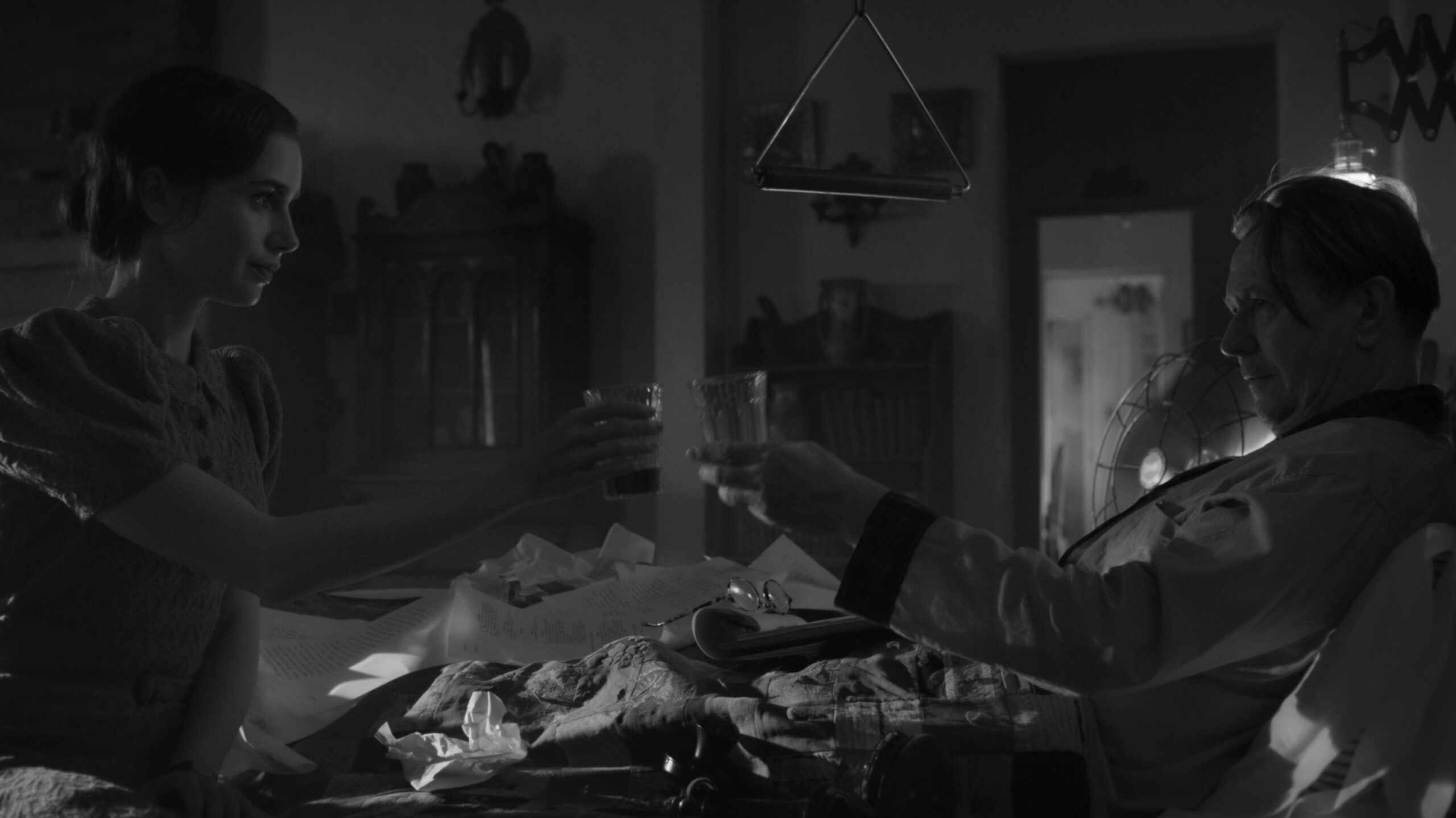

Lily Collins and Gary Oldman in "Mank"

Update 3/15/2021: Oscar nominations have just been announced, with Mank receiving a total of 10 — more than any other film this year — with nominations for Best Picture, Best Director (David Fincher), Best Actor in a lead role (Gary Oldman), Best Supporting Actress (Amanda Seyfried). The film also received well-deserved nominations for Cinematography, Production Design, Costume Design, Sound, Score, and Makeup.

David Fincher is not a director known for pulling punches.

In movies live Seven, Fight Club, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, he has demonstrated a willingness to linger on scenes of horrifying gore and violence.

Studios often discourage this kind of spectacle, as it relegates movies to an R rating and the smaller audience that entails. But in Fincher’s case — with the notable exception of The Social Network — he has managed to build a career on it. So it’s strange to note that the film he has spent more than 20 years fighting for had entirely the opposite problem.

Events at the Margins

Most of the drama of Fincher’s brilliant Mank — which became available on Netflix on December 4th — is subdued, quiet, removed from view. At what may be viewed as Mank‘s most pivotal moment, the sound of a gunshot rings out. Muzzle flare flashes in a distant window.

It’s emblematic of a film that revolves around a man who could be viewed as one of history’s background characters — with towering figures of the era looming around him — a film that pays homage to the cinematic style of the 1930s and ’40s.

The film follows screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), AKA Mank, as he works on the screenplay for Citizen Kane in 1940. An oft-uncredited writer whose approach to storytelling relied heavily on snappy, stylized dialogue, Mank was “always the smartest guy in the room” — sometimes to his detriment. He was an alcoholic and a compulsive gambler who spent those months he worked on Citizen Kane bed-ridden with a broken leg.

MANK | Official Trailer | Netflixwww.youtube.com

Outside, World War II was raging across Europe, and America was at a political turning point as FDR’s New Deal programs pulled the nation’s workers from the nosedive of the Great Depression — against the opposition of wealthy elites. But in a small town in the Mojave desert, a man was lying in bed, working in secret to convert Hollywood gossip into a screenplay — and doing what he could to get his hands on some liquor.

Those major world events are there in the background as Mank plays out through snapshots and flashbacks. But dramatic content like a German U-boat attack, a car crash, a suicide, and a village of refugees being saved from the Nazis all happens off screen or at the margins — related through suggestion and through the film’s perfectly snappy and antiquated dialogue.

More than the use of black and white, or a notable visual reference to Citizen Kane‘s most famous shot, this style of hidden drama — and the proof that it can still be used to tell a compelling story — is how Mank pays tribute to its subject.

Prior to the advent of nine-figure special effects budgets, it was up to writers and directors to bring grand stories down to a human scale, and that’s where Mank flourishes. It tells an intimate story that manages to pull historic moments and grand figures into its orbit.

How Did Mank Get Made?

Much of that can likely be attributed to the director’s late father, Jack Fincher, who wrote the screenplay back in the 1990s. But what makes the movie so interesting is also what left it untouched for decades, only to finally get made now — when its messages on politics and the media are more pressing than ever.

It’s not a loud, exciting blockbuster. Nor does it quite fit the mold of tragic Oscar bait.

As in the 1940s, there are certain formulas that play well to studio executives and which audiences recognize. As Fincher put it in a recent conversation with Total Film, “There’s really only two seasons for movies. There’s ‘spandex summer’ and there’s ‘affliction winter.'”

In that context, how does a movie like Mank even get made? As it turns out, much the way that Citizen Kane did.

The opening text of Mank lays out the scenario for Citizen Kane. A struggling movie studio takes a gamble on a wunderkind, giving him carte blanche — “absolute creative autonomy.”

Orson Welles and Herman Mankiewicz use that leeway to great effect in creating a complex and timeless narrative attacking a powerful media mogul. It’s the kind of risk a more stable studio would never have bothered with.

In the case of Mank, Netflix executives gave David Fincher a similar freedom. After the end of his series, Mindhunter, they approached him with as broad an appeal as any director could hope for: “What do you want to do next? Do you have anything that you’ve always wanted to make?”

That apparently included the possibility of a passion project devoted to almost subliminal drama.

As David Fincher put it in an interview with The Telegraph, “What the streamers are doing is providing a platform for the kind of cinema that actually reflects our culture and wrestles with big ideas: where things are, what people are anxious and unsure about. Those are the kinds of movies that would have been dead on arrival five years ago.”

Hearst vs. Welles vs. Mankiewicz

While the film stands on its own merits, for those with an interest in this kind of behind-the-scenes information, there is a further layer of hidden drama. Orson Welles (Tom Burke) and William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) were two men with massive egos who faced off over Citizen Kane, and their conflict looms at the edges of Mank.

Hearst was an old and wealthy man who had already seen the peak of his success as a newspaper magnate and Hollywood producer — and was approaching the low-point of his downfall. Welles was a young upstart, a Hollywood outsider and a purported genius destined for greatness — and for a downfall of his own.

The battle between the two over the release of Citizen Kane — an unflattering portrait of Hearst which he fought to quash — is now the stuff of legend, but it’s only hinted at in Mank. We see the makings of that clash in fearful invocations of Hearst’s power from Mank’s brother, Joe (Tom Pelphrey), in Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) pleading on Hearst’s behalf, and in brief flashes of Welles’ notorious temper.

Neither of these men would end up getting what they wanted. Hearst’s reputation would forever be linked to Citizen Kane, while his effort to suppress it would permanently stunt Welles’ movie career.

The Parable of the Organ Grinder’s Monkey

In Mank we see the relative nobody who was Herman Mankiewicz — a washed-up, alcoholic gambler with a big mouth — push back against these domineering men who try to use him for their own ends. He calls out Hearst’s hypocrisy on a grand scale and clutches credit for his work from Welles’ egotism.

Following one of the movie’s guiding themes, Mank proves that he’s not “the organ grinder’s monkey.” He proves that his work is powerful — that he doesn’t have to dance to someone else’s tune.

Mank is a loving portrait that doesn’t mind bending the truth or fudging the details for the sake of a good story. As Mank himself puts it, “You cannot capture a man’s life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave an impression of one.” And Mank does an excellent job of that, with just enough of a basis in real Hollywood history to delight those who go looking for it.

Thanks to the freedom the streaming age has provided — and with the help of Gary Oldman’s brilliant performance as Mank — Fincher was finally able to bring his father’s decades-old screenplay to life. The result is a memorable and quietly gripping movie that major studios were too cautious to make.