Kojima Productions

*MAJOR spoilers for Death Stranding follow.*

After clocking over 60 hours in Death Stranding, I can comfortably say that I had almost no fun playing any of it.

I can also say that, after nearly three decades of gaming, Death Stranding was one of the greatest, most revelatory video game experiences I’ve ever had. No, those two points are not contradictory. Allow me to explain.

A Game That Defies Its Medium

Movie buffs don’t seek out The Deer Hunter because they expect to have fun watching it. Literary enthusiasts don’t keep the Russian classics alive because they’re amusing reads. Anime fans don’t continually analyze Neon Genesis Evangelion because it’s an enjoyable series. With every other artistic medium, audiences understand that while some works are meant to be fun, others are meant to be intellectually or emotionally challenging. But with video games, perhaps due to the interactive nature of the medium, fun still prevails as the loftiest goal in most people’s minds—myself (usually) included.

When I think back on my favorite games over the past few years, Mario Odyssey stands out as one of the highlights. Odyssey is rich in creative level design, novel mechanics, and innovative gameplay that pays homage to everything gamers love about the Mario franchise while constantly keeping the experience fresh. Playing Odyssey makes you feel like a child who was just handed an overflowing toy box and given permission to go wild. I played it to 100% completion with a big, dumb grin on my face the entire time (with the exception of the jump rope minigame…damn you jump rope minigame). Of course, there’s hardly any narrative beyond “Rescue Princess Peach!” but a Mario game would only get bogged down by anything else. The entire goal is to have fun playing. In a sense, Death Stranding is the polar opposite of Mario Odyssey.

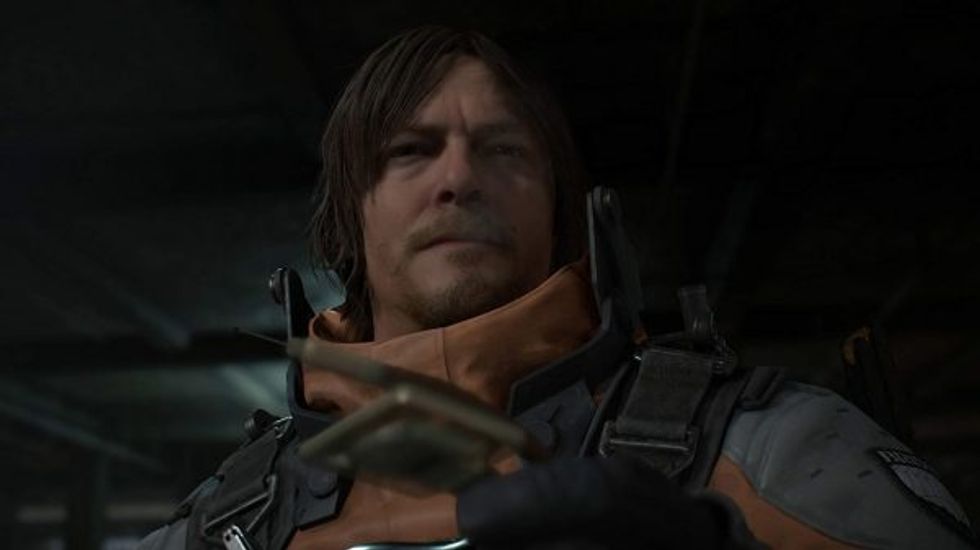

But Death Stranding never presents itself as a traditional video game. Created by Metal Gear Solid auteur Hideo Kojima as his first release after breaking up with his career-long publisher, Konami, even the marketing for the game centered entirely around the bizarre, star-studded cinematics and inherent mystery surrounding its visuals. Featuring Norman Reedus and Mads Mikkelsen, alongside supporting performances by Guillermo Del Toro, Léa Seydoux, and Margaret Qualley, Death Stranding exists in a bizarre subspace between movie, video game, and something else entirely.

A Game That’s Not Fun to Play

Set in a post-apocalyptic America, the plot of Death Stranding follows Norman Reedus’ Sam Porter Bridges, a porter with aphenphosmphobia (a fear of being touched, both physically and emotionally) who carries packages for a government organization called Bridges led by his mother, President Bridget Strand. With humanity all but wiped out, civilization hinges on a few remote waystations, bunkers, and prepper outposts. Bridges tasks Sam with connecting all of these stations to the “chiral network”—a supernatural, high-tech Internet of sorts—meaning that Sam must travel across America on foot, delivering supplies and convincing preppers to share their information with the government. As any fan of Kojima’s work already knows, the plot gets mind-numbingly complicated, but that’s the basic premise.

The core gameplay of Death Stranding is walking across vast stretches of barren, oftentimes gorgeous terrain, packages in tow. As Sam Porter Bridges, every rock and bump on the ground is a fresh obstacle to stumble over, with the threat of hard, cargo-damaging falls hanging over your every step. Your shoes and equipment degrade as you trek across the wasteland. You constantly check the weather to avoid “Timefall”—contaminated rain that speeds up aging for anything it touches. Power-ups come in the form of more advanced equipment that allows you to carry more weight or cling to hillsides a little bit easier, but none of it ever changes the careful, difficult manner in which you’re forced to move throughout the world whilst lugging heavy packages. If that sounds grueling and tedious, well, it is.

There are enemies, too, in the form of MULEs and BTs. MULEs are other porters who have lost their minds and now troll around encampments in the wilderness waiting to steal packages from any porter unfortunate enough to enter their territory. BTs, on the other hand, are supernatural ghost-like creatures which loiter in the air, waiting for you to get close so they can pull you into otherworldly pits of black tar (wherein giant BT animals attempt to kill you and, more pressingly, ruin your packages). You’re given weapons to deal with both of these threats if necessary, but no matter how much you upgrade your bullets, the battles are long, fraught, and stressful. Avoidance is always the easier approach.

Then there’s Lou, your BB, or bridge baby, which is essentially a baby in a pod who can sense BTs. The narrative presents BBs as a tool, not to be mixed up with real, living babies, but that doesn’t stop Sam (and by proxy, you) from forming a genuine connection with Lou as the only two sentient beings traveling together for miles and miles. Lou coos when you run quickly or escape a tense scenario and blows heart-shaped bubbles to show affection. Lou is also an ever-present consideration during gameplay. If Lou gets too stressed, then he’ll enter a comatose state called autotoxemia, and anytime you take a tumble or get hurt, Lou will start crying, which echoes loudly from your controller. To soothe him, you need to manually detach his pod from your suit and gently rock the controller back and forth.

But while one might think that gameplay would be more stressful with a crying BB attached to their chest 24/7 than without, Lou is taken away from you for an extended period of the game, which ends up being an absolute nightmare to deal with—partially due to your inability to detect BTs, but also due to the feeling of loneliness that sinks in as you hike snowy mountain tops with your only traveling partner absent. Therein lies the reason why Death Stranding so deeply affected me, perhaps more than any other game I’ve ever played.

A Game With a Powerful Theme

Death Stranding breaks you down through boring, repetitive, yet challenging gameplay that requires constant attention. Once you’ve mastered the basics, the gameplay loop inspires a borderline meditative state, wherein you’re forced to reflect upon the very concept of walking in a video game. What is the purpose of playing a game like this? Is this even a game?

Death Stranding opens with an excerpt from surrealist Japanese author Kobo Abe’s short story, “Nawa”:

“The ‘rope,’ along with the ‘stick,’ together, are two of mankind’s oldest tools. The stick to keep the bad away, the rope used to bring the good toward us. They were our first friends, of our own invention. Wherever there were people, there were the rope and the stick.”

Everything in Death Stranding, absolutely everything, revolves around the theme of humans choosing to connect with one another instead of driving each other away. But Kojima isn’t content with players simply recognizing that theme. He wants them to experience it for themselves. Every element of Death Stranding is intended to put players into Sam’s headspace as an antisocial loner, and ultimately find comfort through human connection—not just through the narrative but through the actual gameplay.

In a lot of ways, Death Stranding is less a video game and more an indefinable work of participatory art. It would be impossible to talk about the merits of Death Stranding without delving into the deeply personal experience of playing it, and yet, so many of those experiences are so minute that they’ll undoubtedly sound absurd to anyone who hasn’t played it themselves.

For example, some of the tools at Sam’s disposal include ladders, climbing anchors, and bridges, which Sam can set up to help scale particularly difficult ground. Then, assuming you’re playing online, whenever you bring a local waystation onto the chiral network, the structures that other players have built will appear for your use, too. When you use one, or if you happen to be feeling kind, you can award that player with “Likes”—which have very little practical in-game use.

But alongside immediately useful tools like ladders, players can also construct seemingly useless signposts displaying emoji-like symbols including smiley faces and thumbs ups. When the concept was first introduced, I immediately thought it was stupid—or more specifically, “Who would ever use these?”

A little later, I was tasked with delivering packages to a remote weather station nestled atop a steep mountain. Throughout the course of my slow, arduous climb, I was caught in a heavy Timefall and attacked by BTs. With packages degraded and shoes worn out, I barely managed to escape their ghostly tar pits. Finally I reached the station to make my delivery and bring them onto the chiral network. Then it dawned on me—I couldn’t actually rest at an outpost. Before I could properly recover my energy, I’d need to make it all the way back to a proper hub, back through the rain, back down the mountain. The dread felt so real. But as I reached the top of the first rough peak to begin my long descent, something caught my eye. Someone had posted a thumbs up sign.

A warm sense of comfort immediately washed over me. I wasn’t alone. Someone else had been here, another human being. They had conquered this trial, and they left this sign to assure me that I could do it, too. There was no logic to my response; it was entirely emotional. I awarded the thumbs up sign the most Likes I possibly could, and from then on, whenever I topped a particularly challenging peak, I left a sign, too. Every so often, the game would notify me that someone else liked a sign I set up, and I couldn’t help but feel like I was part of something larger than myself.

And then there are the moments where, at the height of a horrible trek, you catch sight of a breathtaking mountain vista rendered with some of the most photorealistic graphics you’ve ever seen in a video game. Or you hit the bottom of a slope, the next hub just on the horizon, as a haunting Low Roar song begins to play (seriously, the soundtrack is incredible). These moments are fleeting, profound, and wholly beyond words. The world may be empty, but you’re not alone. Even at the end of the world, there’s still beauty, and there are still people on the other side. Kojima instills these views in us not through telling or demanding, but by leading us to understand for ourselves…and then he puts what we’ve learned to the test.

A Game With a Greater Point

***MASSIVE ENDGAME SPOILERS FOLLOW

Author’s Note: Before proceeding, please, please, please ask yourself whether or not you ever plan to play this game. As a lifelong gamer, I’m confident that going into Death Stranding with as little knowledge as possible is truly one of the greatest experiences possible. It’s not too late to turn back.

If you’ve already finished the game, or really never plan on playing, please proceed.***

The final confrontation in Death Stranding will forever stick with me as one of the most brilliant strokes of storytelling and game design imaginable.

Upon completing your task and reconnecting America, Sam is faced with horrifying reality that his mother, Bridget Strand, is an Extinction Entity—a being whose entire purpose is to bring about a massive global extinction event (this makes more sense in context of the larger plot). Bridget hands Sam a gun and tells him that he has two choices. Option one: Sam can shoot her, potentially stopping the destruction she’s already set off, but with the caveat that he’ll be trapped forever on her interdimensional Beach (this also makes sense in context of the larger plot). Option two: Sam can do nothing, spending his last few moments with his mother as the world ends and knowing full-well that if it doesn’t end now, then it will end eventually.

You resume gameplay with the gun drawn. You have six bullets. Bridget slowly walks from the Beach’s sandy bank towards the horizon, where a giant, apocalyptic ball of destruction looms in the sky. Clearly, the game expects you to shoot Bridget, but if you fire the gun at her, the bullets warp through her like she’s an apparition. As soon as you run out of bullets, you’re out of options. Tears of blood run from Bridget’s eyes as she rises into the sky. The world is over, and the game resets to the beginning of the confrontation.

I imagine that it takes most players a few tries to figure out what they’re missing. Why won’t the bullets work? Is there something else to shoot? Did Kojima hide something somewhere? The answer is no. You’re not missing anything. You’re just not thinking about the scenario properly.

After my own slew of failed attempts, it dawned on me: Death Stranding is all about connecting with people. Just like Abe’s quote in the beginning of the game said, the gun is the “stick.” In that case, what is my “rope?” I unequipped the gun and approached Bridget, causing an action prompt to appear: “Hug.”

Indeed, hugging Bridget in the face of armageddon effectively ceases the destruction of humanity. By connecting, by drawing people closer, we accomplish far more for humanity than we do by pushing them away. Hideo Kojima knows that every video game we’ve ever played has conditioned us to shoot when given a gun. Through setting up a scenario where the gun we’re given is useless, he forces us to utilize the lessons that he has attempted to instill in us throughout the entirety of the game.

If the average video game is a power fantasy that grants you superhuman skills and cool powers, Death Stranding feels almost like a de-powerment simulator. And yet, it all serves a thematic point. The emotional core of Death Stranding is conveyed so powerfully, so experientially, that it’s hard to picture any other medium providing anything even close. I didn’t have fun with Death Stranding, but I felt frustration and wonderment. I laughed occasionally, and I cried, too. Death Stranding connected me with other people I couldn’t even see, and I walked away with a deep sense of emotional fulfillment. Connection is everything, and I feel that in my core—that’s the beauty of Death Stranding.

- Death Stranding Review – IGN ›

- Death Stranding review: Is it worth the hype? – Polygon ›

- Metacritic deleted over 6,000 negative Death Stranding ratings ›

- Death Stranding Review: Bless This Mess | GQ ›

- Death Stranding review – Hideo Kojima’s radically tough slow … ›

- Dunkey’s ‘Death Stranding’ Review Is More Fun Than The Game ›

- Themes and artistic “fabric” of Death Stranding : DeathStranding ›

- Death Stranding Available November 8 on PS4 – PlayStation.Blog ›

- ‘Death Stranding’ creator says Trump, Brexit inspired game’s themes … ›

- What Hideo Kojima Wants You to Learn From Death Stranding | Time ›

- Death Stranding is Hideo Kojima’s take on Internet toxicity. And his … ›

- Death Stranding for PlayStation 4 Reviews – Metacritic ›

- Death Stranding review: both breathtaking and boring – The Verge ›