Andrew Callaghan Interviews the Most Controversial People in America on 'All Gas No Brakes'

Neo Nazi's, Furries, Flat Earthers, UFO Hunters, for Andrew Callaghan they all got something to say

Update 4/15/2021: After announcing in March that they had parted ways with former backers Doing Things Media — over contract disputes and disagreements about the political nature of their content — the All Gas No Brakes crew have returned as Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan.

Having lost access to their old content and revenue streams, the team are hoping to rebuild, and have just dropped their first video on the new channel, delving into this year's spring break chaos in Miami Beach, Florida.

Miami Beach Spring Breakwww.youtube.com

Andrew Callaghan has always been drawn to the absurd.

Born and raised in Seattle, the budding Internet star and host of the web series All Gas No Brakes described himself as a mischievous teenager. A "fourteen-year-old stoner" who divided his time between "anarchists and hip-hop kids," he regularly found himself surrounded by unsavory characters.

During his freshman year of high school, Callaghan enrolled in a journalism class, and his teacher actively encouraged him to write on the seedy lifestyle he experienced.

"I was already getting myself into weird, sketchy shit for my own enjoyment," Callaghan told me. "So being able to have a platform to share those experiences was like the ultimate gratification."

Callaghan wrote investigative op-eds on how to access the Deep Web and described how to buy drugs off the now-defunct Silk Road. He talked first-hand about life inside Seattle's tent city during the Occupy movement and about his experiences hanging out with Juggalos in Seattle's sleazy Westlake Center. His classmates and his teacher were fascinated.

Callaghan, who travels around the country in a beat-up RV and interviews people, has somehow made a career out of meeting America's strangest characters. Trump supporters, Flat Earthers, Furries, UFO Hunters ––he's even met Diplo.

While Callaghan regularly hears and sees abhorrent things on the road, he has an uncanny ability to remain completely unfazed. He often lulls his subjects into a false sense of security.

"I call it hyper-agreement," he said. "Just don't be a dick, and validate your interviewee with aggressive head nods and inquisitive facial expressions." It's a similar tactic to what you might see on "The Daily Show" with their 'man on the street' segments.

During the tense Anti-Antifa rally in Portland, Oregon, last summer, Callaghan became partially embroiled in an absolutely ludicrous standoff between a white supremacist and an Antifa supporter. "[Antifa] needs to go the hell away," said Callaghan's interviewee. "We need to go the hell away from our city?" called out a bystander on his bicycle, "F*ck you." As the two squared off, Callaghan documented it all, his microphone seen in the corner of the screen.

Even when things go off the rails, Callaghan somehow remains fearless. "You just can't convince certain people of certain things, especially when they believe that public information is controlled by nefarious puppet masters," he said. "Things often go wrong afterward. I've gotten a handful of lawsuit threats...frat bros try to fight me."

In fact, it's in the quieter moments that Callaghan struggles to keep his composure. At the 2019 Flat Earth Conference in Dallas, Texas, three separate Flat Earthers justified their beliefs by quoting Protocols of the Elders of Zion a propaganda book used by Hitler in the 1930s to sway public opinion against the Jewish people.

"I had a hard time holding my tongue," he admits.

While All Gas No Brakes is still in its early stages (he recently asked his fans for donations so he could start to put together a production team), Callaghan has amassed years of experience interviewing off-putting characters. At nineteen, Callaghan hitchhiked across the country for 70 days completely alone.

"After I took my last final, I basically sprinted out of campus," he told Office Magazine. "I left everything in my dorm, all of my stuff...I just didn't even think about it."

When his adventure ended, he composed an online zine, fittingly titled All Gas No Brakes, where he wrote on a few of his most noteworthy encounters.

From there, he wound up working as a doorman on New Orleans' infamous Bourbon Street. "I always thought of Bourbon Street as the last frontier of anarchy in the western world," he told Office. "It's this backward city of corrupt institutions. People come here from all across the world and they get possessed by this spirit...you're truly able to see what humans are like in their raw form."

One day, he abruptly quit his job and decided to document what he was seeing in a "smart and funny way." He became the anchor of "Quarter Confessions," a relatively popular Instagram and YouTube channel that documents drunk people on Bourbon Street. "Sometimes I miss the consistent, chaotic simplicity of Bourbon Street," Callaghan told me. "But [the yelling] got old."

As All Gas No Brakes has gained traction. The show has garnered the attention of a few notable celebrities, such as millionaire playboy Dan Bilzerian. "He's a fan and a mega-tool," Callaghan said of the infamous poker player.

The two were scheduled to meet up while Callaghan was filming in Las Vegas. Bilzerian thought it'd be fun to crash a party together. "[He] flaked at the eleventh hour with a text that read, 'sorry bro, I think I'm gonna smoke and bang these girls,'" Callaghan said.

"I could roast him further, but that's enough said. Dude's corny, take my word for it."

As the show has grown, Callaghan has somehow managed to turn a handful of his subjects into reoccurring characters, almost like it's a sitcom. On his most recent trip to Las Vegas, he hit the strip with Mr. Daddy and Luchi, two strange men he had met on two separate occasions a few months prior.

"I like the idea of recurring characters," he said. "Plus [they] embody two staunchly different but equally essential Vegas character types–the unstoppable coke dive and the aspiring promoter who whispers sweet dreams of exotic cars, Versace robes and 7 to 1 gender ratios [at parties.]"

Moments like this are everything to Callaghan. "Every day is a new adventure and because of the show, I have friends everywhere." While his passion project is only just starting to take off, Callaghan already has enough stories to fill a memoir. He's seen Juggalos pee on each other's heads at Mike Busey's Sausage Castle in Orlando, Florida.

He interviewed Kimberly Guilfoyle at Donald Trump Jr's book signing, as well as a woman who referred to the LGBTQ community as "witches" and proudly believed that people should only date within their race.

"Just today I crashed the press conference at the AVN awards, where I asked [adult film star] Alexis Texas if she's ever worried she won't get gifts at Christmas if her family sees she's been naughty."

He hopes to one day see All Gas No Brakes become its own "gonzo" journalism show, but for now, he's just focused on interviewing a man named Daryll. "[He] believes he's an alien named Bashar."

Follow All Gas No Brakes On Instagram, YouTube and Patreon

- Famous Rappers' Net Worth - Popdust ›

- Interview: Luh Kel Was Made For This Moment - Popdust ›

- 6 Controversial Metal Bands Banned Around The World - Popdust ›

- 6 Important LGBTQ Metal Icons - Popdust ›

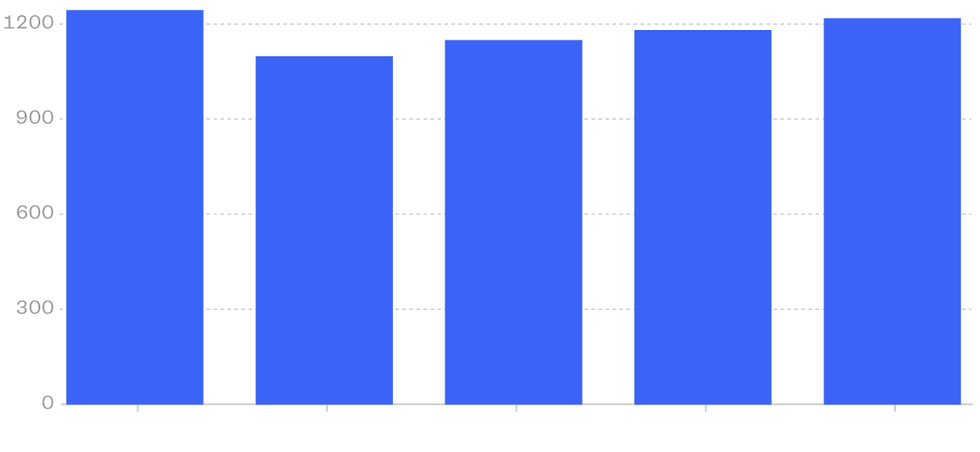

NOTE: Includes hate crimes against gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, gender non-conforming and mixed group victimsSource: FBI, Chart: Nigel Chiwaya at NBC News

NOTE: Includes hate crimes against gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, gender non-conforming and mixed group victimsSource: FBI, Chart: Nigel Chiwaya at NBC News

If You Think "Karen" Is a Slur, Then You're Definitely a Karen

A brief history of "Karens" and how to spot them at your local Women's March.

Whether you know someone actually named Karen or not, there's a high possibility that you've met a "Karen."

Not all "Karens" are named Karen, and not everyone named Karen is a "Karen"—but "Karens" are constantly walking (and tweeting) among us. Not too far removed from the "can I speak to your manager?" meme before it, "Karen" has become a catch-all name for the type of white woman with whom we've unfortunately grown all-too familiar. "Karens" live with the idea that their womanhood exonerates them from white privilege, and their day-to-day shenanigans prove they truly don't know how to read the room.

If you're so lucky as to not have dealt with a Karen in real life, then you've probably read about them in stories online. The woman in Oakland who called the police on a black family for barbecuing by the lake? She's a Karen. That time "gun girl" Kaitlyn Bennett said "we don't live in a racist society"? She was being especially Karen-like. Just this week, when Alyssa Milano—starter of the #MeToo movement—said she was continuing to endorse Joe Biden, without acknowledging the sexual assault allegations against him? Peak Karen behavior.

But the most Karen of all Karens is writer Julie Bindel, who tweeted some absolute insanity over the weekend: "Does anyone else think the 'Karen' slur is woman hating and based on class prejudice?" Ah, yes—good ol' class prejudice against upper-middle-class white folks. What could be more nefarious?

As with a lot of slang that's been adopted by the masses over the past decade, this usage of "Karen" was first coined by black people. It's since become canonized in reference to women like Bindel, who are so caught up in their narrow, self-centered view of feminism that they fail to acknowledge their glaring white privilege.

Most of all, Karens don't want to be left out of anything—especially oppression. They will latch onto any inconvenience that gives them the tiniest semblance of systematic oppression, arguing that "Karen" generalizes a specific collection of traits—white, middle-aged, upper-middle-class—as if those aren't the exact traits most frequently found in men of power. What makes Karens so dangerous is that they claim to be feminists but only act on it when that feminism directly benefits them; their racism, homophobia, and transphobia aren't always explicit, but their actions lack all the nuance of intersectionality.

Worst of all, Bindel's tweet seems to liken "Karen" with racial slurs, as if "the K-word" could ever come close to approximating the malicious history of actual derogatory words (plus, FYI, there already is another "k-word").

In summary: Don't be a Karen. "Karen" isn't a slur. If you're innocent and your name just so happens to be Karen, I'm so terribly sorry.