Arts

Interview | Alexandra Silber Cuts Wit with Wisdom in New Memoir, ‘White Hot Grief Parade’

30 Aug, 18

Press Photo

Silber digs into the death of her father in a just-published memoir.

Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods was the very first production I ever worked on during my acting studies at West Virginia University. I can remember it quite vividly. The potato sack-inspired garments stuck to my skin; the costume designer wanted even the crew to be as ingrained in the already-meta production as the cast. A thick heat blanketed the backstage like a tightly-knitted woolen sweater, and even the zigging and zagging of the cast between the trembling shadows and makeshift trees couldn’t assuage the temperature.

It was a dazzling but humble production. If you’ve only ever listened to the soundtrack (the official Broadway cast version or the 2014 blockbuster Hollywood re-up), you’ll know exactly how striking the score, the performances, the unbridled sense of whimsy feels in your gut. Within the nearly 15-minute prologue, the story’s message clubs you over the head. “Into the woods, it’s time to go / It may be all in vain, I know / Into the woods, but even so / I have to take the journey,” Cinderella and the Baker vow, mustering up the courage to venture into the dark, twisty woods. Regardless of what may lie ahead, they dive into the unexpected adventure.

And so is life.

It’s full of devastation, disappointment, and death. Oh, there’s lots of death. And you can never be ready for it.

Accomplished Broadway actress Alexandra Silber (Fiddler on the Roof, Hello Again, Master Class) opens up for the first time on her own brush with death — that of her charming, clever, and passionate father, who succumbed to cancer in 2001— in her emotional new memoir, White Hot Grief Parade. She offers up sly, dry wit as only she can, decorating the sorrow of tragedy in a hopeful, painstaking journey from darkness to enlightenment. In an especially poignant chapter, titled “I Wish / I Know,” an obvious reference to Into the Woods, she situates her misery amongst the gnarled tentacles of the woods.

“Little Red, my eighteen-year-old self, and Cinderella, the self of today. Would that I could look that eighteen-year-old girl straight in the eye, as Cinderella does for Little Red. I wish I could tell her that she is absolutely right — this is the bottom of the well of human pain,” Silber writes, eloquently shading what would soon become ripened wisdom on the aftereffects of heartache, the kind of which no one should ever have to endure.

She continues, “That her innocence is shattered, her childhood at its end. Loss like this will never be ‘OK,’ darling girl, I would say. It will only grow familiar and thus less harrowing. There may never be anything deeper or more painful to wish away, ever again. But now? Now Little Red has earned her passage to the human race. She may now arrive upon humanity’s shores as the inextinguishable woman she is destined to become — that this exact tragedy, in time, if she allows it, will make her soul the richer and escort her to her highest self.”

Pouring her heart out one vignette at a time, Silber’s words carry a message as timely as Sondheim’s, drenched in the “things that make it worth the journeying,” so to speak. “The greatest ‘Into the Woods’ ache is that I will likely never get to play Little Red — which is the character I have always felt the most aligned with,” writes Silber to Popdust in a recent email. “She is the one who faces so much trauma and loss so early in her life. I suppose a part of me will always ‘be’ her.”

“While I would certainly never turn down an opportunity to play Sondheim’s Cinderella, I do feel I have worked through a great deal of her arc through my own life,” she observes, weighing the significance of the fantastical characters to her own tangible reality. “As I also say in [the book], as an actor, I have never seen myself ‘inside’ ‘Into the Woods’ — uncertain which character is ideally right for me to embody and breathe life into. It’s simply a piece I always feel I am seeing from the outside. Perhaps, that means I am the Narrator…”

Having lost my own father four years ago, White Hot Grief Parade reads as much as Silber’s personal recount as words I wish I had the strength to say. And that’s the stinger. Death rips through all of our lives sooner or later, and Silber just happened to have experienced the brutal cycle of life a bit earlier than some of us. “I think that has been the most overwhelming and rewarding part,” she says of readers and others who have personally reached out to her. “Why write a book about grief and your own boring, excessively ordinary life if not to connect to others about theirs; and thus discover that nothing is boring, and no one is ordinary at all.”

Life is an extraordinary thing if you really think about it. It’s a one-take deal, and it certainly is thrilling. “You get what you give in this one glorious life. By leading with authenticity and vulnerability, by exposing your inner-most soft places — and merely exposing, not flooding or forcing your experience down someone’s unwilling throat — we allow others to behold them, at their own capacity and tempo,” says Silber. “Calm exposure invites one to ask the age old human question: ‘You too?’ And that exercise welcomes people to truly connect with one another. “I am so grateful to all who have been courageous enough to share their stories with me. It has been the greatest reward of this entire process.”

Below, Silber spoke with Popdust about collecting up her memories, the book’s dynamic narrative structure, questions she has for God and her estranged family.

Even knowing the background of your memoir, I could never have expected the journey you take the reader on. It’s emotional, raw, earnest, and witty. Did finding and delivering that balance take time to craft?

The experience of chronicling memories, particularly traumatic ones, will always take time to craft, a deliberate energy, and a ton of discipline. But did the tone of the book require fine-tuning? Not really. I chronicled the memories much as I experienced them — at one moment poignant and devastating, the next flat-out hilarious or even preposterous, followed by more honest devastation. That is, of course, much how true life ebbs and flows. We laugh through our tears; we cry in moments of joy. There is no one label that could ever fully capture the essence of an event, a period of time, or even a single moment. I documented the memories as I recalled them — in all their genre-busting detail.

Why did you begin the book with the list of things you’d tell your 17-year-old self?

The beginning of each of the five “sections,” as well as the Epilogue, begin with a return of the adult Alexandra voice, speaking directly to the reader about events from the present day that are in direct relation to the events of my/her father’s death. They are “echoes,” if you will, that resonate in the present, informed by the past. After those introductory section chapters, we continue with the narrative of 2001.

First, I chose to speak to my 17-year-old self, because that was the last time I was truly innocent to the events chronicled in the book — the age of my personal “BC.” Some of the advice is witty and typical stuff we as adults all realize we were idiots about back then (“buy Frizz ease”), and some are very weighty (“go on all the walks with him and tell him all the things”). Second, it was important to me to create a structure that calmed the reader instantly by establishing that the narrator of this book was Alexandra Silber: contemporary adult who “turned out okay” and maybe a little bit more than “fine.” While, in contrast, the protagonist of this tale is an 18-year-old “Al” who has not yet acquired the perspective and wisdom of the narrator. She is just experiencing the events in real-time.

The “things you’d tell my 17-year-old self” was a clear way to establish that there was going to be an ongoing interchange between Al and Alexandra (if you will) throughout this book and creates for the reader a subconscious understanding that our protagonist is not yet fully processed, while our narrator is. Those two “characters” just happen to be the same person — 17 years apart.

Throughout writing this book, did you ever feel you were being torn apart emotionally all over again or was it more of a cathartic release?

I’ll answer in the style of the book:

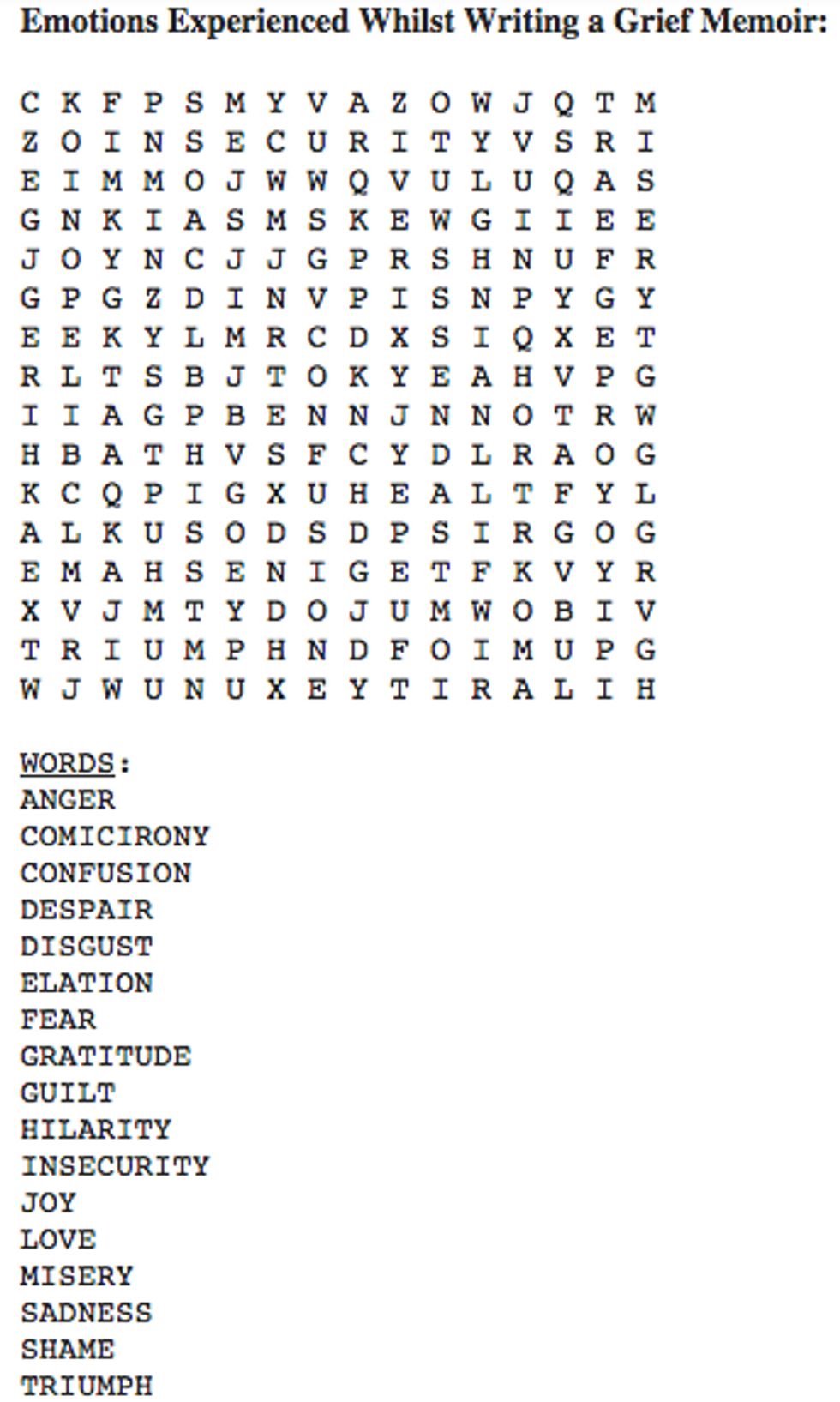

The structure of the book is so layered and complex. Each chapter works as a vignette of a time, place, and emotion. How did you make decisions when to write the chapter out as a stage play or a word puzzle, for instance?

If you examine the book intricately, you come to sneakily discover that not only does the overall narrative storytelling style switch genres chapter-by-chapter, but within the chapters themselves, the writing switches its genres like some sort of bizarre, out-of-control improv game. I suppose that is why I used this format.

To be honest, it wasn’t entirely a conscious creative choice. At first, it was a very necessary personal exercise. The flipping of genres and formats was the result of me attempting to personally express the experience of grief as directly and emotionally accurately as possible, and I found I couldn’t always do that in traditional prose. Some things cannot always be described — they must be intimated as like a photographic snapshot that is worth “a thousand words” (the use of mazes, cryptogram, and haiku). Some things are in fact too painful to look at directly or described in the first person (that was often when I used the scenes). Oddly, the overall effect is very much like grief itself — not just every day, but every minute is a new rush of experience, information and feeling rushing toward you like a freight train. One has no control over it; one must simply endure and surrender to the “parade.”

In addition to grieving and overcoming pain, the book really seems to explore keeping up appearances in a lot of ways. What did this tragedy instill within you about that and how society so often avoids talking about death?

Death is the Great Unknown, and most human beings love nothing more than snuggling up and getting all cozy with certainty. The trouble is — certainty hardly ever truly exists in our lives. The greatest fears all living things hold within them are the loss of someone they love, and the loss of their own lives. Avoiding death and survival instinct are built into the tiniest amoebas, and they don’t even have an intricate death mythology or structure of beliefs about an afterlife. Humanity has been mythologizing death since we had cognizance, one to make peace with it for our own demise, but also to ease the profound suffering of being left behind in death by anyone we love.

Around Christmas, my mom and I were going through some of her life treasures in the basement. “Oh I like those shoes,” I said salivating slightly. “Patience, Al, you can borrow them now but you keep them when I’m dead.” “Roger that, Mom.” “Cheer up. You’ll get it all when I’m dead! Who am I gonna leave it to — the cat?” This level of banter is pretty standard for us.

But the other day I experienced a very special career highlight, and my wonderful, witty mother was there to bear witness. We have an unspoken tradition where after every major life event of mine (such as an opening night, a book launch, a concert), she takes me aside, and we pause a few minutes to revel in what has just transpired. After we did that, I paused and said: “Mom. Just so you know, this tradition means everything to me.” “Me too,” she replied. “And,” I continued after reflecting a moment, “I don’t know about the details of the afterlife and all that, but I’m just letting you know now, that if you do get to come back and haunt or visit or say hi, this ‘after the show’ moment would be when I’d really like to know you’re popping in.” “Okay,” she said, then smirking added “Good talk.”

We laughed. Life and death and real-talk chat is no big deal to the Silber ladies anymore. As you can see, the ability to so blithely operate in that kind of dialogue does not put a damper on the joyous occasion. It made it even more memorable, without being a huge downer. Taking death and grief out and looking at them directly seems unpleasant, unnecessary, and downright “grim,” but it removes the stigma from a human experience every single one of us is going to have sooner or later, and avoiding the subject is not going to prevent it, and certainly not the solution for making any kind of peace with it.

My suggestion is to very simply: think and talk about it. Recognize that you might be avoiding the subject out of discomfort or fear. The more you accept the reality of death and grief, the more you can get on with the business of truly investing in and fully living your life.

Why did you make the choice to fictionalize Rabbi Syme?

What a wonderful question. Ah, beautiful beautiful Rabbi Daniel Syme. I went about fictionalizing the real Rabbi Syme (who is chronicled literally in WHGP) into the fictional version that captured his spirit, in the Rabbi Syme. The real Rabbi Daniel Syme was a crucial advocate to and for not only me, but to and for my father’s human legacy.

Fictional Rabbi Syme (in ‘After Anatevka’) is based very loosely upon the real-life Rabbi Syme — loosely because my description in the novel is not so much a literal, but more of an evocative, recollection and honoring of his influence. Real-life Rabbi Syme and I only spent a collection of minutes together in 2001, but they were crucial minutes. He gave me the gift of delivering the eulogy at my father’s funeral service, as well as bearing witness to it when he led the funeral service, and above all, he gave me an hour of his time months later, reminding me of what was eternal, and chartering a map toward the beauty, strength, and individuality of my faith. Irreplaceable gifts one can never forget. The fictional version of the character was my way of honoring the man who was my father’s advocate, and thus, Perchik’s (who is modeled in many ways after my father). He was also my first spiritual teacher of any kind.

The influence of Rabbi Syme proves another true-to-life maxim: that we never know the depth of the influence we have upon one another. A fleeting moment to one, might bear a lifetime of profundity to another, for better and for worse. So, it is in these tiny actions that we must recognize that our influence on Earth is vast, has meaning, and should never be taken for granted.

[Silber has also shared further thoughts in posts on her blog, which you can read here]

In the chapter called “Grandparental Gunfight,” you receive a letter from the Silber Family, who vow to cut you and your mother out of their lives. Do you remain estranged from them? Has any of your father’s family reached out about this memoir?

My grandparents have passed away, and I genuinely hope they are resting in peace despite their trash can behavior. My father’s siblings, cousins, and all their children? They know where how to find me if they want to. They clearly do not, and that is absolutely okay.

I have heard from my brother (more on that in a moment) that my aunt comes to see me sometimes in Broadway plays but doesn’t tell me about it. She buys a ticket, attends, and leaves without a word. There is something quite touching in that and yet also extremely odd. I feel especially sad about my aunt because as liberal, artistic Jewish women, I always thought we’d have so much in common. I’d entertain that dialogue as long as we never had to comb over the minutia of the past. Life is too short, and I have personally found my peace.

In the acknowledgments, I state that I decline to chronicle my half-brother Jordan’s arc of this story, his relationships with both our father and his family. Jordan, his beautiful family and I enjoy a very close relationship that grows closer every day. I felt strongly that first, his story was not mine to tell, and second, in reality, we were so separated at the time that the book takes place that declining to mention him was somewhat accurate to my experience of the events. I adore them all and feel that our close relationship is the ultimate triumph of our family’s dysfunctional history.

With the chapter “Where Memories,” you state that you “have always clutched fiercely onto ordinary moments.” As I was reading the book, I had a pad of sticky notes and immediately scrawled “Anton Chekhov,” whose plays featured plots with very little actually happening (The Cherry Orchard is a favorite). Many people don’t or aren’t willing to find the poeticism in the mundane, the little moments that don’t seem to mean anything on the surface. Is it human nature to only remember the big, life-changing moments?

It is interesting you mention Anton Chekov and ‘The Cherry Orchard.’ I don’t state it directly, but the “mysterious man” Perchik meets in the Moscow bar in 1903 (about two-thirds of the way through ‘After Anatevka’) is indeed Anton Chekhov. I drop about a dozen or so clues, even going so far as to have Perchik inspire Chekhov with the phrase “All Russia is our orchard…” but I never state it explicitly. It was my little nod to the theatre.

I don’t think it is human nature to only focus on big life moments — I think many people vividly recall the seemingly minute details of their lives. What I think most people do not practice is the meaning-making around any of these details. Making meaning of our lives is why many people participate in religion, why they read and go to the theatre, why they read horoscopes, and attend spiritual gatherings. Not every human being finds meaning-making fruitful — some prefer to live utterly in the present, and that is okay if it works for them.

I happen to be a person who not only enjoys but needs to make meaning of my and all human life. I do think I have a gift for creating a myth around an experience almost instantaneously, but as a few very wise friends have observed, sometimes my speedy ability to mythologize hijacks my experience of the moment itself. And noting that, I endeavor to stay fully aware in the present and make meaning later.

How would you urge the reader to learn to approach life as you do, in relishing the mundane and the ordinary?

By recognizing that absolutely nothing is mundane or ordinary.

But also: Pause. Breathe. Look in people’s eyes. Ask thoughtful questions and really listen to the answers. Practice gratitude.

What questions do you still have for God?

Why so many Fast and the Furious movies, Big Guy?

and

BE HONEST ARE YOU JUDGE JUDY?

Concerning everyone who helped you through this tragedy, are you still in contact with them?

All of them. ‘Grey’ is a hugely successful theatrical designer. ‘Kent’ is changing the world working for a State Senator and just had a baby. Lilly is still my best friend and plays oboe all over the world. I saw her last month at the Metropolitan Opera playing Strauss at American Ballet Theater. They are, all, triumphs of human beings.

Follow Alexandra Silber on Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

Jason Scott is a freelance entertainment journalist with bylines in B-Sides & Badlands, Billboard, PopCrush, Ladygunn, Greatist, AXS, Uproxx, Paste and many others. Follow him on Twitter.

POP⚡DUST | Read More…

READY TO POP | Harrison Wheeler, Haley Vassar & More Pour Out Shots of Sugar

Popdust Presents | Shane Hendrix is Ready for His Close-Up

Interview | Emily Kinney Chronicles On-Again, Off-Again Romance on New Album, ‘Oh, Jonathan’

- Alexandra Silber Theatre Credits ›

- Actress Alexandra Silber reflects on loss and solace in ‘White Hot … ›

- Alexandra Silber | Playbill ›

- Alexandra Silber (@alsilbs) • Instagram photos and videos ›

- Alexandra Silber – IMDb ›

- Alexandra Silber (@alsilbs) | Twitter ›

- Alexandra Silber – Wikipedia ›

- Alexandra Silber ›