Myspace

At some point in 2006, I changed my name on Myspace from “Dan” to “D for Dandetta.”

It was my freshman year of high school, and V for Vendetta had just come out in theaters (my friend and I snuck in after buying tickets to see Amanda Bynes’ She’s the Man). As a young, as-of-then-undiagnosed autistic nerd who thoroughly misunderstood social conventions, I decided that since V for Vendetta was easily the coolest R-rated movie I had ever seen, cute girls would think I was very cool by association if I tailored my online social presence to reflect it.

I made my profile background black to represent the darkness in my heart, and I changed the text color to red because revolution is bloody or something. I also set Vincent Valentine’s theme song from Final Fantasy VII, which was edgy and mysterious just like me, to play on my profile in an endless loop.

One girl I had a crush on actually did start calling me “Dandetta.” I thought she used it as an affectionate nickname, but in retrospect, probably not. In my defense, my brain was not fully developed.

Practically every millennial who dwelled on the Internet anytime from 2003 to 2010 holds their fair share of Myspace nostalgia, too.

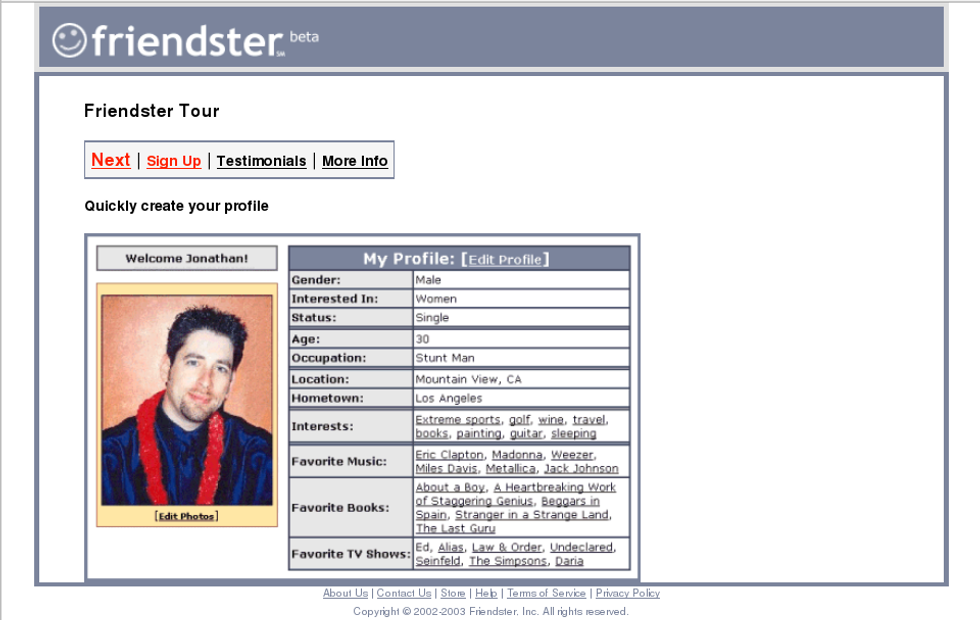

“Social media,” at least as we know it today, didn’t exist prior to the early 2000s. A number of smaller, conceptually similar sites like SixDegrees.com and Makeoutclub.com sprung up in the late ’90s, but none of them ever caught on in a big way, and online social interaction still primarily lived across disparate forums. Then came Friendster in 2002 and Myspace in 2003, one right after the other.

Both sites had similar functions but very different ethos. Friendster was the more mature option, allowing users to create simple, aesthetically uniform profiles—a picture, a list of hobbies, a list of interests, etc.—through which they could easily connect and communicate with others.

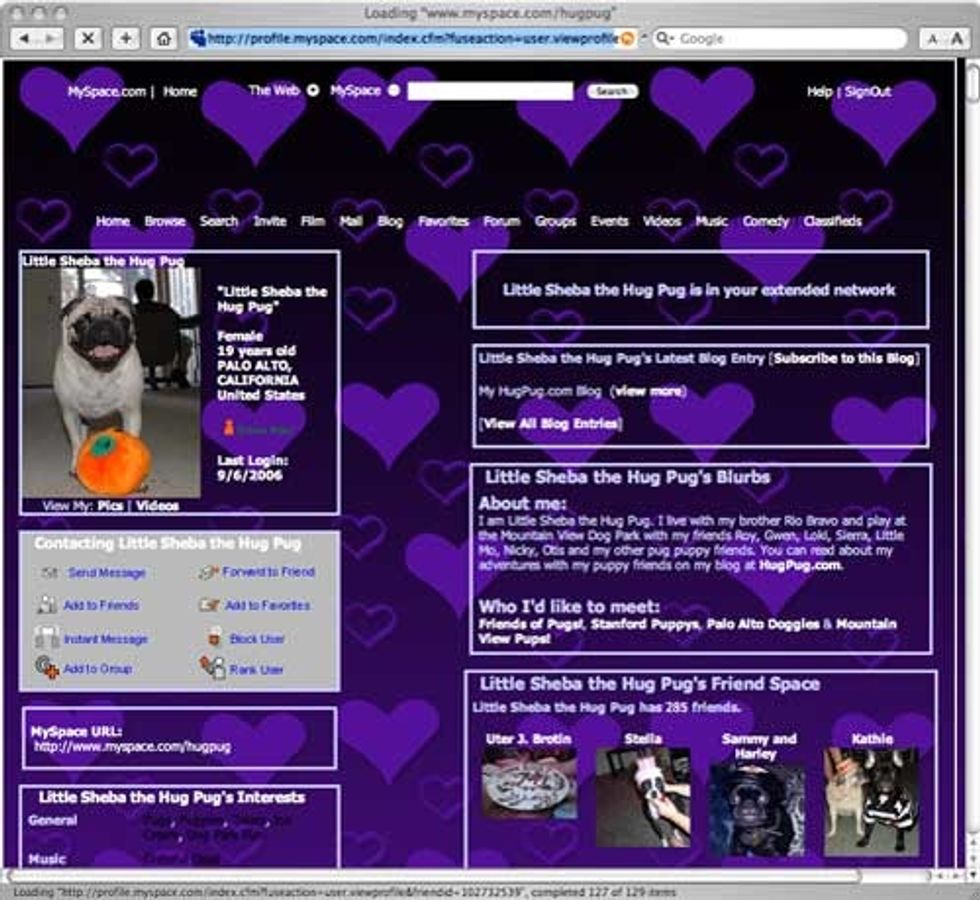

Myspace, on the other hand, felt like pure chaos. Alongside slots for personal information, users could customize their entire profile, from background and text colors to music. There were even ways to change the mouse effects on your page, so that whenever anyone came to your profile their arrow would shoot dumb purple sparkles.

Browsing through Myspace profiles oftentimes felt like exploring a museum full of oddities, except instead of strange artifacts these were manifestations of people’s personalities in full display. There were indie musical artists, scene kids with wild hair, and endless streams of text-covered photos. If you saw someone you liked, you could even send a friend request.

Most importantly, Myspace had a feature known as “Top 8,” wherein users could organize their Top 8 best friends, in order, to display to the world. Friendships lived and died based on Top 8 rankings, and if you wanted to be anyone’s best friend material, you needed to be on Myspace. For middle and high schoolers in the mid-2000s, this turned Myspace into an essential social scene unlike anywhere else on the Internet before or since.

In a Vice article titled “Myspace Wasn’t a Simpler Time, We Were Just Teenagers,” author Samantha Cole responds to a recent wave of millennial Myspace nostalgia on Twitter: “As today’s trending tweets about Myspace show, we like to paint the past in broad, optimistic strokes. The reality is, Myspace wasn’t what we would call ‘evil’ today…But it wasn’t innocent, either.”

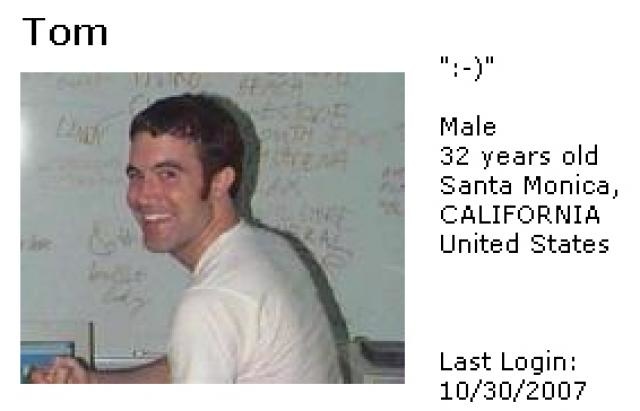

Indeed, a good portion of Myspace nostalgia seems to center around the idea of Myspace being a more moral form of social media than something like Facebook that notoriously turns user data into a massive source of profit. In these posts, Tom Anderson—everyone’s first default Myspace friend and the site’s co-founder, perhaps best known as “Myspace Tom”—is presented as a far purer breed of tech mogul than someone power-hungry like Mark Zuckerberg.

Remember Tom? Remember how he just sold his $500m share in myspace and retired so he could have a nice life? He nev… https://t.co/utFAepHjjQ— ᴊᴀᴄᴋ 👑 ✨ (@ᴊᴀᴄᴋ 👑 ✨) 1594654403.0

Cole points out that this perception of Myspace’s morality isn’t entirely accurate, as, on top of some Myspace engineers getting caught using backend tools to spy on women, Myspace Tom’s $520 million dollar sale to media mogul Rupert Murdoch all but guaranteed that user data would be sold to the highest bidder. And in making that deal, and largely paving the way for future companies like Facebook to do what they do, can Myspace Tom really be considered ethical?

I’m not entirely sure. But even if Myspace Tom is just as morally corrupt as Mark Zuckerberg, I fundamentally disagree with the assertion that Myspace nostalgia is simply the result of rose-colored glasses.

Myspace wasn’t the last good social media because of its ethics, or because it came during “a simpler time.” Rather, it’s because Myspace was the last form of social media to preserve that wanton sense of individuality and discovery that pervaded the early Internet.

Before sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit became the major hubs of online communities, the Internet had a vibe similar to a virtual Wild West. If you wanted to look up, say, Final Fantasy VII, you couldn’t just look up a dedicated FF7 forum with 46,000+ subscribers. Instead, you’d go to a personal site hosted on Angelfire or GeoCities, where one lunatic dedicated countless hours to compiling information, images, and sprites of side character Vincent Valentine and covered half of it in rainbow text fan-fiction.

If anything, the Internet was a lot less “simple” than it is now, and it wasn’t all rosy. Trolls always thrived under the anonymity granted by niche forums. But it was much more exciting. People hosted their weird personal web pages not because they wanted to sell you products, but because they were genuinely passionate about something. Entire websites were drenched in the personalities of their creators, and communities felt small and niche enough to the point where you felt like the other people you were communicating with really were individual people.

Myspace was the last social media that recognized the Internet’s unique potential for individuality. It condensed the experience of traversing the bizarre webscape of GeoCities domains into a single social media experience whereby profiles reflected something deeper about their owners’ personalities than a simple list of interests.

When Facebook blew up in the late 2000s, it offered a fresh start to social media for a more mature you. By then, your Myspace profile was undoubtedly full of your most embarrassing adolescent antics, and Facebook wanted to treat you like an adult. It offered sleek, uniform profiles and the chance to express your interests without going over-the-top. After all, being an adult is oftentimes about conforming to the standards that society thrusts upon you. Shouldn’t your online presence reflect that, too?

Since then, social media has followed along those same trend-lines indicative of “maturity,” growing ever sleeker, ever sparser and, most importantly, ever more similar. Why dedicate a profile to paragraphs of text when you can get a message across in 280 characters on Twitter? Even better, on Instagram you can express yourself entirely through images. No words required except hashtags, of course, because how else could you find 8,000 similarly photoshopped pictures of the same white sand beach or curated kitchen? With our newfound maturity, we’ve outgrown the impetus to be unique.

Thus, Myspace died as the Internet’s primary hub for social media, and D for Dandetta died alongside it. Perhaps whoever you used to be died, too, but maybe that was for the better. Maybe.