify with a few sainted figures—like the slave-owning founders who enshrined the national values of liberty and justice for all (as long as you have some very strange definitions of the words “liberty,” “justice,” and “all”).

We don’t consider them to be people—just as self-serving and broadly ignorant as people tend to be—rather, they are embodiments of noble concepts. They form a pantheon of American ideals, and every once in a while we add a new member to the lineup. And when people question the pantheon, Americans get a bit defensive…

One of the more recent entrants to the class of American godhood is the man who spent decades embodying the ideal of rugged individualism as a hero of wars and the west on the silver screen.

John Wayne: a figure so iconic that, after his death in 1979, a major airport was almost immediately renamed in his honor. But now protests against police brutality and the horrific killing of George Floyd have revived the push to remove memorials to Confederate generals and other figures of past sins from our cities.

And in this climate, it’s hardly surprising that people are looking back at John Wayne’s old interviews and questioning the choice to name an airport after a man who openly expressed such awful opinions. What is slightly surprising is the way his son, Ethan Wayne, decided to defend his father in an official statement on Monday.

Referring to a recently resurfaced 1971 interview with Playboy that has become central to the controversy, Ethan Wayne—who also happens to be the president of John Wayne Enterprises (profiting off his father’s favorable image with branded face masks and shot glasses)—said of his father that it would be “an injustice to judge him based on a single interview, as opposed to the full picture of who he was.”

No doubt the same could be said of any person—one conversation cannot possibly contain the complexity of an individual, and it’s no doubt true that “The Duke” had many good qualities, and he was probably a great father for Ethan. But on his specific claim that his father “was not a racist,” that single interview offers quite a bit of relevant insight

The John Wayne Playboy Interview

For a start, there’s the excerpt that has received particular attention, wherein John Wayne says pretty much the opposite of “I’m not racist”:

“I believe in white supremacy until the Blacks are educated to a point of responsibility. I don’t believe in giving authority and positions of leadership and judgment to irresponsible people.”

In response to the outcry over this comment, Ethan Wayne said of his father, “The truth is, as we have seen in papers from his archives, he did not support ‘white supremacy’ in any way and believed that responsible people should gain power without the use of violence.” But this is nonsense.

Leaving aside the arguments of people like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. that violence is often a necessary tool against oppression, John Wayne clearly excluded “the Blacks” as a monolith from the category of responsible people in his statement. He also spoke in the same interview of his openness to the idea of “all-out war” in Vietnam. How does that square with the idea of “gaining power without the use of violence?”

When asked about the added barriers for Black Americans to obtain the education “to a point of responsibility” that he seems certain they lack, John Wayne goes on to say, “I don’t know why people insist that Blacks have been forbidden their right to go to school. They were allowed in public schools wherever I’ve been.”

Perhaps he missed the part where, for nearly a hundred years after the abolition of slavery, legal segregation was maintained in most of the US, relegating Black Americans to underfunded and understaffed schools that were not officially recognized as grossly unequal and illegal until the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education (only 17 years before the interview)—an injustice that remained unresolved in many cases until well into the 70s.

Wayne must have missed the story of Medgar Evers suing to force Jackson Mississippi to integrate its schools in 1963 (eight years before the interview)—only to be murdered by a white member of the city council. Though, in fairness, John Wayne would be long dead before Medgar Evers’ killer was finally convicted.

Wayne must have missed the way that Black Americans remained stuck in neighborhoods that were relics of white flight and racist redlining practices. Or else he didn’t notice how that kept home prices low, preventing Black families from accumulating wealth and resulting in inner-city school systems (funded largely by property taxes) being as underfunded and segregated as ever.

Throughout the Playboy interview, Wayne is dismissive of each possible grievance of Black people, Native Americans, and anti-war protesters. He insists that everything was too long ago to matter or was never really that bad anyway.

John Wayne on Native Americans “Selfishly” Defending Their Homes

In response to Native American activists occupying the island of Alcatraz and seeking reparations from the US government, he says, “They should pay as much for Alcatraz as we paid them for Manhattan. I hope they haven’t been careless with their wampum,” and, “What happened between their forefathers and our forefathers is so far back—right, wrong or indifferent—that … I don’t know why the government should give them something that it wouldn’t give me.”

To clarify his comments, wampum was a form of shell-based currency used specifically by Eastern Woodland Tribes before European settlers overproduced it to the point of hyperinflation and obsolescence. And as for the claim that it was “so far back,” the American government continued pushing Native American Tribes into smaller, less desirable territory well into the 1890s (arguably long after), meaning there was no doubt still Native Americans alive in 1971 who had memories of being resettled.

Wayne also said that he felt no guilt about how Native Americans were treated because “our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

Which is such a disgusting fantasy—if anything it was about gold and other resources, not survival—that it kind of explains why he constantly walked like he’d just pulled his head out of his ass.

John Wayne on Slavery

Wayne is even worse about burying the issue of slavery in the distant past, saying, “I don’t feel guilty about the fact that five or 10 generations ago these people were slaves.” A generation is generally considered to be between 20 and 30 years, so if we’re being generous we could say that, at most, five generations had passed since the abolition of slavery in the United States.

But Wayne was born just 42 years after the end of the Civil War. If he’d cared, he had plenty of opportunity to interact with people who lived through the horrors of chattel slavery. Even at the time of that interview, there was at least one formerly enslaved man still alive. If he had cared to know them, John Wayne may have realized that many of his contemporaries were the children of formerly enslaved mothers and fathers.

It’s not an issue buried in the distant past unless we imagine that trauma was erased as soon as enslavement was replaced by share-cropping—and that their children didn’t take on any of the burden of that overwhelming tragedy in a society that continues to dehumanize them.

But for John Wayne it wasn’t enough that there were systemic and generational struggles. From his view, activists had no right to criticize society if they couldn’t tell him “where in the world they have it better than right here in America.” It’s certainly true that racism is a global institution, but that’s hardly a reason not to fight it at home.

In another deeply offensive interview a few years later (despite Ethan’s claims that his father was later “pained” by the Playboy interview because “he realized his true feelings were wrongly conveyed”), Wayne extended that idea to an absurd degree, saying, “They live as well here as they do in any other country over [the last] 199 years” (which is another blatant fabrication he must have found while rooting around in his Duke).

John Wayne’s Ordinary Racism

This is undeniably what racism looks like—or what it looked like in “polite” America in 1971. What may have Ethan Wayne confused is that his father never seemed to him or most of the people around them like a hateful or bigoted person. Why would he? At the time, this flavor of racism was perfectly ordinary.

Three years earlier, the assassination of Martin Luther King (which may or may not have been planned by the FBI) had been met with mixed reactions from white America. A shocking number of people felt that he had brought it on himself.

In that context, John Wayne’s beliefs that Black Americans just needed to educate themselves into equality and that “any Black who can compete with a white today can get a better break than a white man” seem almost tame—as absurd as they are.

But that isn’t enough to earn him a pass, because John Wayne wasn’t just an actor with some ordinary bigotry—not just a product of his time. He was a man with a huge cultural influence. One of a handful of people shaping that era of American society and the decades since. As an actor, a director, and a producer, he was massively popular, and his views came through not just in interviews but in the stories he chose to tell.

John Wayne had a tremendous power over culture, and as such he had a duty to educate himself “to a point of responsibility.” If he had listened to leftist Hollywood figures espousing egalitarian and democratic values—rather than playing a central role in Red Scare witch hunts to force them out of show business—he could have avoided expressing such awful ideas.

American Propaganda and the Baby Boomer’s Love for John Wayne

Instead, he took the common idea of American hyper-individualism, amplified it, and blasted it through war movies and westerns into the brains of generations of Americans. Even in that 1971 interview—when he was already in his 60s, they talk about how popular he remained with young people and acknowledged that his movies amounted to American propaganda.

Those young people he was propagandizing were raised on John Wayne as the image of the ideal American man. As Ethan Wayne puts it, his father “stood for the very best for all of us—a society that doesn’t discriminate against anyone seeking the American dream.”

A rugged loner favoring personal responsibility, espousing the meritocracy. From this perspective, any individual’s suffering is their own fault. And if a massive group of Americans is suffering…then there must simply be something wrong with that group.

The Green Berets (1968) Official Trailer # 1 – John Wayne HDwww.youtube.com

That seed was planted, and it grew as those children became a generation of adults with no faith in government and no belief in the social contract. A generation that went on to fall in love with retired actor Ronald Reagan—another star of war movies who managed to avoid actual combat (and now has an airport named after him). A year after John Wayne’s death, that generation of John Wayne fans elected Ronald Reagan to the presidency.

Ronald “small government, evil empire, welfare queens, trickle-down economics, disproportionate sentences for crack cocaine” Reagan. Another rugged anti-communist individualist. John Wayne by another name. So-called personal responsibility at the expense of people who are already disadvantaged.

Nearly four decades later, at a John Wayne-themed campaign rally for Donald Trump, John Wayne’s daughter Aissa Wayne said, “We need someone like Mr. Trump with leadership qualities, somebody with courage, someone that’s strong like John Wayne,” adding that “if [he] were around, he’d be standing right here instead of me.”

Erasing the Past

Ethan Wayne rejected the idea that his father would have supported Trump’s candidacy, because Ethan Wayne is in denial about who his father was. His statement went on to say, “My father believed that we can learn from yesterday, but not by erasing the past.”

But erasing the past is exactly what Ethan is doing now, and it’s what his father loved to do when it came to the oppression of minority groups in America—as when he made a movie about the Battle of the Alamo without acknowledging that the Americans defending the Alamo were fighting in part for the right to own enslaved Black men and women.

There is no point in commemorating the past or our important figures if we forget who they really were. Fortunately, at the end of his Playboy interview, John Wayne states exactly how he’d like to be remembered. He doesn’t mention airports being named after him, or his children selling John Wayne-brand whiskey and work gloves to live comfortably off his rugged image. He says, “I hope my family and my friends will be able to say that I was an honest, kind and fairly decent man.”

His children may still recall him as personally kind and decent, but if they want to claim that he did not believe in white supremacy, they are taking his honesty away from him.

And if we can all be a little more honest about who he was and the kind of influence he had on our culture, then we should all be fine with taking his name off that airport.