Jordan Peterson

Photo by Tony Norkus (Shutterstock)

Take Sisyphus as an icon of masculine identity: see the stalwart, self-sacrificing, Adonic man on his hill, the hulking burden of his rock, and his never-ending tread.

How does he go on? Albert Camus once assessed, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” But why?

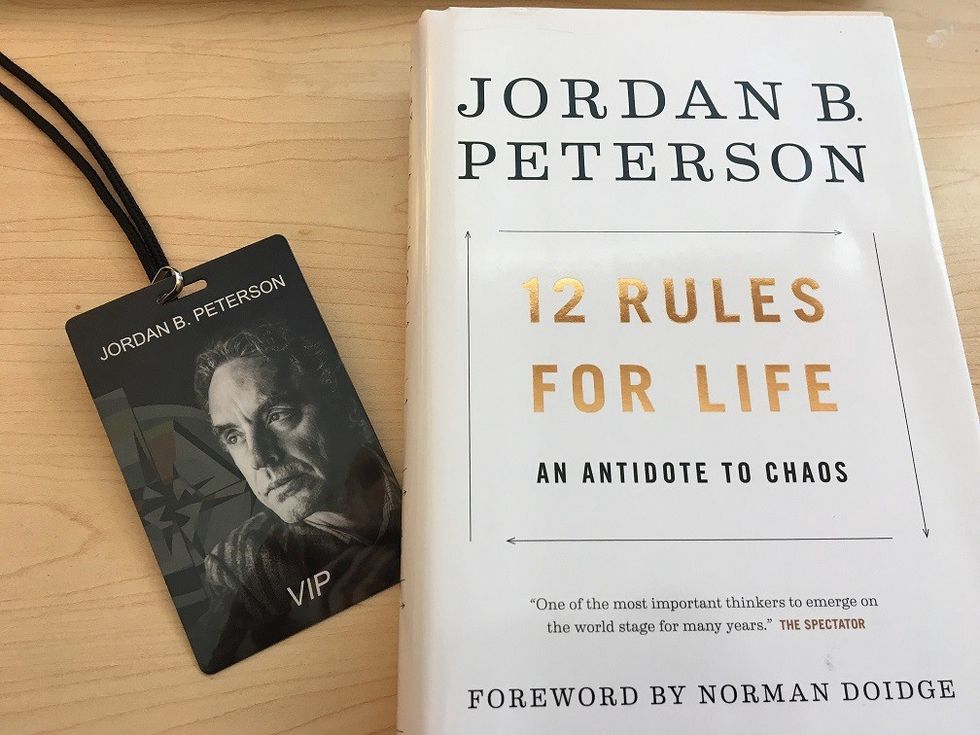

Jordan Peterson is a clinical psychologist who has reportedly sold over a million copies of his 2018 self-help book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. In little more than a year, Peterson went from teaching at the University of Toronto, where he’d publish his lectures online to a meager audience, to edifying 1.5 million (mostly male) YouTube subscribers about their own Sisyphean struggles.

He is one of the most notable members of the “intellectual dark web (I.D.W.),” an online cohort of talking heads who moralize under the guise of critiquing society and self-aggrandize by generating backlash for their ultra-conservative views. They publish videos, lectures, and essays as standalone iconoclasts, untarnished by political correctness, leftist agendas, the dogma of logic, or common sense. The I.D.W. sprouted from frustration over outrage culture and domineering progressivism they found on college campuses. As an alternative, this guild of pseudo-philosophers offers themselves as mythical founders of their own tribe of unorthodox thinkers. They stand firm against “radical left-wing identity politics” that spread the “liberal fallacy” that meaning can be found in a multiplicity of perspectives rather than one doctrine of truth.

In particular, Peterson’s school of thought features the dangers of identity politics, the natural order of patriarchy, and the claim that postmodernism is nothing more than “neo-Marxism” in disguise, which, on its own, means… nothing. That said, it’s safe to assume he means “cultural marxism“—the pseudo-academic term used by the alt-right to slander any and all social progress that subverts the supremacy of male, white, western culture.

Peterson’s quick rise to internet fame was launched by a video series railing against “social justice warrior, left-wing radical political activists” dominating campus culture and threatening freedom of speech. The crux of the three-part lecture was protesting Canada’s C-16 bill, which forbade discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression by prescribing the use of transgender persons’ preferred pronouns. He claimed that the bill (which passed) set a “dangerous” precedent of transforming some citizens’ opinions (like his own) into “hate speech.” He protested, “I’m not using the words that other people require me to use. Especially if they’re made up by radical left-wing ideologues.”

Critics frame him as “the stupid man’s smart person,” as he whitewashes ultra-conservative beliefs with academic-sounding bluster. On feminism, he says, “The idea that women were oppressed throughout history is an appalling theory.” On Islamophobia, he says that’s “a word created by fascists and used by cowards to manipulate morons.” The very idea of white privilege is, according to the professor-turned-YouTube-philosopher, “a Marxist lie.”

Still, Peterson has also been called “the custodian of the patriarchy” who speaks “the gospel of masculinity.” His uniquely empty pedagogy satisfies the needs of a bevy of young men who feel undercut by feminism and adrift among postmodernity’s mixed messages of cynicism and empowerment, irony and empathy, self-referentiality and self-contextualization as a nostalgic generation lost in time. Like all the soapbox sophists of the I.D.W., Peterson frames disaffected young men as mythic-grade heroes who have been undermined by modern liberalism and its loose moral structure.

Set up to fail by society, how do these Sisyphean men persist? As Peterson lectures, “The purpose of life is finding the largest burden that you can bear and bearing it.”

The King of Corinth: Man Is King

“If you can’t understand why someone is doing something,” Peterson advises in his book, “Look at the consequences of their actions, whatever they might be, and then infer the motivations from their consequences.” Actually, it’s Sisyphus’ utter lack of consequences that reveals a paradox in his motivations—as he climbs an endless summit, his constant failure only concedes to renewed hope for success. But to professional sophists like Peterson, this type of failure is actually a testament of strength and persistence against trying odds. Sisyphus is the happy fool who defines himself by the plight he manufactures; he is the creature who suffers because he valorizes his own suffering. As such, the myth of Sisyphus conjures the accompanying image of an Ouroboros, the snake consuming its own tail as it devours and then remakes itself.

Or, a more appropriate 21st-century term might be a “failson,” a moniker coined in 2016 by the hosts of the testosterone-fueled, nominally socialist podcast Chapo Trap House that perfectly encapsulates Peterson’s fanbase. Young, white, middle-class men, lost in the ennui of material comfort, find themselves devoid of purpose or identifiers in an age when difference is currency. Yet, buoyed by family resources (and often a dose of white privilege), they’re unable to reach rock bottom where they’d be primed to rise in an All-American underdog narrative. By subsisting on their privilege, they destroy their own ability to prove themselves in a cycle of self-sabotage.

One of Chapo‘s three hosts, Will Menaker, colors the image of the failson as the young adult male who “goes downstairs at Thanksgiving, briefly mumbles, ‘Hi,’ everyone asks him how community college is going, he mumbles something about a 2.0 average, goes back upstairs with a loaf of bread and some peanut butter, and gets back to gaming and masturbating.” Fellow host Matt Christman describes failsons as “useless people who do not fit into the market as consumers or producers or as laborers. Some of them turn into Nazis. Others become aware of the consequences of capitalism.” And a substantial number turn to Jordan Peterson.

Because in Peterson’s philosophy, the failson is far from a failure; rather, he is a competent man who has been failed by some greater system at work: the rock and hill are conspiring to keep the man down. For millions of young men, adapting Peterson’s worldview applies the ideological balm that society has failed to teach them about personal responsibility, instilled them with self-consciousness about their “so-called toxic masculinity,” and then dared to punish them for their shortcomings.

Poor Sisyphus—especially if we recall that the legacy of Sisyphus actually begins with his cunning as King of Corinth, where he reigned with the monarchical conviction of a god, ruling his kingdom by holding himself as the highest principle—

—as all self-possessed men must do, in Peterson’s view. In an age when “the masculine spirit is under assault,” as Peterson opined to The New York Times, self-principle is the only antidote to the liberal disease that disenfranchises young white men. In this belief, Peterson is joined by other conservative dilettantes of the I.D.W. like Ben Shapiro, Sam Harris, and Eric Weinstein. Through allegiance to their own logical fallacies, they stake claims for themselves in the Internet niche of predominantly male millennials searching for meaning without an authoritarian figure to turn to. They arm failsons with their boulders— the belief that the “masculine spirit” is their divine right— and they rally them uphill against the forces of leftist politics and liberal ideology. They replace meaninglessness with myth, framing today’s young men as leaders against a “backlash against masculinity.”

Youth is an integral factor among Peterson’s conservative followers, who don’t fit into the middle-aged Republican Establishment and who feel alienated—not to mention attacked—by young, radical liberals. While Peterson’s worldview diverges from his cohort’s at occasional crossroads, the figures of the I.D.W. have more in common than mere self-inflation, solipsism, and generous confirmation bias. They each gain followers by diagnosing a postmodern disease in young men suffering from unmet potential. And their offered cures denounce progressive ideology, replacing it with their own and disguising turgid opinions as objective social theories.

As a result, Peterson’s body of work is an odd hybrid of polemical rhetoric and self-help platitudes. One of his oft-noted “rules” is simply to “stand up straight” and present oneself bravely to a world adversarial to men. Imagine Sisyphus being bolstered by that advice, pushing his burden proudly as a trophy rather than a shame.

Now imagine Sisyphus giving sold-out lectures about the righteousness of his rock, philosophizing about his cleverness, and publicizing his martyrdom. He’d stand up straight and claim he’d conquered his hill, when all he’d done was dig himself a cave.

Body Unburied: Man is Self-Determined

Like all influential men, Peterson has his detractors. Predictably, the professor finds himself the target of activists who denounce his views as sexist, racist, transphobic, and generally execrable thoughts. Undeterred, he’s dismissed his critics as “rabid harpies.” Peterson finds his protesters to be, at best, leftists who are offensive in their oversensitivity, and, at worst, hypocritical oppressors who actually victimize his followers with their liberal agendas.

In fact, he urges that his followers have a “moral obligation” to respond to ideas that threaten their worldview. One of his bombastic “12 rules for life” is to acknowledge feelings of resentment, which he calls a “revelatory emotion.” He says that resentment can signal “there is tyranny afoot—in which case the person subjugated has a moral obligation to speak up. Why? Because the consequence of remaining silent is worse. Of course, it’s easier in the moment to stay silent and avoid conflict. But in the long term, that’s deadly. When you have something to say, silence is a lie—and tyranny feeds on lies.”

What Sisyphus resented most was his own mortality. When Death came to his castle to collect him, he refused. He manipulated Death and enchained him, infuriating the gods with his self-satisfaction.

Relentless, Peterson brandishes his controversial opinions in interviews and public confrontations with protesters as well as his posted media. Armed with pedantry, he seems to argue for a hegemony of thought—his own—by humoring his detractors both in print and in person. He touts in his book, “Intolerance of others’ views (no matter how ignorant or incoherent they may be) is not simply wrong; in a world where there is no right or wrong, it is worse: it is a sign you are embarrassingly unsophisticated or, possibly, dangerous.”

Absurdly, Peterson often rails against this “dangerous” intolerance. After all, freedom of speech was the basis of his stance against the C-16 bill (despite his “embarrassingly unsophisticated” reading of that law). He regularly emphasizes the danger of “social justice warriors” who challenge his thoughtfully cherry-picked evidence. He’s warned that they’ll do anything to “enforce their view of the world.”

Still, despite being embraced by conservatives and the alt-right, Peterson insists, “I don’t really regard myself as a political figure.” Because above all, Peterson is a professor—the worst kind, in fact, a self-proclaimed “professor against political correctness.” Which is to say that Peterson is a professor of negation, not substance. Peterson is not politically correct because his biases limit his competence. He is not a postmodernist because he lacks a theoretical foundation. He is not a feminist because his insular perspective is out of touch with social reality.

In Hades: Man is a Fool

The life of Sisyphus ends where the myth begins. Before succumbing to death, Sisyphus decreed that his wife Merope was to leave his body unburied. He knew his cunning would allow him to return from the underworld and resume his reign—and in fact, he did, until he died of old age, a satisfied king. Even though Sisyphus was exiled to his hill as punishment, he persists in his sense of self-satisfaction. While Sisyphus may find happiness in simply being a fool, being happy is not his motivation.

Of this, even Peterson would approve. He counsels in his book, “‘Happiness’ is a pointless goal. Don’t compare yourself with other people, compare yourself with who you were yesterday. No one gets away with anything, ever, so take responsibility for your own life.”

To young men who feel unmoored and overwhelmed by the freedom of self-determination, there’s an online niche where meaning is concrete and authorial big brother-philosophers are waiting to assert capital-T Universal Truths.

Coddled by these philosophies, young conservatives can see their own struggles in Sisyphus’ failure, grappling with his rock in the same way they’re doomed to buckle under the oppressive gravities of liberalism, feminism, and pressures to succeed. If not that, then the hero’s perennial penance is that he stands apart on his hill, isolated within a superior reality of his own making.

As Peterson writes, “You conjure your own world, not only metaphorically but also literally and neurologically. These lessons are what the great stories and myths have been telling us since civilisation began.” Figures like Peterson exemplify the modern man who falls for his own myth, believing himself cursed when society sees him as fallible, not an indomitable character. Even as he’s dismissed by most serious academics, Peterson presses on, even fitting himself into the model of Sisyphus as a masculine icon; his recent surge in mainstream popularity feels near the top of the hill, the point just before the boulder tumbles back down.

POP⚡DUST | Read More…

Popdust’s Best of 2018: Best of the Best

American Art Will Flood the Internet on New Year’s Day

“Macaulay Culkin” is Macaulay Culkin’s New Middle Name

- Jordan Peterson (Still) Wants to Give You Life Advice – Popdust ›

- Jordan Peterson Shocked to Learn He’s Always Been Red Skull – Popdust ›

- Joe Rogan Is Right — Straight White Men Are Being Silenced! – Popdust ›

- A Field Guide to Jordan Peterson’s Political Arguments ›

- Why Can’t People Hear What Jordan Peterson Is Actually Saying … ›

- Jordan Peterson’s Bullshit ›

- Jordan Peterson, explained – Vox ›

- Jordan Peterson’s Flimsy Philosophy of Life | Psychology Today ›

- How dangerous is Jordan B Peterson, the rightwing professor who … ›

- What’s So Dangerous About Jordan Peterson? – The Chronicle of … ›