Between constantly refreshing election maps and giving too much mental space to Nevada and Pennsylvania, the circus of the past few days has made at least one thing unerringly clear: The United States is still a fundamentally racist country.

This, we knew. But after June’s promises of radical change and widespread racial reckoning in the face of President Donald Trump’s blatant bigotry, I have to admit I had a glimmer of hope for a landslide Joe Biden victory hope was quickly dashed.

Though I’m disappointed by the revealing closeness of this election, at least it offers no more scapegoating, no more hiding from the prevailing reality of American bigotry. This time, as compared to 2016, Trump voters knew what they were getting (blatant white supremacy), and they checked “Donald J. Trump” on the ballot box despite.

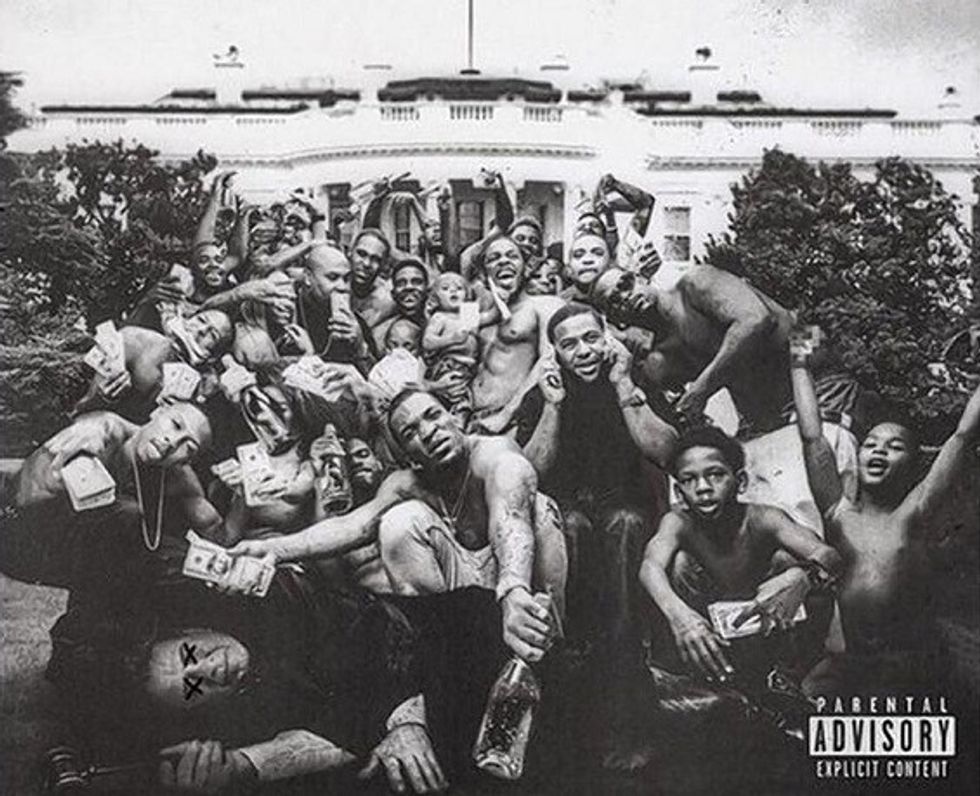

Yet, I still have hope. Mostly because I’ve been listening to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly on repeat all week. Kendrick’s three most notable albums are all distinct. 2012’s good kid, m.A.A.d city is a masterpiece of storytelling about growing up in Compton that revitalized the concept album. The most recent, 2017’s DAMN., is Kendrick’s ƒPulitzer Prize winning and most commercially successful work. But To Pimp a Butterfly remains his most culturally significant work, arriving as the anthem to the summer of racial protest in 2015.

It’s hard to think of a contemporary rapper with more (positive) political influence than Kendrick Lamar. To Pimp a Butterfly is unrestrained. The political commentary in good kid, m.A.A.d city was artful and anecdotal, but TPAP is brazen while retaining lyrical nuance.

What makes Kendrick’s music so compelling–and effective enough to jolt me out of election induced despair–is that it does what rap was created to do: protest.

The marginal results of the 2020 election might just be the revelation needed to spark revolution, but only if we push for it. And while it’s been hard enough to get out of bed this week, when the revolution comes, these are the Kendrick lyrics reminding us that the revolution continues…

“What you want? A house or a car? Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar? / Anything, see, my name is Uncle Sam, on your dollar / Motherf**ker you can live at the mall” — “Wesley’s Theory” (feat. George Clinton & Thundercat)

In “Wesley’s Theory,” the opening track of the album, Kendrick is searingly self-aware. The song role plays the expectation of excessive spending and posturing by Black celebrities, both from the perspective of himself and Uncle Sam. This line comes from the Uncle Sam character and is repeated later in the album in “Alright” and “Lucy.”

Here, the promises of status symbols are equated to the promises of reparations made to unenslaved Back people after the Civil War — which we know to have been false. With many claiming to have voted for Trump this election for economic reasons, including an increase of Black men, Kendrick opens with a statement on the commodification of Blackness and the false security of Black Capitalism.

This criticism opens the album to the clear fact that despite Kendrick’s commercial success, he knows that money won’t save us. Money is part of the problem.

“Thought money would change you, made you more complacent, / I f**kin’ hate you, I hope you embrace it” — “u“

This line from “u” feels unbelievably prescient in the wake of rappers like Ice Cube and Lil Wayne endorsing Donald Trump for President. Again, Kendrick is critical of the profit motive but not surprised or mourning his losses. He’s unapologetic and leaves no room for anything less in return.

Sorry! No “cross the aisle” friendships for K-dot or us!

“Ain’t nothin’ new, but a flu of new Demo-Crips and Re-Blood-licans / Red state versus a blue state, which one you governin’? / They give us guns and drugs, call us thugs / Make it they promise to f**k with you / No condom, they f**k with you / Obama say, “What it do?” — “Hood Politics“

Kendrick pulls no punches in “Hood Politics.” Despite frequent invitations to the White House under the Obama administration and photographs with the then-president himself, Kendrick does not hesitate to name Obama as complicit in an oppressive system of power.

In this line, he equates the prominent political parties to gangs, both with explicit agendas to kill and incriminate Black people. Kendrick underscores the lack of direct action by President Obama, despite his Blackness. Though with so much riding on the 2020 election, the established powers that be can only do so much — will only do so much.

“I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it / Institutionalized, I keep runnin’ back for a visit” — “Institutionalized” (feat. Bilal, Anna Wise & Snoop Dogg)

What Kendrick conveys through all his music is the interconnectedness of the micro and the macro, the personal and the political. His anecdotes, skits, and observations are all vehicles through which to see the larger societal structures of oppression.

In “Institutionalized” he says it plainly: Oppression works in cycles. The revolution will necessitate breaking these cycles, but not through upward mobility — Kendrick says here he’s still trapped in the ghetto despite his success — but by community care and breaking the system which creates these cycles.

“How can I tell you I’m making a killin’? / You made me a killer, emancipation of a real n****” — “The Blacker The Berry“

Violence is an inescapable fact of the cycles created by the system. Kendrick’s music often contains gunshot sounds and is partly defined by its focus on gang-related violence. While Kendrick doesn’t shy away from implicating himself in this violence, he attributes its greater roots to systemic oppression — the biggest bad, the greatest violence.

And again, it all comes back to the dollar. To make a killing depends on the killing and incrimination of Black people. This rhetoric rings especially loud and clear in the wake of a summer of protests, which were framed as riots defined by looting.

Violence by the oppressed is a symptom of that oppression, and the harm caused by the oppressed can never equal the harm done by the oppressor.

“Even if master’s listenin’, I got the world’s attention / So I’mma say somethin’ that’s vital and critical for survival / Of mankind, if he lyin’, color should never rival / Beauty is what you make it” — “Complexion” (feat. Rapsody)

The turn Kendrick makes by the end of this album is back towards the self–but not in the self-serving way of “Wesley’s Theory.” “Complexion” is an ode to Blackness, and a manifesto on loving ourselves. Part of the violence of institutionalized oppression is the socialization of self-hate.

Kendrick announces in this line that this song is addressed to Black people and that the pursuit of self-love is critical to survival. Self-care is community care, essentially.

“Complexion” addresses colorism, desirability politics, and generational trauma, but it all comes back to this: Blackness is multidimensional. Drawing on his criticisms of commodification in the first track, this time success does not mean status symbols. This time the goal is healing for our own sake.

“Everybody lack confidence, How many times my potential was anonymous? / How many times the city making me promises? / So I promise this – I love myself” — “i“

The first single from the album, “i,” is a celebration of Blackness. To love oneself in this song isn’t a small thing. It comes after realizing that, despite the odds and the systematic barriers, we have potential and we have ourselves. Kendrick doesn’t count on the city or the structure; he counts on the community; he counts on himself.

“We gon’ be alright” — “Alright“

Upon its release, “Alright” was called the epitome of a protest song and the unofficial anthem of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s a mantra.

It’s what I whisper to myself as I refresh the page again and try to imagine the future: We gon be alright. We are.

- Top 50 Songs of the Decade – Popdust ›

- 2014: Macklemore Over Kendrick Lamar – Popdust ›

- Kendrick Lamar and SZA drop a new banger “All the Stars” – Popdust ›

- Kendrick takes aim at Drake’s style on ‘DAMN.’ – Popdust ›

- 6 Times Kendrick Dissed Fox News (That You May Have Missed … ›

- A deeper look into Kendrick Lamar’s “DAMN.” – Popdust ›

- Kendrick Lamar “Backseat Freestyle” Lyrics Breakdown: Good Kid … ›

- Kendrick Lamar Albums Ranked from Worst to Best – Popdust ›