CULTURE

On Bargain Bin Gems and PlayStation Rentals: Brigandine and Indonesia’s Gaming Culture

21 Apr, 21

Most kids today will never experience the rush of rummaging through a bargain bin at the local video game store and stumbling across a hidden gem.

Now that digital sales outpace physical ones and brick-and-mortar shops struggle to keep afloat, this practice is a lost art.

One vivid memory from around the 6th grade sticks with me. As I waited for my mother to finish shopping at our local Meijer, I searched relentlessly in the gaming section for a cheap PlayStation disc I could coax her into buying for me. I had almost given up hope finding anything worthwhile when my eye caught the back of a CD case.

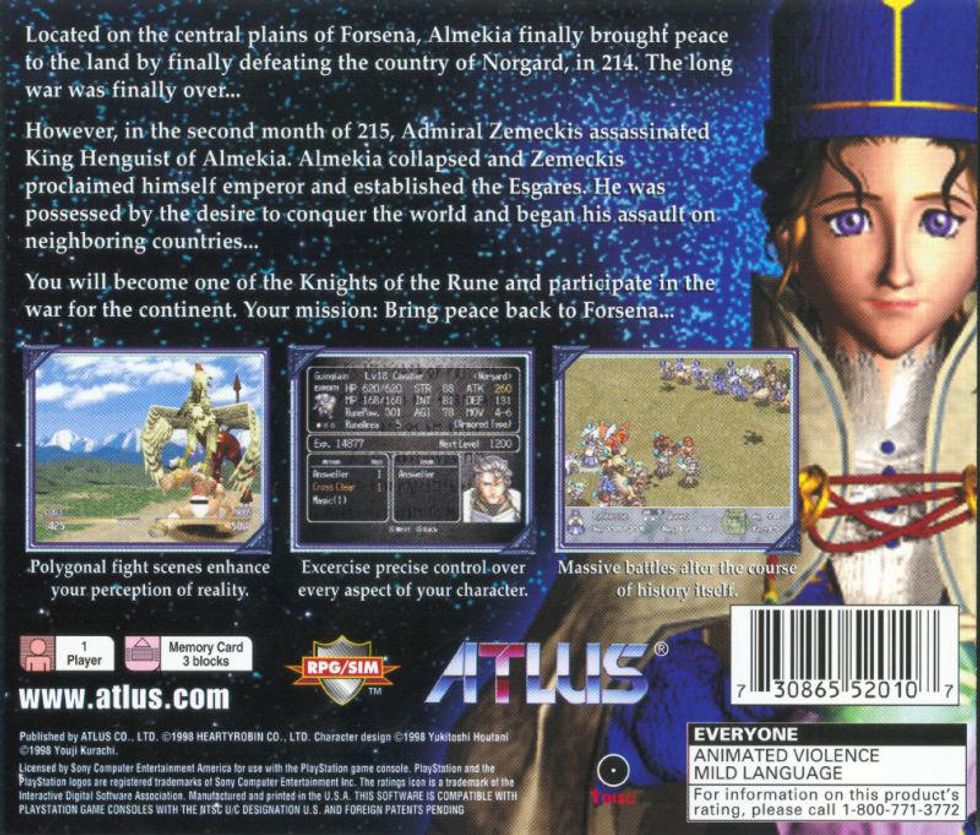

It informed me I had a mission: To bring peace back to the continent of Forsena. A military coup had just ended the reign of Old Almekia, and smaller kingdoms vied for control of the war-torn continent. One screenshot of two armies about to collide held the caption: “Massive battles alter the course of history itself.” Another showed a sprite-model of a “Rune Knight,” all the identifying hallmarks of an RPG dotting his statistics page. The game promised me that I could exercise “precise control over every aspect” of my characters. It seemed impressive enough, so I flipped over the case. Brigandine: Legend of Forsena by Atlus, it read. I hadn’t heard of it, but no matter. For a bargain deal? I was sold. After a bit of pestering, I convinced my mother to buy it for me.

Last year saw the release of Brigandine: Tales of Runersia, the second Brigandine game in the series, which was met with very little fanfare in the United States. Debuting at #6 in Japan and #4 in Taiwan, the game did not have a breakout moment with American audiences – a telling sign in the Covid-19 era gaming boom. Its predecessor, the one I grabbed from the bargain bin, was released over two decades ago, and performed similarly poorly with U.S. audiences. Its 2000 repolish, Brigandine: Grand Edition, which was released in Japan and added multiplayer functionality to the base game, didn’t even make it to North America. As I would later discover, I had just picked up a game that was wildly popular in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, where a unique gaming culture exposed millions of players to a world of games most Americans would never see or hear about.

But back then I was entering the world of Brigandine solo. When I first tried it, I was overwhelmed. I struggled as I maneuvered through the first in-game “month,” which was bifurcated into two phases: an organizing and attacking phase. The former is all grand strategy. The player organizes their castles, interconnected nodes checkered across a map linked by roadways upon which armies can move. During this phase, you also manage your “mana,” which is used to summon creatures to fight for you. The second phase, the attack phase, is where the player must decide who they plan to go to war with that round (or try to avoid hostilities and risk an incursion into their territory).

Battles were new experiences too, combining the first-ever hexagonal (as opposed to square) turn-based tactical battlefields. Your units leveled up, equipped items, and could even evolve in classic-RPG style. Each one of Brigandine’s hexagonal battles felt like a highly complex game of chess. Serious thought had to be given to which units you cared about and felt invested in, and which ones you could afford to lose for good.

I remember losing my first battle in such a painfully decisive fashion – my army of dragons, wyverns, giants, mandrakes, and griffins slaughtered by a clearly superior enemy – that I turned off the game, assuming it must have been in the bargain bin for a reason. It collected dust for a year before I decided to give it another go. Older and wiser, I was able to avoid another crushing defeat the next time I turned it on. After that, I was hooked. Hours of my youth evaporated into the game, creating nearly unstoppable armies and outwitting the admittedly poor AI.

But a big problem remained: no one else seemed to know about Brigandine. And worse yet, it was a single-player game. Aside from a handful of friends I convinced to play, and a couple of primitive notepad Game FAQs, I couldn’t find anyone else who had raised armies of knights and monsters to conquer Forsena. The multiplayer version was never released in the U.S., throwing the possibility of more competitive play out the window. Little did I know that thousands of miles away, the game was amassing a cult following.

Perhaps it should be no surprise that Brigandine gained popularity in Southeast Asia. Fans in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam responded well to the unique combination of grand strategy and tactical and traditional RPG elements, peppered with anime cutscenes throughout. Players, curators, and modders kept the game alive and healthy, even up until today. This is particularly true in Indonesia, where the game has withstood the test of time, sporting a community of players outsizing anywhere else.

Indonesia is a country of 270 million people, with over 10 million concentrated in its capital city Jakarta alone. It’s a place many Americans do not give much thought to, yet its tumultuous history is filled to the brim with world-defining moments. The Bandung Conference of 1955 brought together Afro-Asian countries from around the world, charting an independent path in the era of decolonization. The country’s first post-independence president, Sukarno, once banned American films for being corrosive to Indonesian values. More importantly, however, in 1965 the Indonesians discovered that the head of the American Motion Picture Association of Indonesia was working with the CIA to destabilize the Indonesian government. American films were not reinstated in the country until 1966, after a CIA-backed military coup ousted Sukarno, killing a million Indonesians (Vincent Bevin’s The Jakarta Method is a good place to pursue this digression).

This history reverberates today, and Indonesia faces the familiar problems of countries on the wrong end of global capitalism’s “invisible hand.” Suharto, the military general that overthrew Sukarno in 1965, oversaw anticommunist purges and a turn towards neoliberal economics. This transition lured in foreign capital without the risk of pesky labor unions or political opposition to get in the way. “Indonesia’s economy was effectively redesigned in America,” documentarian John Pilger explains, “giving the West access to vast mineral wealth, markets and cheap labour – what President Nixon called the greatest prize in Asia.” In 1997, the World Bank celebrated Suharto as a “model pupil” of globalization— right before the Indonesian economy crashed, throwing tens of millions of Indonesians into economic misery.

Today, 27 million Indonesians live below the poverty line of $150 a month per family, and millions more fall precariously close. Despite such adversity, the country has managed to become one of Southeast Asia’s fastest growing gaming markets. And like the nation’s underappreciated history, the gaming community is finally garnering the recognition it deserves. Indonesia’s unique political and economic challenges also inspired a unique model of gaming, one that allowed games to develop grassroots popularity at the local level.

While consoles and PCs dominated Indonesian gaming throughout the 1990s and 2000s, players shifted to mobile phone gaming in the past decade, with over 70% of all those who game doing so on their phones. Yet Brigandine has remained alive in the hearts of more than a few Indonesian players.

Facebook’s largest Brigandine fan group, quaintly titled “Brigandine Grand Edition Maniac!!” has over three thousand members. It’s a place where players share screenshots of their armies, discuss their characters and strategies, and disseminate information about the latest mods that increase the game’s difficulty, add new monster units, or upgrade the leveling system.

I had the pleasure of speaking with the page’s administrator, a long-time Brigandine fan from Indonesia, who started the page “on a whim” in 2009. He told me that Legend of Forsena was the most common version of the game there, not the Japanese Grand Edition, but that his page’s title had made more Indonesians aware of the Japanese version. He shared the page’s statistics with me, which themselves tell a story. Of the 3,600 total members, 2,500 (nearly 70%) are Indonesian. 328 are from the Philippines, and another 223 from Vietnam. By way of comparison, the U.S. only has 103 fans of the page. Over 75% of the fans are between the ages 25-34, suggesting they are older gamers who likely discovered the game in the 2000s, not long after its release. The moderator told me that even he was surprised when he made the page: “I found so many Indonesians love this game.”

When I asked him why, what accounted for the disparity between its reception in the U.S. and Indonesia, he had some interesting answers. First, the game was cheap in Indonesia, even cheaper than it had been in the bargain bin I got it out of. Pirated video games would sell for under $1 in the streets of Jakarta, and for similar prices in other parts of Southeast Asia outside of the gaming industry’s primary market base.

Beyond that, he suggested that Brigandine’s popularity could be due to the way that Indonesian kids interacted with games in the early 2000s. Household consoles were not nearly as common in Indonesia as they were in the U.S., and the price of a PlayStation far exceeds the average Indonesian’s monthly earnings. The alternative? Public PlayStation rental shops. Kids could pay a small amount to rent time on a console, enjoying their inexpensive games while onlookers watched. These places functioned similarly to internet cafés, and are known locally as warnet (a portmanteau of warung and internet – Indonesians are known for their portmanteaus, so much so that some writers have lamented the linguistic device in The Jakarta Post).

And like the warnets, Rental PS stores entered a similar trajectory of decline over the past decade. “Some people maybe know Brigandine by watching other people play it at rentals,” the moderator told me, “then got interested and played it too.”

Another Indonesian writer, Syahrul Chelsky, recalls the Rental PS being a formative feature of life in 1990s Indonesia. He would get up early Sunday morning, rushing there to grab the best remote and scramble for a front seat. “As someone who was born in the mid-90s, I am grateful to have spent my childhood in a Rental PS shop (playstation) —although more often as a loyal viewer of rich children who played it,” he said. After all, even if he had the money to play one day, he didn’t always have it the next. In his later teens and early college years, he worked a job at a Rental PS. But after struggling for years, the location finally closed in early March of last year.

This model was far different than North America’s. In the 1990s and 2000s, many American gamers depended on a small selection of videogame magazines to hype up new releases. Indonesian Rental PS shops provided not only a social space for children, but a decentralized network where games less popular in American markets could flourish. Not reliant on flashy advertising in magazines, and with a captive audience of other youngsters waiting for their turn to play, Rental PS shops gave underappreciated gems a chance to stake out a following, far more than household consoles ever could. This model, combined with the game’s low price tag absent a “bargain bin” stigma, made for Brigandine’s winning recipe.

North American audiences are missing out on this classic game. And while they never experienced the release of a multiplayer edition, unofficial English patches for this version abound online. Using remote desktop apps, creative fans have been able to implement a clunky but workable online multiplayer game. Last year Brigandine players even hosted a small “National Brigandine Multiplayer” tournament in the United States, showing that Brigandine can be more than just a forgotten relic of the past. In spite of a lot, or perhaps because of it, Indonesian fans have helped keep Brigandine alive. For that, we owe them a debt of gratitude. It’s time for North American audiences to finally dust off this cult classic, and try their hand at conquering Forsena.