D-Crunch Backstage

By Nadeem Rahimi (Shutterstock)

The 7-member K-pop band’s latest single, “Butter,” has broken world records this past week, and I still don’t want to have kids.

For context, I mean I’d rather walk from my Brooklyn apartment to my midtown Manhattan office in my bare feet than be responsible for parenting a child. That being said, my aunt-game is incredible. My seven-year-old niece thinks I live in one of the fancy NYC skyscrapers she sees on TV, and my four-year-old niece thinks she’s Wonder Woman. What’s not to love?

The seven-year-old says she looks like me, which is pretty accurate. I mean, I have freckles and I’m taller. She has straight hair, and mine is wavy. But with our black hair, pale skin, and broad cheekbones we share a resemblance, despite not having a single strand of DNA in common.

Although my nieces are still working on the simple geography of their small suburb where I also grew up, I’ve mentioned that both their dad and I were born Somewhere Else called “Korea” (I can’t wait to explain that their dad is, literally, my brother from another mother).

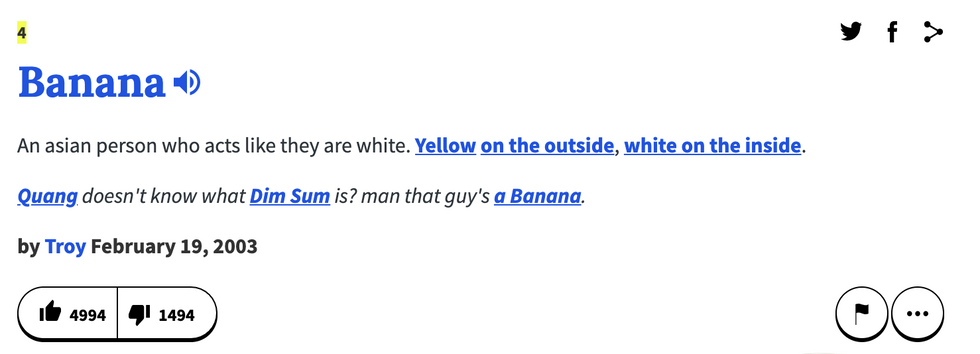

As they get older, we’ll get around to words like “adopted,” “naturalized citizenship,” and the grosser ones like “model minority” and “yellow face.” At some point, I’m sure “banana” will be revised, too: “Yellow on the outside, white on the inside.”

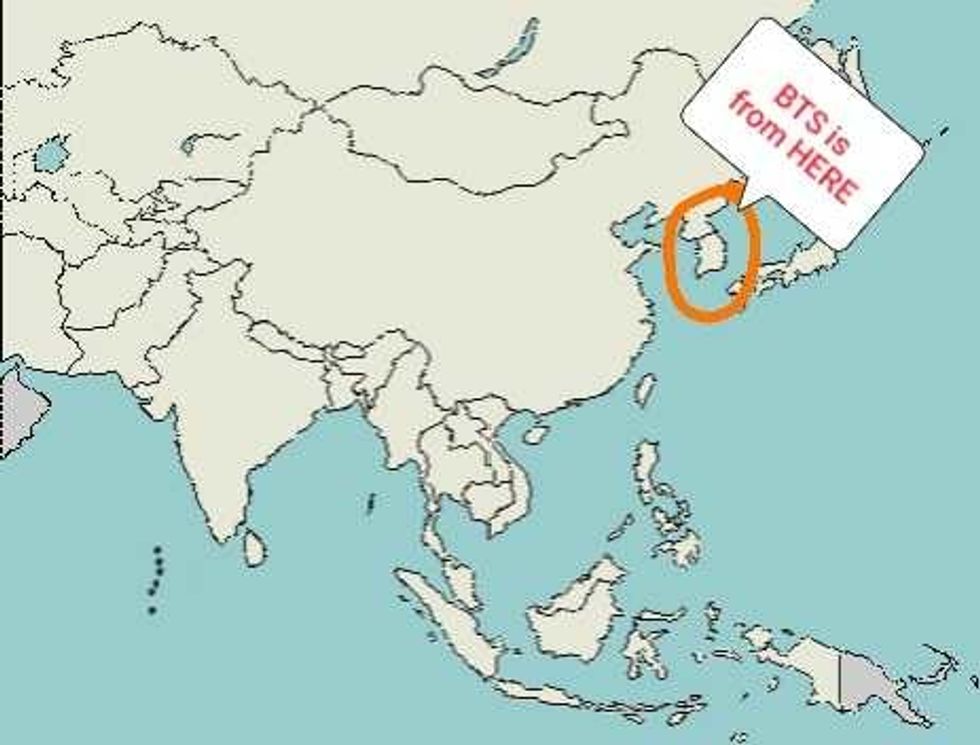

But for now, they certainly don’t know where Korea is… And these days I still wonder who actually does. Growing up in a rural, predominantly white suburb in the ’90s, everybody I met was like my nieces, in that they had no clue what or where Korea was. During standard education’s requisite five minutes of covering Asian history, this map was agonizing. Truly, take a guess where Korea is, I dare you.

But in the last 20 years, it seems every aspect of childhood has changed. Kids want to grow up to be YouTube stars (did you know some 10-year-old named Ryan makes $30 million a year by reviewing toys and yelling a lot on his channel?). Toddlers can ask Alexa to play “Baby Shark” until you shut off the Internet, and every toy ad these days looks like a diversity pamphlet compared to what I grew up with (RIP the unbearable whiteness of ’90s candy commercials).

But of all the cultural differences that demarcate my childhood from that of my nieces, the most obvious one is BTS.

Second confession: I strongly dislike pop music, and I clearly have a fraught relationship with my Korean roots, but those seven boys of BTS have changed the way my nieces will grow up more than any classroom lesson, children’s book, or Barbie doll with vaguely Asian features.

It started around 2008, when Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube greatly aided the cultural phenomenon of Hallyu, or the Korean wave. Today it seems like Korea’s eminence is everywhere, from Korean skincare products hailed as holy grails within the beauty industry to Korean dramas populating on Netflix.

In 2020, Awkwafina, a half-Korean, half-Chinese actress, became the first Asian-American to win the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture–Musical or Comedy. Boon Joon-ho’s Parasitewas lauded as one of the greatest films of recent years, becoming the first Korean film to win the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture in a Foreign Language.

This year, Chloé Zhao was the first woman of color and first Asian woman to win the Oscar for Best Director. In a time when hate crimes against Asian Americans are breaking different, deplorable records (and doubling in March 2021 alone),

And then there’s BTS, a juggernaut of the K-pop industry that’s continually made history with its unprecedented success among western audiences. Aside from topping charts and breaking records, like the longest-charting album on Billboard’s World Album chart, the seven-member boy band even holds 20 Guinness World Records, including gaining one million TikTok followers within the shortest amount of time (three hours and 31 minutes), for having the YouTube video to receive the most views within 24 hours (with “Butter” breaking their previous world record with 108.2 million views), and they were the first K-pop act to have the No. 1 album on U.S. charts.

But as I’m distinctly not a fan of pop music, I kept wondering: Why?

They’re young, attractive people who execute highly-choreographed dance moves while wearing carefully styled, trendy clothing – but that’s what every K-pop act is trained to become, thanks to dictatorial record companies who control every aspect of their image and sound (not to mention working them tirelessly, and inhumanely, at times). I gladly wrote them off as the latest empty eye candy popped out by the algorithmic pop factory, which I hate for its inauthenticity and sheer soulless capitalism.

But then, whenever I’ve asked, all the reasons people have for loving BTS sound reasonable: They actually write their own music (which is a sad rarity in K-pop, and too much popular music, in general); they’re very appreciative of their fans; they use their global platform to advocate for self-love and acceptance, including sharing their own experiences with anti-Asian hate and condemning all hate crimes, and even speaking before the U.N. to advocate for youths to accept themselves more freely. Their lyrics are, apparently, thoughtful commentaries on social issues, like materialism and competitive peer pressure.

While Psy’s 2012 global hit “Gangnam Style” satirized materialism and superficiality within the affluent neighborhood of Gangnam (and gave us all a weird horse dance and a song that will be drunkenly played at weddings until we die), Vox speculated, “If it’s possible to ascribe a tipping point to a ‘wave’ [of Hallyu] that seems to be endless, BTS might be it; it certainly seems that the all-boy group has gone as far as a South Korean band can go in terms of making inroads into American culture.”

On a typical day, I’m BTS-fatigued, but the K-pop wave has made it easier to grow up Korean in America…which is more important than ever.

Why have anti-Asian hate crimes broken records this past year? Why has a pandemic made it so easy for Americans to Other Asian faces? How has the Model Minority Myth insidiously inserted itself into how Americans are taught to see Asians, and how has that same myth been crafted and used to divide Black and Asian communities?

Perhaps most importantly, how do you combat centuries of orientalism and the intentional ignorance that most Asians weren’t even allowed to become citizens until after World War II?

Perhaps it starts with a cultural phenomenon. One look at Twitter reminds me that online discourse about #Kpop constitutes over 6 billion tweets on the platform in a given year. Also, other celebrities love them. While appearing at the Golden Globe Awards last year, Bong Joon-ho was asked, “How does it feel…for your country to be leading the way in creativity and vision?” He responded, “I think Korea produces a lot of great artists because we’re very emotionally dynamic people” and cited BTS as particularly influential artists that he appreciates.

I can’t un-know any of these things, for which I’m very grateful. Looking back, in between the all white kids in the commercials for my favorite toys and the all white kids on my favorite TV shows, and the all white kids I grew up beside, I remember SukChin Pak. Anyone who remembers back when MTVNews had integrity (and actually won awards occasionally) will also remember Pak, the Korean-American news correspondent.

Years later, I looked her up and found that she was born in South Korea and her family moved to America when she was five. She’s the only Korean individual (aside from my adoptive brother) I ever remember seeing until I was 18 and ran away to the Big Bad Apple.

Now my nieces have me, and I may be the first Korean female they’ve ever seen, but I am certainly not the only one. At six and two years old, they both know how to use an iPad better than I did when I received my first iPod Touch at sixteen. They Google, they YouTube, and watch TV (the universal babysitter, thanks very much), and the type of media they see today is vastly different than what I had 20 years ago.

And sure, while it’s lightyears ahead in terms of inclusivity, there’s still a demoralizing lack of Asian American representation in American media at large. But the aftershock of Korean-inclusive content after Hallyu, after BTS, is everywhere. In the last 10 years, Korean faces have become a part of America’s cultural landscape. My aversion to K-pop most likely has to do with a lot of internalized baggage and cognitive dissonance that inevitably develops when you were Korean-American back in the wilderness of “What’s Korea?” and conversations beginning with, “So are you Chinese or Japanese?”

It’s cool that the “West” has figured out that Koreans are cool, but among all the new, strange, and complex words I’ll be introducing to my nieces as they grew up, “BTS” isn’t going to be one of them because they’ll already know (hell, they probably already do). And that word’s become a gateway to explain a lot of concepts that can otherwise be mystifying and alienating.

Their classmates aren’t going to ask them what Korea is as if it’s an invalid blank space on a map that’s not attached to any culture, and they won’t spend their formative years figuring out their identities in a giant game of One of These Things Is Not Like the Other. Because they’ll have me, cultural icons who’ve shown the world how cool people like us are, and the otherworldly glowing skin of RM, Suga, J-Hope, Jin, Jimin, Jungkook, and V. (Plus, my oldest niece just discovered BLACKPINK…The revolution has begun…).

This article was originally published in Feb. 2020 and updated in May 2021.

- BTS’ New Album Map of the Soul: Persona is Disappointing – Popdust ›

- The Hollywood Reporter’s BTS Article Is Really Xenophobic – Popdust ›