Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith at the 'Aladdin' World Premiere

Photo by DFree (Shutterstock)

King Richard is an upcoming biopic highlighting society’s time-honored traditions of competitive sports, underdog victories, and discrimination based on skin color—wait, what?

The film’s speculative script by Zach Baylin details the work ethic and dedication of Richard Williams, the father of tennis legends Venus and Serena Williams. Despite having no experience in professional tennis, he began coaching his daughters when they were four years old and remains one of their professional coaches today. Will Smith is already attached to the film’s production, but this week, there’s speculation that Smith will star as the titular coach.

Cue people being irate on Twitter over Hollywood’s lack of representation. But what is there to criticize about a successful black actor playing the part of the most successful black tennis coach? In short, some argue that Smith is too light-skinned to play the much darker-toned Williams because doing so would imply that Williams’ story is only worth telling on screen if he’s whitewashed to a lighter, more “appealing” complexion. Sports writer Clarence Hill Jr. was among the first to take the issue to Twitter, posting, “Colorism matters…love Will Smith but there are other black actors for this role.” Writer George M. Johnson agreed, “Just like Chadwick [Boseman] shouldn’t have played Thurgood Marshall, Will should not play Richard.”

Many continued to question why a dark-skinned actor, like Mahershala Ali, Idris Elba, or Denzel Washington, isn’t being considered for the role. The criticism doesn’t target Will Smith’s acting abilities, but rather Hollywood’s part in perpetuating the privilege that Western society has always given to light skin tones. Among the talented black actors available, why not cast one who bears a more striking resemblance to the subject and counteracts Hollywood’s overabundance of light skin tones? Meanwhile, some think it’s squabbling to argue over a light-skinned actor being cast as a dark-skinned character. They wonder, as long as they’re the same race, what’s the difference? One user even commented in a since-deleted post, “So you know Will Smith is BLACK, right? This is reverse colorism.”

As quick as we are in our culture to call out racism, the issue of colorism is often subtler, more nuanced, and so deeply ingrained in our history and media that it can take an extra moment to explain. At best, the public backlash is intended to draw enough attention to an issue to enact social change; at worst, it’s just frivolous outrage added to the Internet void. In general, people need to calm down to begin any productive discussion about race and representation. But before we can de-escalate the tension surrounding the words “racism” and “colorism,” we need to shuffle closer to understanding.

To pull out the old Oxford English Dictionary, let’s agree to define colorism as: “prejudice or discrimination against individuals who have a dark skin tone, especially among people of the same ethnic or racial background.” To contrast, let’s put aside how fraught the word “racism” is long enough to define it as: “a belief that one’s own racial or ethnic group is superior, or that other such groups represent a threat to one’s cultural identity, racial integrity, or economic well-being.”

To be clear, many of today’s accusations of “racism” are more likely instances of “colorism.” The critical difference between the fallacies is that the latter over-values an entire racial group, while the former over-values light-colored skin in general. And no, contrary to the current wisdom of Urban Dictionary, colorism is not exclusive to black communities.

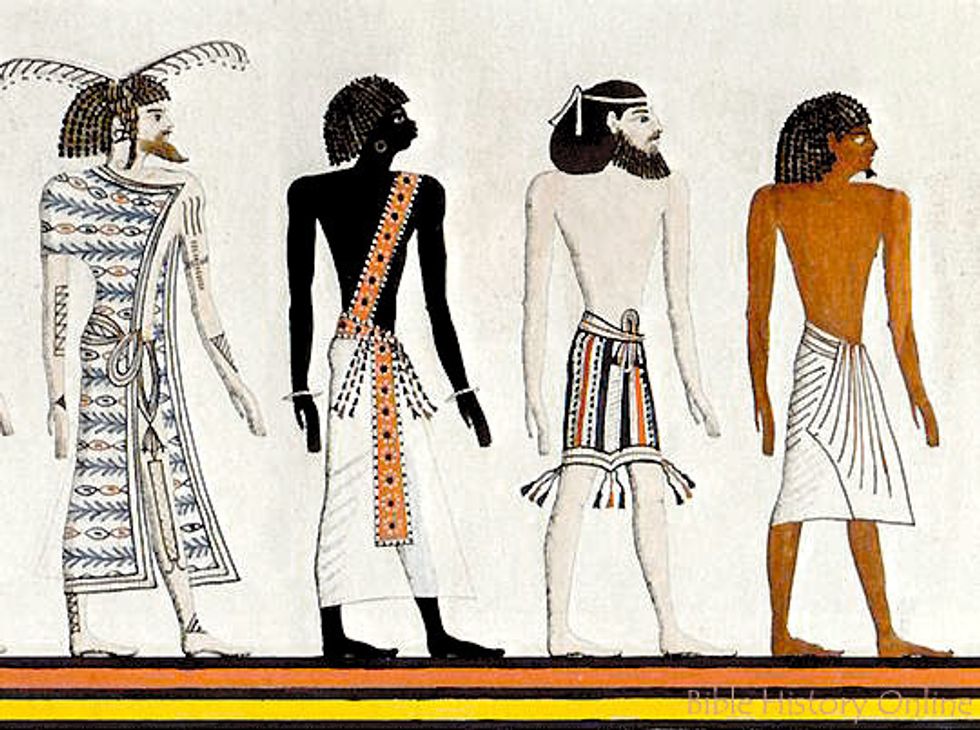

While no less discriminatory, colorism is, unfortunately, an older, deeply-ingrained tradition found in nearly all societies dating back to the Middle Ages. African and Latin American history is shadowed with the tradition of slavery thanks to ancient Judeo-Christian societies justifying human suffering by claiming that the biblical figure of Ham, the dark-skinned son of Noah, was cursed to be “a servant of servants” because of his skin color. In Asian cultures, especially Korean society, pale skin was revered as a sign of elite social status as far back as 2333 B.C.E. And let’s not forget that white people have been discriminating against other white people on the same basis. In northern Italy, there’s an old racist myth that southern Italians are of a darker (and so inferior) race than northerners. Even in Shakespeare’s England, one of the worst insults to a woman’s beauty was to say she was not “fair” (referring to skin tone). (As for Elizabethan men, well, the whole plot of Othello’s based on the assumption that dark-complexioned men aren’t to be trusted).

In modern media, those sentiments live on, even amidst Hollywood’s self-congratulatory banner of inclusion for people of color–even now, most casting is of those with lighter skin tones, whether they’re black, Middle Eastern, or Asian. Recently, Disney’s been accused of whitewashing Guy Ritchie’s live-action Aladdin, with only light-skinned Indian and Arab actors selected for Middle Eastern parts. In 2016, Zoe Saldana was cast as Nina Simone in the biopic Nina, with many speaking out against the fact that the light-skinned actress required dark makeup and a prosthetic nose for the part. Even Simone’s daughter expressed disquiet, commenting that Saldana was a capable actress, but “there are many actresses out there, known or not, who would be great as my mother.” She added, “My mother was raised at a time when she was told her nose was too wide, her skin was too dark. Appearance-wise, this is not the best choice.”

In other cases, companies have been panned for trying to reverse colorist beauty standards before the public was ready. Recently, Zara was heavily criticized for a Chinese ad campaign that featured a model with freckles rather than the porcelain white skin that dominates the Asian ad industry (“Asian women don’t have freckles!” one commenter said before claiming to boycott the company).

In terms of King Richard, would people be this upset if the role was given to a light-skinned actor who wasn’t a high-profile celebrity? Probably not. Inevitably, projects with greater name recognition are subject to closer critiques of the politics they imply. For instance, last year The Upside depicted a disabled man’s (Bryan Cranston) relationship with his caretaker (Kevin Hart). Vocal outcry pointed out that a physically disabled actor was passed over for Cranston because Hollywood doesn’t create opportunities for disabled actors. No one was panning Cranston’s performance (he is a talented actor, after all). Rather, the issue tapped into Hollywood’s persistent problem of underrepresentation.

So what do people want? Should actors like Will Smith be excluded from jobs they’re qualified for based solely on their light skin color? No; that would also be colorism (contrary to what some Twitter users believe, “reverse colorism” is just as nonexistent as “reverse racism”). The intention of the “colorism debate,” as the BBC called it, is to promote equal consideration and visibility of all skin tones in media. Inherently, this goal banks on public opinion gaining more influence over Hollywood decisions, which has begun with increased social media, crowdfunded projects, and the #MeToo movement being predicated upon empowering everyday individuals to sound an alarm against prejudice.

Still, the ultimate goal of equal representation in media is far off from the status quo. It’s a fact that there have been more white and light-skinned figures represented in media than non-white individuals. But we’re not equipped to collectively recognize continuations of that pattern, let alone to interrupt it until we can talk about “racism” and “colorism” using the same respect for history and a core understanding of what our words mean.

POP⚡DUST | Read More…

7 Movie Reboots We Deserve Before We Die

Fetishizing Autism: Representation in Hollywood

Welcome to Genderqueer TV: 5 Non-Binary Characters

- Eugena Washington talks success after ANTM, Playboy, and Social … ›

- 5 shows return to TV this summer you won’t want to miss – Popdust ›

- A Review Of Dear White People – Popdust ›

- Dear White People tackles race, sexuality, and identity – Popdust ›

- ‘Vida’ Shines a Light on Latinx Queer Women – a review – Popdust ›

- As If You Needed Another Reason to Love Idris Elba: Actor Launches $40M Coronavirus Relief Fund – Popdust ›

- 5 Insane Live-Action Disney Movies We Want to Actually Exist – Popdust ›

- White-Washing Isn’t Exclusive to Scarlett Johansson—5 Other Problematic Castings – Popdust ›

- How Asian Men Became Hot in Hollywood – Popdust ›