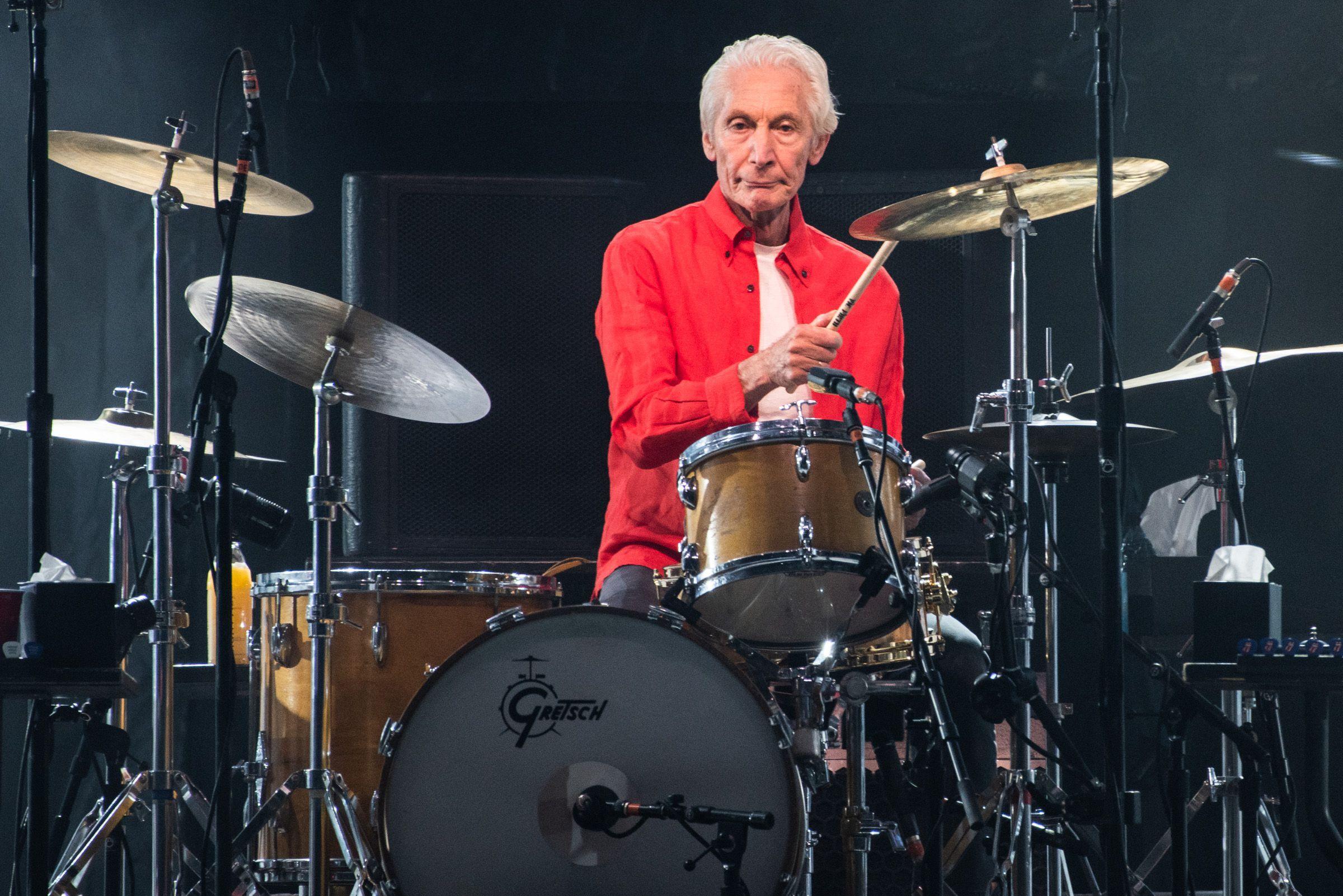

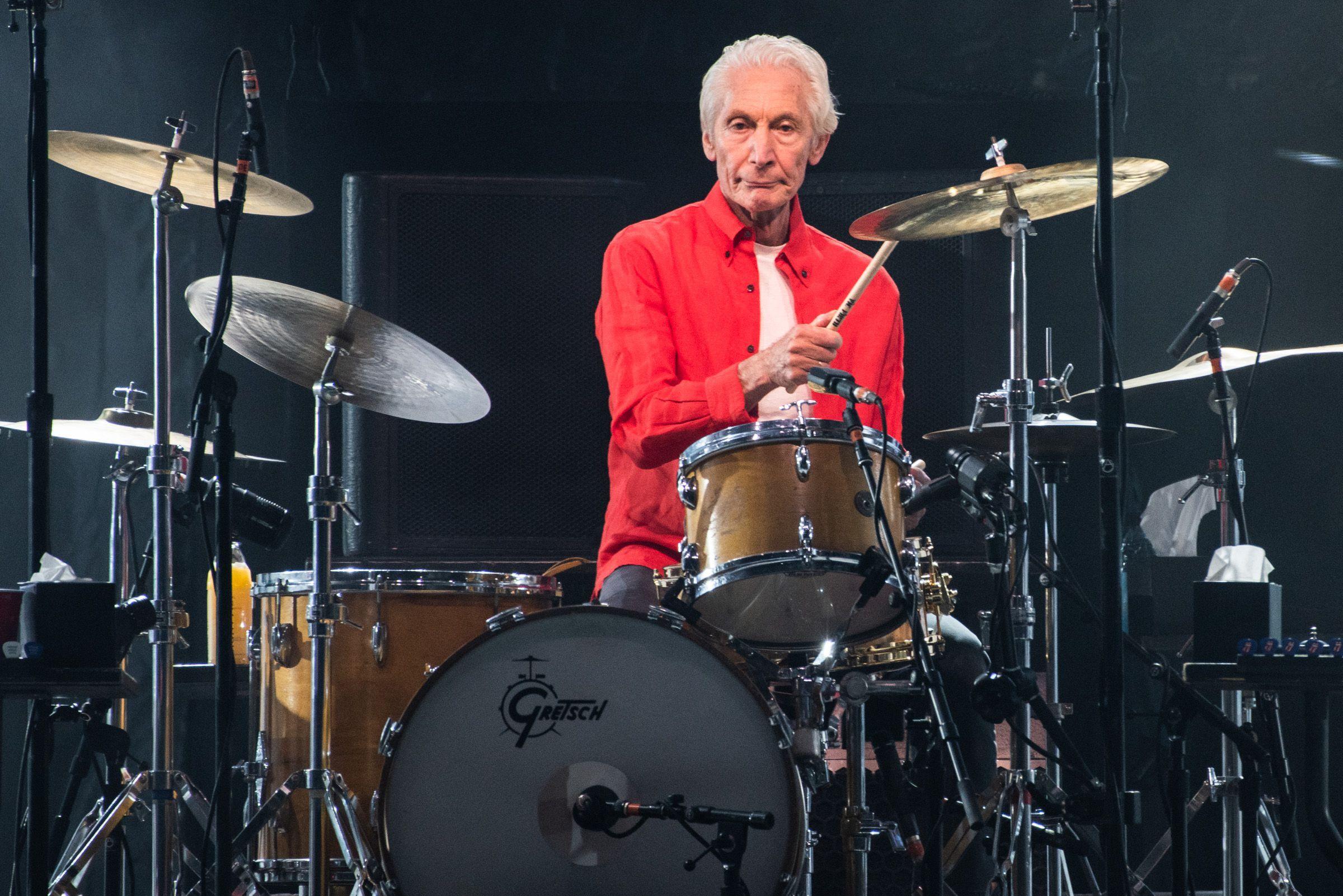

Charlie Watts was an unlikely Rock Hero.

A dapper, circumspect jazz aficionado who was married to Shirley Watts for almost sixty years, a family man who retired to his hotel after a concert to sketch – he’d been a commercial artist before joining the Stones – Watts didn’t live a typical rock star’s life. Nor was he a flashy drummer. Like his contemporary Ringo Starr, he eschewed bombastic displays of rhythmic prowess (a la Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham) and never indulged in sloppy theatrics (think of The Who’s Keith Moon).

All the same, though: Watts was a Rock Hero.

If you don’t believe me, listen to just about any of the more than four hundred songs the Rolling Stones recorded over the years: “Carol” and all the other Chuck Berry numbers, or “All Sold Out” or “Sway” or “Tumbling Dice” or “When The Whip Comes Down.” As rock critic Robert Christgau once noted, when those drums and guitars go into action, it’s the very definition of Rock and Roll.

Working with rhythm guitarist Keith Richards, Watts kept the juggernaut that was the Rolling Stones driving forward, ever forward, propelling the group from country honks to the White House lawn with ease and dexterity. You could call him the Gary Cooper of Rock and Roll – a quiet, self-effacing figure, not given to speechifying or bragging. But when High Noon arrived and you strode down Main Street headed for the shootout, you’d want a man like that by your side. The Stones had a man like that for two-dozen albums and countless tours.

Earlier this month Watts had gone into the hospital for “a medical procedure” – though what exactly that procedure was no one knows. In the 1980s he survived a bout of throat cancer and dealt with drink-and-drug issues. But one always assumed he’d be around, waiting patiently for the rest of the band to get down to business. In 1986 a reporter famously asked Watts what it was like working with the Stones for twenty-five years. Watts corrected him: he’d only worked five years, he said, with “twenty years of hanging around.” Such is the lot of a Rock and Roll Drummer.

Charlie’s death raises the question: Should the Stones stop rolling? They didn’t when founding member Brian Jones drowned in 1969; they replaced Mick Taylor, Jones’ replacement, with Ron Wood; and when Bill Wyman, the original bass player, retired, they replaced him, too. The Stones could easily find a new drummer and continue onward.

But things feel different now. Mick and Keith are in their late 70s and both of them have experienced age-related health problems. They have nothing left to prove; the Stones long ago earned the soubriquet of “the world’s greatest Rock and Roll band.”

It was Charlie Watts who put the “roll” into the group’s music. The rhythm section of a band is its heartbeat, its motive force. Without Charlie, Keith is missing the other half of the equation. It might be time to gracefully exit the stage.

Which isn’t likely to happen.