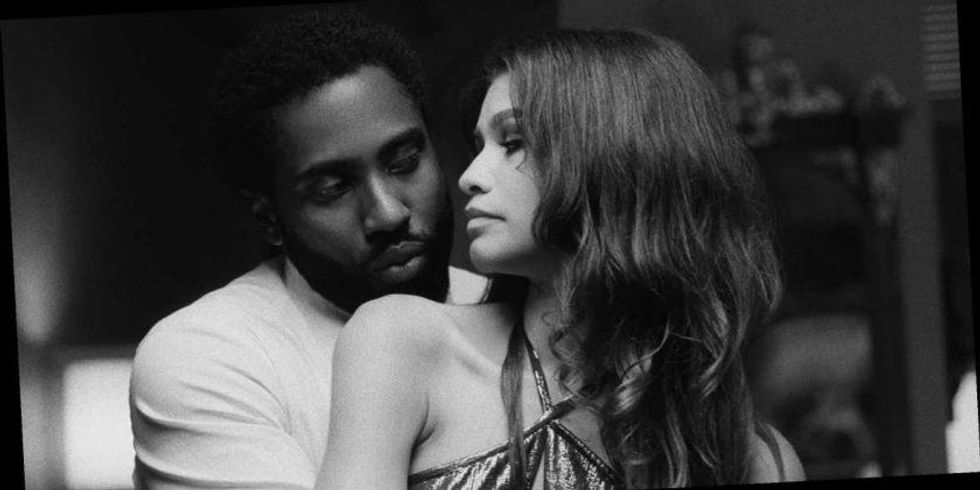

Zendaya and John David Washington in Malcolm and Marie

via Netflix

The new Zendaya film has been met with mixed reviews but there’s more than meets the eye in the long drama of Malcolm & Marie. Let’s unpack.

Malcom & Marie was born as a quarantine project by Zendaya and Euphoria creator, Sam Levinson, when the HBO show’s production was paused due to the pandemic.

The pair wanted to create something together, something that didn’t merely work around the filming restrictions but used them to its advantage. After throwing around ideas and looking through drafts of scripts, they decided on Malcolm & Marie, an ambitious project that takes place over one night in one place and that was shot by a small team of 22 over 14 days.

For Zendaya, the film was a risk. Though it was bought by Netflix due to her superstardom and John David Washington’s blockbuster status post-Tenet Tenet and BlackKklansman, the film draws plainly from the classics, the greats it aspires to emulate.

Throughout the film, Washington’s character, Malcolm, semi-pretentiously parades his knowledge of classic films and directors, and the movie itself mirrors the form. Notably, it’s shot in black and white and is the kind of movie that feels like it was adapted from a play. It’s already been compared to stage plays like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and even Fences (the film adaptation starred Viola Davis and Denzel Washington who played John David Washington’s father.)

Although Malcom & Marie debuted after Zendaya’s Euphoria Emmy Award, it was conceived before she secured her Emmy-winning pedigree. So, the actress still felt like she had something to prove, a more seasoned self to step into. This is her first major role as a leading lady and her first adult part (rather than a teenager).

In an Instagram post before the film’s Netflix premiere, she wrote: “Normally I’m pretty self-critical and that leads me to be far too fearful to make things myself or trust myself enough to even try. This is really my first time believing that maybe I could. This is my first time being a leading lady, but also my first time being this creatively involved in something, producing something, co-financing something, owning something, and sharing it all with my crew.”

What Goes Down in Malcolm & Marie

The film is an intimate endeavor that reveals a series of arguments that play out over one night and explores a couple at their worst. Washington plays a young director on the night following his first big premiere as he waits for what he expects will be fantastic reviews. The problem: He forgot to thank his girlfriend, Marie, on whom the film was ostensibly based.

Right from the gate, the film sizzles with tension, even as the couple goes through mundane tasks.

The first fight begins over mac-n-cheese, a slightly comical fact that’s over-emphasized, but nevertheless sets up the viewer for what the film will be: a battle of wills, an unflinching exploration of the ugly.

It all begins over the mac-n-cheese!via Netflix

It all begins over the mac-n-cheese!via Netflix

Some moments, admittedly, feel indulgent. It’s formidable to cram this much narrative into 2 hours. There’s not enough time to get to the heart of such complicated characters, let alone this relationship, let alone one as tumultuous as this. Instead of deeply investigating their personhoods, the film relies on hackneyed tropes: Marie, the recovered but bitter addict, and Malcolm, the braggadocious but insecure artist.

Despite the hype, the marketing, and the superstar actors, Malcom & Marie is not for the faint of heart. It draws out each harrowing beat over the course of two hours and forces the audience to feel it all without letting them look away.

Zendaya holds the movie togethervia Netflix

Zendaya holds the movie togethervia Netflix

Calling It Now: There Will Be Oscar Nominations

While the script is in need of more nuanced character development, the actors take potentially stale characters and build an entire world. Zendaya is unflinching and dynamic, as gentle and generous to Marie as Marie is to Malcolm.

Washington’s physicality is incredible. His wild gestures play his emotions in his whole body — from jumping on windowsills to taking out his aggression in the empty backyard. His larger-than-life performance, which draws from the character’s penchant for the dramatic and performative, is the perfect compliment to Zendaya’s control.

Washington counters her coldness with brash cruelty but meets her in the tender moments, too. He’s fine at putting on the bravado, but also fine portraying his shame.

Yet through it all, the focus is always on Zendaya. Though flawed and hurtful in her own right, Marie is the center of the film, bringing the conversation back and restarting the fight after its (sometimes overly contrived) pauses and breaks.

Sometimes, I wanted Marie to do more than smoke a cigarette in yet another outfit change because the moments where Zendaya simply sits and a medley of emotions shifts across her face are the film’s most powerful and most convincing.

We’re calling the Oscar nomination now — and not just because a film about film, about Hollywood and filmmakers and art, is always prone to industry recognition, but because these actors make this movie, keep you watching, and keep raising the tension well after you think they can.

What’s the Take Away: It’s a Love Story. But Not a Romance.

They say the meat of a movie is in the details, the little things that don’t seem to be about the plot but add so much and give so much away. In Malcolm and Marie, it’s the dress, the opening dialogue, the damn mac-n-cheese.

The whole night starts with Marie avoiding a fight, saying presciently: “Nothing productive is going to be said tonight.” She’s wrong, but the most productive things are said by her.

Just as she’s the dramatic center, Marie is also the moral center of the film. She’s not self-righteous and she’s not always in the right, but she counters Malcolm’s own self-satisfaction, self-indulgence, and self-absorption with an unwavering challenge and finally the insistence that he thinks about her.

“Once you know someone is there for you, that they love you, you never think of them again,” she says, and Malcolm’s whole facade of bravado falls down.

Malcolm & Marie explores the dynamic of a relationship built on trauma and feelings that go unaddressed, while pulling out the universal need to be acknowledged, seen, and appreciated by the people you love.

The film feels close to the wound, and much of its press has focused on the parallels between Malcolm and Sam Levinson. Much of the catalyzing action comes from Levinson’s life: his own experience with addiction, his own struggle with his representing both his pains and his privileges, and a moment where he too forgot to thank his wife in a speech.

The culminating monologue ties together the film’s broader themes of art and intimacy in a way that feels smart and sharpens the perspective on the whole film. Marie talks about the mystery of a relationship that mirrors Malcom’s reverence for the mystery of film.

via Netflix

via Netflix

Not a Film About Race … But Not Not About Race

Malcolm insists that his film is not it about race. “It’s a film about shame,” he says. “About guilt.” Both things become true for Malcolm & Marie.

“Cinema doesn’t need to have a message,” he later says in his epic physical rant about art and interpretation. “It needs to have a heart and electricity.” Malcolm & Marie has electricity, but it also has a message.

From the beginning, it has a keen eye on race and the white gaze. Between their arguments, Malcolm and Marie talk about the critics, the impending reviews, the “white girl from the LA Times” whose review later shows up to confirm Malcolm’s fears that his art will forever be evaluated through a political lens.

Many Black artists and filmmakers have expressed this same sentiment in their press tours — Jordan Peele, for example, made the distinction between Get Out, which was a commentary on racism, and Us, which was just a horror film that happened to center Black people, not a commentary on Blackness; and the recent Michaela Coel award snub forces us to ask whose stories get to be considered “universal?” Critics have wondered if Sam Levinson is allowed to use Black actors to make this point.

” Levinson, a white director, uses Malcolm as a black shield for his real target, not the critics who analyze Black works, but the ones who interpret his,” says the Guardian, and many critics have agreed. The film pulls no punches from its criticism of criticism, which makes those sections an easy target for critics.

But this is an easy target. The film doesn’t position itself as the authority on criticism, and Malcolm himself (maybe Levinson’s stand-in) is not safe from criticism (despite his desire to be) — not from the “white girl at the LA Times” and not from Marie. The film uses Marie to counter and challenge his self-protective rant against criticism, which does seem to hide a director’s own insecurity — but if that reflects Levinson’s own, he doesn’t paint himself a hero.

The conversations about race don’t come to conclusions about Blackness or art; they offer up ideas and prioritize the characters rather than their opinions. The characters are flawed, but they are not trying to get to the bottom of racism in one night. The film gives the characters room to be as complex and open about racism as it does about gender and art and anything else — resisting the idea of a monolithic opinion that all Black people share that can be defined.

Though this is a Levinson production, both Zendaya and Washington are producers with large creative influences on the project. As actors with agency, it would be reductive not to consider their own input must have made its way into the portrayal of Blackness in the film. And if Levinson and Zendaya had created this project, one of a Black director talking about reviews without talking about race, it would have been ignorant of the moment, the reality. Levinson speaks to current concerns but offers up complex viewpoints in response.

The film, ultimately, offers up that it is important to consider who is behind the scenes telling which stories, but it also says that artists are supposed to “imagine what life might be like for other people.” That imagination comes with internal scrutiny, as well as external scrutiny. What Sam Levinson’s whiteness shows is his confidence that he can tell any story, that he can start any conversation.

And white people should be having these conversations. They shouldn’t be the authority on what representation means, but they should examine its limits and be open to the criticism they might receive. A film this commercial should allow entry into the conversion and force white audiences to ask themselves how they think and talk about race, representation, and their own supposed wokeness — Levinson included.

What Malcom & Marie has the potential to do is normalize the interplay of talking about race in a film without making it a “race” film that gets ignored by mainstream audiences and preaches to the choir. The commercial marketing of the film should embolden Black writers to be as unapologetic as this, to make a movie as capacious and ambitious as this but more refined — and without spending this much time justifying it.