NPR

The ’90s were a confusing time for children.

We had toys that chewed off fingers, the worst Happy Meal prizes of all time, and presidents who acted hip by playing saxophone on TV. And when we wanted to escape all that, we had not-quite-right cartoons, from blatant racial stereotypes to animated bloodletting. But how “problematic” were our favorite cartoons? As much as we talk about call-out culture and use “social justice warrior” as a swift Twitter insult, what’s changed our perception of media since the ’90s? And what about media has changed?

As the elders of the Millennial generation, ’90s kids were raised on the sexualized illustrations and political incorrectness of our most beloved cartoons. John Kricfalusi, creator of the wonderfully crude classic Ren & Stimpy, did it on purpose. He described his renegade approach to cartoons: “I’m on the kids’ side…you have to go to church on Sunday, you have to listen to your parents give you rules after school, you have to do your homework…You don’t want to get morals in your television shows, movies, and cartoons.” True to form, Ren & Stimpy featured plenty of disturbing plots and discomforting images. In one episode, Ren experienced the real-life nightmare of all his teeth falling out and exposed his rotting gums to the nation’s children. The show frequently relied on graphic body horror for ghoulish humor about how gruesome and disgusting the world is, from self-mutilation to showing realistic humans’ wrinkled and hairy butts while they had a “family bath.“

But why does it matter what we watched as kids? After all, climate change will endanger half the human race by 2050. The Mueller Report has proven that adults never do their homework. Soon, Game of Thrones will end forever—adults have real problems! To put the ’90s’ freaky cartoons into context, bored social scientists have calculated that the average child with access to a TV watches about 18,000 hours of programming from kindergarten to high school graduation—which frankly sounds like a ton of fun and isn’t alarming whatsoever. The same scientists decided to look at how if at all, cartoons shape a child’s mind. They concluded that cartoons improve a child’s spoken language but can also enhance aggressive behavior. So we really should use our words in a fight, because apparently, cartoons made us good at it. But New York-based psychotherapist Dr. Laurel Steinberg also told Vice that “cartoons model higher frustration tolerance and activate a person’s problem-solving abilities.”

So, if watching cartoons helped us learn how to solve problems, what should we do about problematic cartoons? What is there to learn from them, and how do we address the problems they present, from gory violence to racism and sexism?

Case Study #1: Apu Nahasapeemapetilon and Why Context Matters

Giphy

Giphy

In addition to making TV history with its refusal to die, The Simpsons has an unabashed legacy of using racial stereotypes as the foundation for jokes. In particular, the show’s been plagued by controversy surrounding the South Indian character, Apu Nahasapeemapetilon. Apu owns Springfield’s Kwik-E-Mart, has a colorful backstory about earning a Ph.D. in Computer Science before emigrating to the U.S. (one joke is that he graduated first in his class of 7,000,000 students), and he has a very thick accent, voiced by the white comedian Hank Azaria.

In 2017, comedian Hari Kondabolu released his documentary The Problem with Apu. The second-generation American describes Apu as “one man who haunts me,” citing the larger implications of The Simpson’s treatment of race and America’s general lack of representation of many marginalized identities. He interviews other South Asian comedians and actors like Aziz Ansari and Kal Penn, as well as Whoopi Goldberg, to whom he asks, “Is Apu a minstrel?” referring to the racist propaganda that encouraged Black stereotypes in the early 20th century.

The Problem With Apu – Official Trailer | truTVyoutu.be

But The Simpsons’ brand of satire seems to justify a degree of mockery. So the central question is: Is the character of Apu racist or is it making fun of racist stereotypes?

According to Kondabolu, it all depends on the character’s context. His criticism of Apu isn’t solely grounded in the fact that The Simpsons panders to Indian stereotypes. The problem, the comedian argues, is the character’s significance in the context of American media. Actor Utkarsh Ambudkar (The Mindy Project) agrees: “The Simpsons stereotypes all races. The problem is we didn’t have any other representation.” In short, when a mocked stereotype is the sole representation of that identity on mainstream TV, “it’s funny because it’s racist,” Kondabolu argues.

The Simpsons creator Matt Groening dismissed the entire controversy, tellingUSA Today, “I think it’s a time in our culture where people love to pretend they’re offended.” The Simpsons even dedicated an episode to responding to the Apu controversy. In season 29 (seriously, when will this show end?), the episode “No Good Read Goes Unpunished” features Marge Simpson grappling with her favorite childhood book having racist stereotypes in it. At one point, her daughter Lisa says, “Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?” The shot quickly changes to a photo of Apu, who hadn’t had a line in three years due to the writers’ and producers’ own concerns that the cartoon was inappropriate. Additionally, Azaria decided to stop voicing Apu because he felt “it was the right thing to do.”

So, did censoring the character solve the problem?

Of course not. TV producer Adi Shankar criticized the decision, saying, “It’s not a step forward, or step backwards, it’s just a massive step sideways. After having read all these wonderful scripts, I feel like sidestepping this issue doesn’t solve it when the whole purpose of art, I would argue, is to bring us together.” Hank Azaria himself has said that the character he’d voiced for over a decade shouldn’t be continued if it does more harm than good by mocking real people’s experiences rather than representing them.

Actually, Azaria’s responses are the perfect guidewire to trace our modern sentiments on what constitutes offensive art, especially when it’s satire. In 2018, he told Stephen Colbert that he wants more inclusion of all voices, including South Indian, in both the writers’ room and as voice actors, and so he would be happy to “step aside” in order to let that happen. In a 2007 interview, however, he was more frank about the producers of The Simpsons approaching him about the role and asking him, basically, “Can you do an Indian accent and how offensive can you make it?”

2018:

Hank Azaria: ‘The Right Thing To Do’ With Apuwww.youtube.com

2007:

Apu from the Simpsons on Paltalk and DailyComedyyoutu.be

Apu debuted in 1990, and, according to the writers, he was funny for over a decade before they started to wonder if he was too problematic for TV.

Case Study #2: Johnny Bravo and Why Intention Doesn’t Matter

Giphy

Giphy

In its inception, the appeal of Johnny Bravo was to watch “the misadventures of a dumb blond egomaniac who is deluded about his own manliness.” From 1997 to 2004, the cartoon mocked the titular character’s narcissism, abrasiveness, and disregard for personal space. If this feminist intention translated perfectly to viewers, then it’d be cut and dry to say Johnny Bravo wasn’t problematic at all.

In fact, some still celebrate the cartoon for its satire. The Odyssey even called Johnny Bravo a feminist cartoon due to its mockery of chauvinism: “…Instead of simply being an awful person, Johnny is just a guy who doesn’t know any better. He’s an idiot and his sexist tendencies are from his inability to understand that women typically don’t appreciate being called ‘hot mama’ by strange men. So feminism here comes from making fun of misogyny. Johnny never succeeds in his attempts to woo a lady because he treats them like objects to be won over by flexing muscles.”

Johnny Bravo – Talk to Me, Baby (Clip)youtu.be

But while its creator Van Partible designed the show to mock Bravo’s shortcomings, the art of satire is usually lost on children. Media critic Lindsay Ellis vows that Johnny Bravo was her favorite childhood cartoon, but as an adult, she critiques: “Problems arise because oftentimes the endearing aspects of characters like Johnny obfuscate whatever satirical critique they were supposed to represent (see Homer Simpson, Archie Bunker, Eric Cartman, Glen Quagmire, Rick from Rick & Morty, Tony Montana, Jordan Belfort from The Wolf of Wall Street).”

For context, Johnny Bravo was one of Cartoon Network’s earliest and most popular shows; it was one of the top five programs of the first network to run cartoons on a 24-hour basis. Clearly, kids watched the shit out of this satirical feminist program. But despite its intention, most kids grew up simply seeing a fun and hunky character who happened to be a funny and sympathetic chauvinist, rather than a mockery of one.

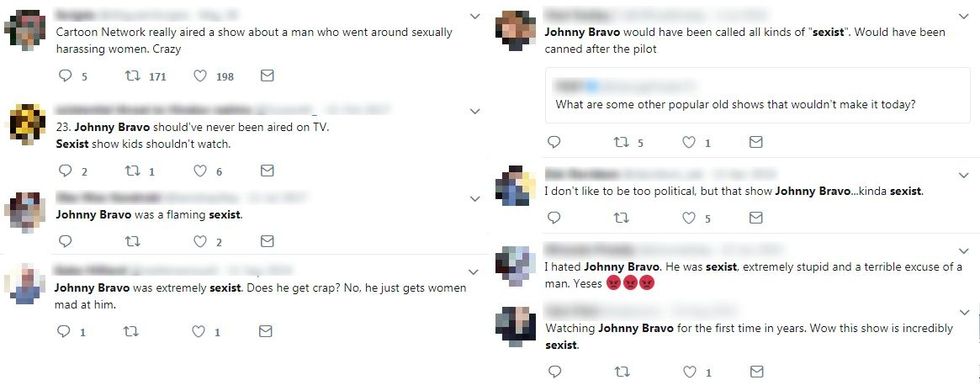

So now, we qualify our childhood love of the show. More pointedly, many bring attention to the character as a touchstone example of toxic masculinity, a concept that, while existent, was hardly spoken of in the ’90s. In fact, the term “toxic masculinity” was barely mentioned online until 2015, when it entered mainstream culture, and the #MeToo movement pushed conversations about toxic masculinity to popularity, from daily news and think pieces to sociological studies of workplace attitudes and, of course, media.

Twitter via LADbible

Twitter via LADbible

Case Study #3: Speedy Gonzales and Re-appropriating Stereotypes

Cartoon Network

Cartoon Network

On the other hand, rather than ban or openly criticize a stereotype, you could lean into it until you’ve effectively reclaimed and rebranded it as an icon of progressive diversity. Wait, what?

A go-to example of an offensive cartoon is Looney Tunes‘ Mexican mouse Speedy Gonzales, which was taken off the air in 1999 after it was deemed offensive. Cartoon Network’s Laurie Goldberg commented back in 2002, “It hasn’t been on the air for years because of its ethnic stereotypes. We have such a huge library, I think we intend to go with popular shows that aren’t going to upset people. We’re not about pushing the boundary. We’re not HBO. We have a diverse audience and we have an impressionable audience.”

As a reminder, Speedy wore a white smock, red kerchief, and an oversized sombrero, while the entire basis of the cartoon was Speedy’s attempt to cross the US border in order to steal the cheese guarded by Sylvester the Cat. His catchphrases “¡Andale ¡Andale!” and “¡Arriba ¡Arriba!” interpolated the character’s thickly accented English, which was never once voiced by a Mexican actor.

But, surprisingly, Speedy Gonzales was also popular in Mexico—according to Mexican filmmaker/actor Eugenio Derbez. The acclaimed actor told Deadline. “In Mexico, we grew up watching Speedy Gonzales. He was like a superhero to us, or maybe more like a revolutionario like Simon Bolivar or Pancho Villa. He watched out for the little people but with a lot of bravado and a weakness for the ladies.”

In 2016, Warner Bro. developed plans to create an animated feature film based on the character to be voiced by Derbez. On being the first Mexican actor to ever voice the character, he said, “I’m really excited to be bringing this character to the big screen. And besides being Mexican—my full name is Eugenio Derbez Gonzalez and I have big ears. The casting couldn’t be better.”

Progress on the film has since been stalled. General reactions to a Speedy Gonzales film have been divided between celebrating the mainstream representation it would bring the Latinx community and condemning the character’s damaging stereotypes. The Guardian noted the possibility that “it’s more racist to tell Mexicans what they should be offended by than to do a silly Mexican accent,” citing that “an actual Mexican in the lead role” could change the cartoons’ implications. Considering the League of United Latinx-American Citizens actually petitioned the Cartoon Network to bring the cartoon back in 2002 (which it did), there’s actually a chance that “the fastest mouse in all Mexico” could be re-appropriated by the Latinx community as a positive icon.

As a culture, we respond to problematic art by acknowledging its context and intention but then vehemently arguing about what to do about it. As adults, we can recognize the impropriety that defined the media of our formative years—from banningHappy Tree Friends for its graphic violence to finally discussing how Johnny Bravo perfectly exemplified toxic masculinity. Our primary responses seem to be to ban it, re-brand it, or lean-the-fuck-in because everything can be mocked until it becomes a satire of itself. That’s the power––or danger––of art.

POP⚡DUST | Read More…

Now in Theaters: 5 New Movies for the Weekend of May 10th

How Black Drag Queens Invented Camp: An Incomplete History of Lena Waithe’s Jacket

Has “Game Of Thrones” Lost Its Ability to Write Female Characters?

- 9 Cartoons You Didn’t Realize Were Racist & Totally Inappropriate … ›

- The 50 Greatest Adult Jokes Hiding In Kids’ Cartoons | Fatherly ›

- Dirty, Adult Jokes in Kids Shows ›

- 27 Adults Jokes In Cartoons That You Totally Missed As A Kid ›

- 21 Dirty Jokes In Nickelodeon Cartoons That You Totally Missed As … ›

- Most Inappropriate ’90s Cartoon Characters | ScreenRant ›