LGBTQIA+

By Alexander Grey (Unsplash)

If you’ve watched BoJack Horseman, read Archie comics, or been rejected by someone who says they like you but your genitals gross them out, then you’re familiar with asexuality — but probably not as familiar as you think.

A 2019 poll found that 76% of those surveyed weren’t able to accurately define asexuality, despite 53% of respondents asserting that they could.

And that’s fine. I can barely do it after years of research, and according to modern definitions I’m a full-fledged “heteroromantic” “asexual.”

According to Dr. Google, that places me among an estimated 1% of the population who are incapable of feeling sexually attracted to anyone, regardless of gender or sex. Or, as Stefani Goerlich explains in sex-therapist-speak, “Whereas heterosexuals are sexually attracted to people of the opposite sex, and homosexuals are attracted to folks of the same sex, asexuals are [sexually] attracted to nobody.”

But, like many, I’m also label-fatigued. I’m torn between feeling validated by the purple, grey, and black banner of asexuality and exhausted by the burden of yet another minoritarian label (I mean I’m also a Korean-American adoptee with a colorful mental health background and an iffy gender identity, but International Asexuality Awareness Day is only one day, so one thing at a time).

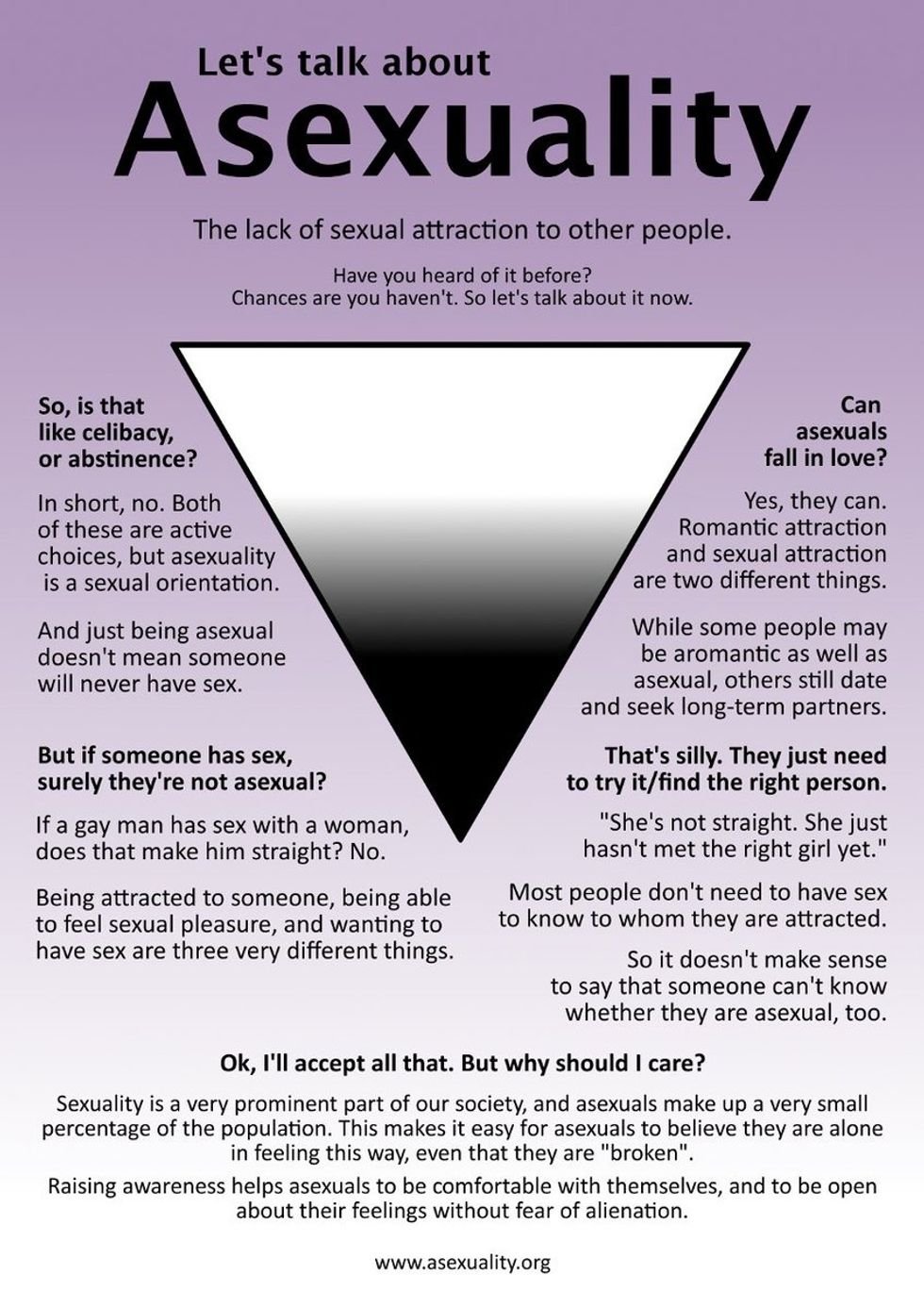

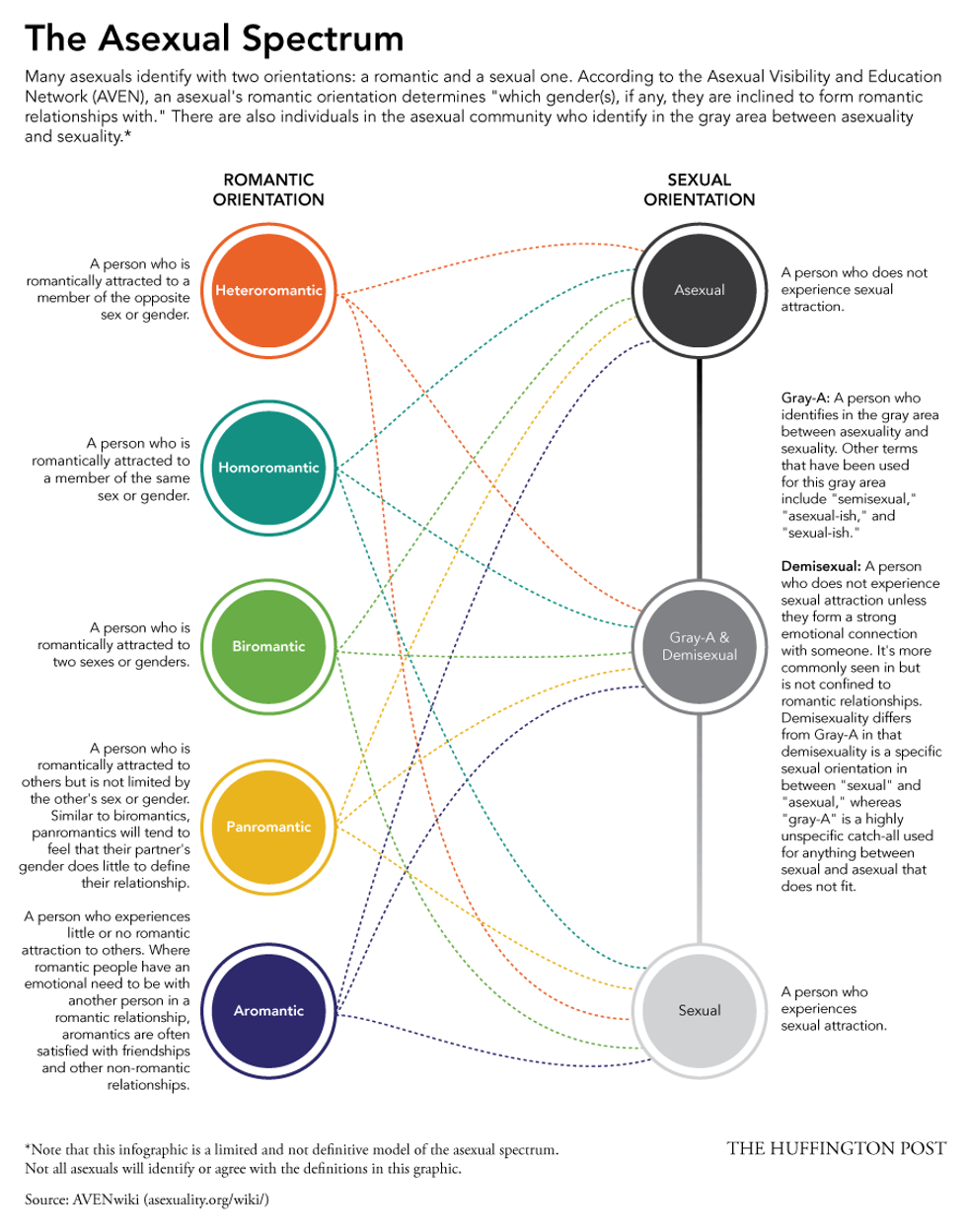

Being “ace” comes with an entire spectrum of its own. The asexual umbrella can still include dating, masturbation, marriage, raising children, queerness, polyamory, platonic primary relationships — and even sex. Sexual behavior is distinct from sexual orientation (as exhibited by any non-heterosexual person who’s had sex with the opposite gender before understanding their sexuality).

Similarly, romantic attraction is different from sexual attraction, and even physical attraction is separate from sexual attraction. Granted, if the CDC is correct that only 1% of the human race is on the asexual spectrum, then 99% of people usually experience physical and sexual attraction simultaneously. As a society, we tend to think of them as interchangeable.

But the asexual battle cry is, “If sex without love exists, why can’t love without sex exist, too?”

It’s a notion so fundamental that it seems novel to speak aloud. Yet, the momentum of the sex positivity movement, today’s hook up dating culture, and more honest representations of raging adolescent hormones in the media all make it easier to conflate romantic interest with sexual attraction — when in fact they’re separate physiological experiences.

As Anthony Bogaert, an asexual researcher and professor at Brock University, toldHuffPost, “[The asexual lifestyle] allows you to see how sex and romance can be decoupled…It allows you to see that when we automatically couple up romance and sex, as if they’re naturally together, that’s not true.”

So let’s not confuse the lack of sexual desire with an aversion to intimacy or even romantic attraction: Being asexual isn’t the same as being aromantic (which Dr. Google defines as “having no interest in or desire for romantic relationships”). Not all asexual people are aromantic, just as not all allosexual (or non- asexual) people are searching for the love of their lives.

Some people, like David Jay, founder of The Asexuality Visibility and Education Network, maintain close, intimate (albeit platonic) friendships as their primary relationships. In Angela Tucker’s 2011 documentary, (A)Sexual, Jay stars as the poster boy for asexuality, organizing AVEN events and giving college lectures and TV interviews to de-stigmatize and spread awareness of asexuality.

Jay’s work is a fundamental reason why Archie comics’bJughead came out as an aromantic asexual in 2015 (though he’s not in CW’s adaptation, Riverdale, because apparently Cole Sprouse is too cute not to have sexy times on TV). And Todd Chavez in Bojack Horseman was given an entire episode and a season four sub-plot to figure himself out as an asexual. It’s 2021 and asexuality has a sliver of media representation: Oh yay, what’s there to criticize!

Here we go: At the end of (A)Sexual, Jay backtracks in a candid, vulnerable interview. His close circle of (allosexual) friends has changed as they’ve deepened their commitments to their (sexual) partners, and Jay ends up admitting that he feels compelled to re-consider his willingness to have sex (even though he feels no desire), saying, “I think sex makes people take relationships more seriously.”

It’s true: Sexless lives are largely treated as if they’re stunted, puerile, or sheltered. Media has either omitted asexuality or used scant representation to problematize it as a character flaw solved by true love or treat it as an oddity for “comic relief.” In the midst of an undeniably sex-obsessed pop culture, being asexual can make you feel invisible, invalid, and non-viable for human connection.

Before establishing AVEN in 2001, Jay said that people like him maybe didn’t even know the right word for what they were feeling: “We know that asexual people have been looking for each other for a long time, but it wasn’t until the Internet that we found each other.” It was only in the 1990s when the term began to slowly circulate as a human orientation (thanks, Oxford English Dictionary), rather than the mode of reproduction for amoebas.

Jay added, “I knew the word ‘asexual’ was really powerful and validating, but [I wanted] to avoid creating a culture of telling people who they needed to be to be part of this community. I started talking about how identity is a tool and not a label—an idea that you should be able pick it up if it’s useful to you and put it down if it’s not, and one that you can redefine for yourself.”

So when it comes to asexuality, what good is another label, another flag, another set of politics?

People may hate how labels put people in boxes; but historically, labels work miracles to validate marginalized experiences, combat alienation, create a sense of community, and provide access to resources. There’s nothing inherently wrong with labels; like Jay says, they’re a tool. They further our work on the complex social project that is a safe, stable, all-inclusive future.

But for now, that world doesn’t exist. And perhaps the most unifying aspect across the entire spectrum of humanity is that everyone (or at least 99% of everyone) wants to get it on with somebody. In English, our very language takes this for granted in the way we talk about sex, sexuality, and attraction. We may not mean to define a person by who they’re attracted to — because, sure, we like to affirm that people are holistic, capable creatures full of light and love and mystery, or whatever — but we express who we’re attracted to by saying, “I am gay/straight/queer/bisexual/pansexual/asexual.” In fact, some activists and even legal experts have taken issue with how we conceptualize orientation as an identity rather than a flexible inclination.

All that’s just to say: When you’re attracted to nobody, you can easily feel like nobody.

In fact, that’s the second rallying cry of the asexual community: Erasure. Todd Chavez said it on Bojack Horseman: “I’m not gay. I mean, I don’t think I am, but I don’t think I’m straight, either. I don’t know what I am. I think I might be nothing.” Sara Ghaleb wrote it for Vox: “As an asexual aromantic—meaning I’m not interested in having sex or relationships—I considered myself ‘nothing’ for years.”

Even David Jay felt that invalidation before he became an activist: “I assumed there was something wrong with me. Something broken.” And, sure, every year around Pride Month publications like HuffPost and Buzzfeed repeat it in hopes to change the narrative of the, statistically speaking, most atypical sexuality out there: “We’re Not Broken.”

But we often feel that way. Claiming the label of “asexual” is inheriting a history of erasure and mockery, disbelief and self-doubt. By far, the four most common responses I’ve received from my potential partners have been (in order of popularity): 1) You won’t know until you’ve tried it! 2) You just haven’t found the right person! 3) Sh*t, were you abused or something? 4) Damn, that’s such a waste.

I’m not broken, and I’m not traumatized. But I am a pretty bad asexual. Because despite my body’s and my mind’s natural instincts that tell me not to push myself to feign an attraction I’m not capable of, despite my ability to fall in love and share intimacy with another person, and despite my past partners who’ve validated that feeling and blamed themselves for not being able to accommodate the forced celibacy I was asking of them — of course I still doubt myself.

While confident and comfortable asexual-identifying people absolutely exist, I’m like David Jay and many other asexuals who can’t help but scrutinize what my body and instincts are telling me: What’s the difference between a body burdened by severe anxiety and a body offline from sexual attraction?

Where’s the overlap between deep social awkwardness and a natural lack of desire? But when I question myself, I do it with hope, because I’d rather change this simple label I’ve equipped myself with than remain ostracized from the people I care about (99% is a very rude number). Not that I’m allowed to say that, because: #Pride.

In (A)Sexual, prominent LGBTQ+ writer Dan Savage mocked asexuality, both as a concept and as a queer identity, saying: “Well it’s funny to think about, you’ve got the gays marching for the right to be c*cksucking homosexuals, and then you have the asexuals marching for the right to not do anything. Which is hilarious.”

He added, “[I]t feels weird to be challenged to embrace a lack of any sexual urge, or impulse, or desire as a kind of sexuality all by itself. And it just looks like such a dodge, from outside…It would be a great escape to say…I’m just asexual, I’m nothing.'” Well, exactly. If asexuality was a choice, I’d choose not to be nothing.