Autism isn’t a superpower, but good luck telling that to Hollywood.

For people who fall on the spectrum, autism tends to be a complicated aspect of identity. Autistic experiences differ in just as many ways as the experiences of any other diverse group, and individuals with autism are precisely that—individuals. In movies and television, however, autistic people are depicted in shorthand.

In the past, autistic people were almost always portrayed as helpless in all aspects of their existence, often possessing savant-like genius in one specific area (usually related to math or science). This trend transcended genre, from serious dramatic works like Rain Man to horror schlock like Cube.

While mostly inaccurate and incredibly flawed, the autistic savant trend has recently given way to something potentially more damaging: autistic fetishization. This modern trend portrays autism as cool and desirable, a primer for superhuman abilities or even the next step in human evolution. That’s not to say autism can’t be cool or desirable, especially when defined that way by people who live with it daily, but a problem arises when the voices defining autism in pop culture don’t have autism in the first place. The result is a series of Hollywood-generated “autistic archetypes” that never entirely ring true to the experiences of actual autistic people.

The Autistic Savant

Raymond Babbit from Rain Manwww.asset1.net

Raymond Babbit from Rain Manwww.asset1.net

For many people in the late 80s, Rain Man was their first encounter with autism. The movie follows Charlie Babbit, a narcissistic car dealer played by Tom Cruise who discovers that his deceased father’s fortune has been left to his older brother, Raymond (Dustin Hoffman), an autistic savant with the ability to calculate numbers at an alarming speed. So Charlie kidnaps Raymond from his mental institution to take him on a cross-country road trip back to Los Angeles to gain access to the money.

When it came out, Rain Man was considered a great movie – it won the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay. Dustin Hoffman also won Best Actor for his portrayal of Raymond Babbit. All things considered, at a time when autism had almost zero representation anywhere, Rain Man at least provided a sympathetic introduction.

That being said, Rain Man inaccurately shaped the public perception around autism, resulting in a long-standing conflation of autism with savant syndrome. While savant syndrome – the condition in which a disabled person displays greater than average abilities in particular areas – is related to autism, it is in no way conventional. Less than one in ten autistic people display any sign of savant syndrome at all, and of those, very few possess extraordinary abilities.

Moreover, Hoffman’s depiction of Raymond instilled the impression that autistic people are largely incapable of functioning on their own. And while that’s the case for some autistic people, many others are fully functional in their daily lives and are able to live alone, work regular jobs, and care for themselves.

But looking back, Rain Man‘s biggest failing was the fact that Raymond Babbit wasn’t a character in his own right. While Hoffman certainly put on a great performance, one never got the sense that Raymond had hopes and dreams and thoughts beyond the scope of his “autistic” rituals and traits. The character existed primarily as a force for changing Charlie, the movie’s true protagonist, as opposed to functioning in any standalone capacity.

Of course, it was never Rain Man‘s job to inform the entire public on such a complex subject as autism. In a limited scope, the movie didn’t do a horrible job bringing one individual autistic savant to the screen. Unfortunately, given the movie’s success, its limited perspective had far-reaching effects on the broader perception of autism, with watered-down “autistic savants” and “low-functioning autistics” becoming a form of Hollywood stock character for decades to come.

The Autistic Goofball

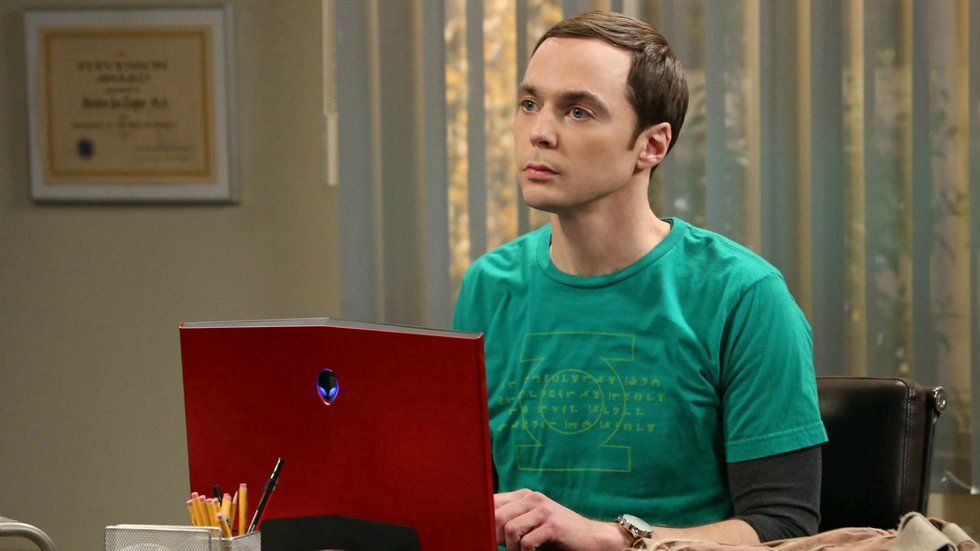

Sheldon from The Big Bang Theorywwwimage-secure.cbsstatic.com

Sheldon from The Big Bang Theorywwwimage-secure.cbsstatic.com

Then, in 2007, The Big Bang Theory aired on CBS, bringing with it the character Sheldon Cooper and a whole slew of new stereotypes.

In a sense, Sheldon represented an evolved form of the autistic savant trope. His savant nature, as usual, manifested through expertise in science. But his autism was different. Unlike almost every other “autistic” character formerly represented on screen, Sheldon was fully self-sufficient. He was capable of living on his own, taking care of himself, and holding a job in his profession of choice. Rather, Sheldon’s autism was expressed entirely through social ineptitude.

To be clear, the creators of the The Big Bang Theory denied that Sheldon had autism, and the actor who played him, Jim Parsons, stated that he didn’t intentionally play Sheldon as autistic. There’s also a strong argument to be made that the entire main cast of The Big Bang Theory, which is about a nerdy friend group who all work as scientists, probably fall somewhere on the spectrum based on their behaviors throughout the series.

But regardless of what was intended, Sheldon absolutely read as autistic, especially to people who fall on the more high-functioning end of the autism spectrum. He had trouble understanding the feelings and emotions of others, struggled with properly conveying tone and self-censorship for the sake of politeness, and skewed towards obsessive-compulsive behavior. Considering The Big Bang Theory was a mainstream sitcom, all of these traits were dialed up to 11 for laughs.

In some ways, Sheldon’s representation on The Big Bang Theory was positive for the autism community. For one, Sheldon was the first “autistic” character who felt like an individual, albeit an incredibly unrealistic one. Parsons imbued the character with a sense of personhood that went beyond his autistic “traits.” Also, as the show progressed, Sheldon grew and changed as a character, eventually developing and navigating a romantic relationship that would have seemed impossible for him when the show began.

Still, Sheldon’s portrayal on the The Big Bang Theory is largely negative, and most of the show’s jokes come at his expense. His antics, almost all of which would be chalked up to his neuroatypicality if the showrunners recognized its presence, are viewed as weird and funny and quirky – which isn’t to say that autistic traits can’t be all of those things, especially when viewed in that light by the people who are genuinely neurologically atypical. But there’s a difference between someone saying, “my brain is weird and I like it that way” and pointing and laughing at a character who displays amplified versions of those traits – because for people with autism, many of those quirky, weird, funny traits also have very real downsides.

Moreover, due to the fact that Jim Parsons is neurotypical, his exaggerated performance of clearly autistic traits for laughs comes off as a sort of “autism blackface.” The Big Bang Theory is largely content with poking fun at autistic people without ever accounting for their real-world struggles, all without taking any of the social responsibility by calling that condition what it is.

The Autistic Superhuman

Rory from The Predatorstatic3.srcdn.com

Rory from The Predatorstatic3.srcdn.com

While the functional-but-hilariously-inept autistic trope has become more and more common since The Big Bang Theory, a new trope has also recently started to emerge – the autistic superhuman. This new archetype submits that autistic people (almost always savants, of course) are prime targets for fetishization due to their unnaturally high intelligence and skills.

For instance, the 2018 Ben Affleck movie, The Accountant, sees Affleck portraying an autistic mathematics savant named Chris who works as both an accountant and a highly-trained assassin. But don’t worry, his autism is ever-present, as he exposes himself to loud music and flashing lights on a daily basis to overcome his issues with sensory overload, and recites nursery rhymes to himself while killing people.

It’s not a terrible movie in terms of enjoyably bad action fare, but its presentation of autism is dangerous. The suggestion that an autistic person could overcome sensory overload by essentially torturing himself is ludicrous. The recitation of nursery rhymes during acts of violence is frankly just silly.

Overall though, the notion of an autistic savant whose savantism centers on assassinations (but math too, obviously) comes off as a weird sort of fetishization, especially when none of the writers or actors involved are autistic. It seems to say, “imagine how good you’d be at martial arts if you were a savant, wouldn’t that be cool?”

And sure, maybe it would be. But our broader cultural understanding of autism isn’t at a point where fetishizing it is helpful, especially when actual autistic people face barriers to entry in all sorts of professional fields, let alone underground crime networks.

Still, the most egregious example of the autistic superhuman is, without a doubt, 2018’s The Predator. This installment finds its alien antagonist hunting for a top human specimen to take into space in order to fuse with its DNA or something. You’re lead to believe the Predator is coming after the protagonist, a buff Army Ranger named Quinn McKenna. But nope, the movie’s biggest twist is that the Predator is actually after McKenna’s autistic savant son, Rory, because autism represents an advancement in the human genome. Yes, the movie actually states this. Which, if true, begs the question: why did the Predator choose to hunt an autistic child in 2018 as opposed to any other autistic person at any other point in human history.

But okay, sure, we get it. Autism isn’t just desirable in Hollywood anymore. It’s desirable in outer space too.

Again, all of this would be fine if it were coming from autistic people as a reflection of their real-world experiences. Except it’s not. Hollywood wants autistic characters, but they don’t seem to want autistic people. Autism is desirable to them in concept, but not in reality.

The “Realistic” Autistic

Sam from Atypicals3.r29static.com

Sam from Atypicals3.r29static.com

Some shows do make a more honest effort to hold their portrayals of autism to a higher standard. While not without its flaws, Netflix’s Atypical offers one of the first Hollywood depictions of an autistic character who can both function on his own and is not a savant. The protagonist, Sam Gardner, is for all intents and purposes just a typical high school student who happens to be neurologically atypical. The show focuses on his social struggles, love life, and family relationships. It shows many of the more humorous sides of autism while never making Sam the butt of the jokes, but also attempts to explore the more frustrating elements of living with autism.

Unfortunately, this is the area where Atypical flounders. In the real world, most autistic people on all levels of the spectrum only display certain traits associated with autism. For instance, trouble holding eye contact, hand flapping, obsession with a certain subject, rocking back-and-forth when stressed, and aversion to certain foods can all be signs of autism, but a single autistic individual is unlikely to display every single one of them. Real autistic people also display the traits they do have with a high degree of consistency.

Sam, on the other hand, feels less like a real person and more like a checklist – he displays almost every trait commonly associated with autism, but the worst of it (i.e.: outbursts related to noise) seems reserved for convenient plot points as opposed to whenever Sam is surrounded by too much noise.

These issues are compounded by the fact that not a single writer, director, or producer on Atypical actually has autism. And while the show made efforts to hire five autistic actors to play the members of an autism support group at Sam’s school, it begs the question of why they didn’t hire an autistic actor to play Sam. After all, the show proves that autistic actors are out there in Hollywood, actively looking for work. Which leads to a much greater point.

The Future of Autistic Representation

Currently, diverse representation seems to be a hot button topic in Hollywood. From women and LGBTQ people to ethnic and racial minorities, Hollywood has been making significant strides over the past few years to open the proverbial gates to distinct voices from all walks of life. Diversity programs helmed by almost every major studio seek out fresh writers and directors for hands-on training. And yet when it comes to autism, the gates seem all but closed.

The notion of a television show about a black character with an all-white writing team or a female character with an all-male writing team would be insane in this day and age. And yet when it comes to a television show about an autistic character, a fully neurotypical writing/directorial team is all but guaranteed. Even worse, they’re still trying to highlight diversity amongst their staff. In 2018, Variety released an interview with David Renaud, a wheelchair-bound writer for The Good Doctor, who said: “The story is about autism, but in my mind, it’s a story about a disabled character. Autistic, blind, deaf, wheelchair-users — we’re all part of this big community of people who are struggling to have our stories told. And not just told, but told in an authentic way.”

While it’s great that Renaud is leading the career he wants in spite of his physical disability, his interview is incredibly problematic, as he seems to misunderstand autism fundamentally. Autism is a neurological atypicality, not a physical disability. Grouping autism and being in a wheelchair within the same “disabled” category is like grouping cis white women with transgender people because both have faced “discrimination.” In fact, many people within the autism community do not consider themselves disabled in the first place, viewing their autism with pride as an intrinsic part of their identities. But of course, these are the subtleties and distinctions that neurotypical people “studying” autism to write fictional characters are likely to miss.

Similarly, a white person playing a black person in a movie would instantly get called out for blackface. Even if the stigma of sociopolitical sensibilities wasn’t a concern, a white actor couldn’t possibly portray a black character’s experience more authentically than a black actor could. But when a neurotypical person plays up autism for laughs, they win Emmys. Outside of the autism community, nobody seems to mind.

All this would be understandable if there weren’t writers and directors and actors on the spectrum, actively looking to break into the industry and make a name for themselves. But there are. There are many, each with authentic perspectives on the autistic experience that go far beyond a neurotypical person doing “research.” It’s no wonder that despite the growing number of autistic characters hitting the big screen in recent years, actual autistic people still don’t feel represented.

The issue Hollywood doesn’t seem to understand is that autism representation isn’t just about showing a character on screen and calling them autistic. It’s about giving autistic creatives the opportunity to bring their authentic voices to the screen – same as any other minority. It’s time for autistic people to be included in diversity programs. It’s time for autistic characters to be written by autistic writers and played by autistic actors. It’s time for us to tell our own stories.